In Praise of Letters

by Maya Little | September 15, 2018

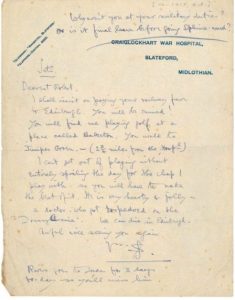

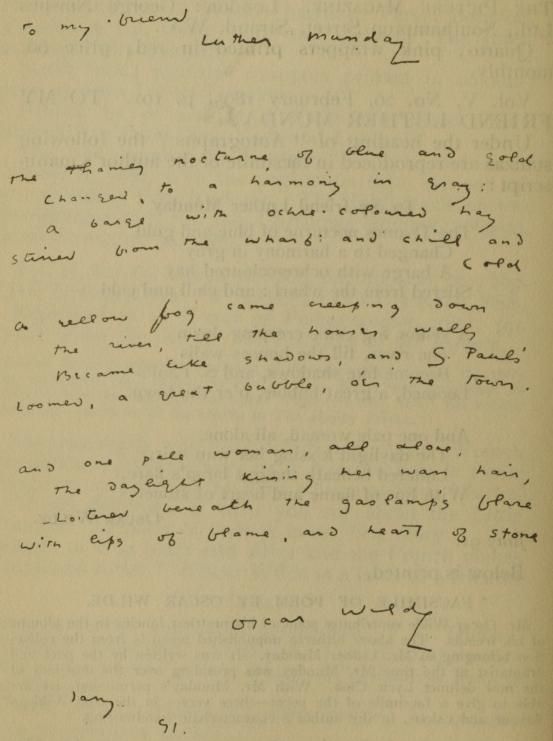

Letters have always seemed a strangely heightened form of communication to me – you can’t burn an email, and frankly, I’ve yet to see an email worth burning. Letter writers from Oscar Wilde to Peter Wildeblood have found themselves incriminated by their own words. Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf have had their letters published for posterity, nothing apparently too personal, even their suicide notes.

The letters I write are hardly worth publishing but writing them nonetheless has a feeling of permanence. Letters have become for me a kind of promise, a way to make communication purposeful, rather than off hand, like a Facebook message, or obligatory, like the reply. I would feel guilty if I threw a letter away after reading it only once – this defiant act of crossing distances, this invitation by someone else to voice their words, just for myself. I always find people’s voices in letters slightly contradictory, the writer performing themselves for me, and yet being unable to escape from themselves as they write.

My mother’s voice in her letters echoes her voice when we speak, flowing from one thing to another, lively. My father’s voice feels mediated, effortful, and I appreciate this just as much. There’s some distant-past recollection of his grammar school days in his letters: the ‘I am’, rather than ‘I’m’, the neater hand writing. It’s still his voice, but he has thought and deliberated about how to speak with me, and his words are covered in a residual formality that is somehow endearing. Sometimes, like the radical 60’s kid he is, he’ll break from form, write a few words in block capitals, make a list, add a drawing.

In the holidays, friends write, and as a generation for whom writing letters is foreign, there is a slight excitement in the pretension of what we’re doing, another level of unnaturalness that is not there in the letters of my mother, who wrote prolifically and excitedly to her own parents. For some of my friends, this feels very new, the occasional childhood letter to friends who moved away long since replaced with the slightly creepy peripheral awareness of each other’s lives through social media. We exchange elegant sentences, and carefully allow truths to slip in, having the time to let ourselves do it. It is easier to be kind in a letter, perhaps because it is implicit in our culture that to put something in writing is to really mean it. It’s easier to be truthful, too, when the most immediate of reactions will take several days from the moment of writing, so that the emotional impact of what you are saying will be diffused across a stretch of time, becoming more manageable.

The letter is so personal because the writer cannot get themselves out of it, as they could in a quick message or text. It is difficult to avoid something by stopping when you get to it; the jump to the next thing, even to ‘Love,’ will be perceptible. Further, the reader would know if it was not your handwriting. To shorthand feelings with ‘lol’ or ‘<3’ is unacceptable. The writer chooses how they wish to give themselves with every pen stroke, but they must ultimately give themselves, be it in one long ream of words strung across the length of their being, or as a collection of fragments, desperately hoping that the reader will not be able to piece them together.

All this can make letter writing sound like a very serious business, and it would be wrong of me not to acknowledge the incredible joy of receiving a letter. There is always something unexpected – a postcard of an old advertisement (‘They’re young! They’re in love! They eat lard!’ – yes, really), or a poem. You learn what time the postman comes and are always vaguely disappointed by Sundays. The anticipation of the envelope, white and well-sealed, or cream and taped closed, already carries the writer inscribed upon it, their finger prints invisibly laid under your own. I usually take letters back to my room, read them alone somewhere, