THE EYING OF MY SCARS

by Tony Wilkes | February 8, 2018

“Collection of Sylvia Plath’s possessions to be sold at auction” reads Tuesday’s Guardian. Up for grabs are the proof copy of Plath’s novel The Bell Jar (1963) and her pre-publication author’s copy. Both are written on: her proof edition is “carefully corrected”, and her author’s copy “inscribed with the date Christmas 1962, and the address Fitzroy Road”. They are expected to fetch for £60,000 and £80,000 at Bonhams in March 2018.

The news of auction comes just four months after the publication of Faber & Faber’s complete and unabridged Letters of Sylvia Plath Volume 1: 1940-1956. As the two editors explain in the ‘Introduction’, the book “present[s] a historically accurate text of all the known, existing letters” written by Plath. Both the editors and auctioneers are seemingly united in a common goal. The senior book specialist at Bonhams says that “the core of the collection is the words and the work”. For the editors, the letters “reveal…the genesis of many poems, short stories and novels”. So her belongings and her letters are sold and published for the benefit of her art – or so we are told.

When we read the ‘Introduction’, and the ‘Forward’ – written by Plath’s daughter Frieda – it’s apparent that the book doesn’t set out to illuminate the work, but to illuminate the author herself. The aim is not to shed light on her life but to bring her back to life. Frieda writes, “through publication of her poems, prose, diaries, and now her collected letters, my mother continues to exist”. The letters become a way to hear the dead speak, for Plath to “narrate her own autobiography” with limited interference. The “transcriptions…are as faithful to the author’s originals as possible”. Irregularities in spelling, punctuation, grammar – even errors – are “faithfully transcribed…without editorial comment”. The book is not so much a collection of letters, but a recording of an untainted voice, a means by which to relive “her experience” – to resurrect the dead.

In so doing, the book helps thicken Plath’s history into myth. In reconstructing her life – be that through her writing or her possessions – we are fuelling what can be best described as Plath’s ‘literary martyrdom.’ You don’t need to have read Plath to know end of the story: the woman amidst the ruins of her marriage on the brink of suicide, “writing the best poems of my life”, those that “will make my name.” The story of how she blocked up the door to the bedroom of her two toddlers and gassed herself, her head in the oven. But why has her suicide created a martyr? Partly because the poetry itself pre-emptively mythologises the reality. Plath uses poetry to transform herself into a seething, exhilarating modern Medea who transcends death in the act of escape. In ‘Ariel’, she catapults out of her maddening enclosure into the violent freedom of the sky as “the arrow,/The dew that flies/Suicidal, at one with the drive/Into the red eye, the cauldron of morning”. So arguably, it’s not readers that have created the “Plath Myth”. Her escape through poetry has emblazoned the head in the oven onto our cultural psyche.

The fact that Plath uses poetry to escape demonstrates her faith in the power of her craft, especially as a confessional poet. So just as a Christian is martyred for their enduring faith in God, it could be said that the literary world has martyred Plath for her enduring faith in literature. The difference perhaps is that Plath didn’t die to cultivate a religious following, but nevertheless her death has been made into something of a martyrdom cult. Her poetry anticipated this martyrdom. In ‘Lady Lazarus’ she writes: “there is a charge, a very large charge/For a word or a touch/Or a bit of blood/Or a piece of my hair or my clothes”. As The Guardian reports, her “clothes” are going on sale; pieces of her life are being distributed amongst Plath addicts. Even her grave has a dedicated page on ‘Trip Advisor’, to direct fans making the pilgrimage, who will leave tributes – pens with handwritten notes. A tribute to her writing.

The editors’ process shows just how far this worship has come. What happens when the work and the author seep into each other – when the work transforms a person into myth? Is everything Plath wrote and said, everything she left behind, to be included in her work? A line ought to be drawn but the editors of The Letters refuse to do so. Every surviving letter written by Plath is included, compiled into a 1,330-page brick. The Letters do not engage with Plath’s work, but seek to reconstruct her. And to do so is to meticulously catalogue her very existence.

So it comes as no surprise that much of these letters are dry. Reading through 1943 is excruciatingly dull, since 11-year-old Plath isn’t a poet. She’s a child. But the meticulous transcription proves rather sinister. We read of exactly what she’s eating: “2 bowls of vegetable soup, 2 cups of milk, 1 orange & 1 peanut-butter sandwich.” We know exactly what she’s spent: “45c on laundry about 20c on fruit, 1.50 on nessities and 20c on unnessities. About 2.40 in all” To top it all, we read of her “ingrown toe-nail”. This hunger for detail operates on the level of the notes as well. Rather than “bring[ing] context to Plath’s life”, the annotations serve to direct us to further relics, such as the exact location of her essays. We can only thank God they can’t find her receipts, her shopping lists.

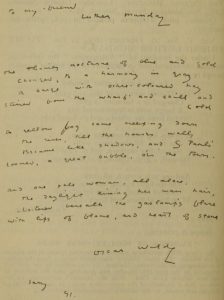

The book is still oddly enjoyable. I’ve continued to read it. Immersed in the banality of Plath’s life, we can trace our own experience through hers. This being my second term at Oxford, reading her letters from her first “semester” at Smith College raises a warm satisfaction from common experience. My fresh optimism echoes her own – “When I get used to the routine, I’ll no doubt be more rested” – as well as her experience of freshers’ flu: “Everybody in the house has colds. Coughing and sneezing echoes down the halls.” We also find those ‘I’m-writing-what-I’m-feeling’ moments throughout her Journals. In a letter from 24 October 1950, “Smith” could easily be replaced with “Oxford”:

“Am I queer, or is it normal that I am so snowed by being a microcosm here that I don’t yet get the feeling of going to Smith? It’s hard to explain, but I don’t find myself able to pull away & evaluate my self in relation to my surroundings.”

Because of this constant cataloging, we can reference our own lives against Plath’s. We can indulge in the similarities. Sandra M. Gilbert begins her article – “Confessions of a Plath Addict” – by “trac[ing] our own journey through hers”. Four years after Plath, Gilbert held the same position as Guest Editor of Mademoiselle magazine, a position which Plath recounts in The Bell Jar. And in some ridiculous respects, I can too. I’ve been accepted to Oxbridge, I’m writing, I’m contributing to The Isis magazine. Those who read Plath can now somehow place themselves along her timeline. And the Letters play into this. The footnotes don’t really orientate us within Plath’s life – they provide intricate details to a kind of plot:

Cast members: “Elizabeth (‘Betsy’) Whittemore MacArthur (1933- ); B.A. 1954, botany, Smith College, SP’s housemate at Haven House”. Settings: “Wiggins Tavern, in the Hotel Northamption, 36 King Street, Northamption, Mass”. Events: “A Streetcar Named Desire was performed at the Academy of Music, Northampton, Mass., at 8:30pm”.

The footnotes provide the details needed to figuratively re-trace Plath’s steps. But the only reason this proves so fascinating is because these experiences are Sylvia Plath’s. We are encouraged to revel in her experience because it is handed down to us from some mythic high-alter. We walk in the shoes of a saint.

It would be unfair to condemn The Letters as a deadening embalmment of a life. The book contains glimpses of Plath’s creative and poetic talent, with an occasional “snatch of verse.” Lines describing “giddy whirls/And sweeps of fancy/Sunlit leaves plane down/Lisping along the street” are welcome bursts of life amidst the “faithfully transcribed” mundanity. But it is ridiculous to consider The Letters of Sylvia Plath as a valid contribution to her work. Instead, the book offers yet another angle to the same story, the same well known myth. So to use a phrase from Plath’s poetry, the readers can “poke and stir”, but unfortunately, “there is nothing [much] there”.

Artwork by Isabelle Davies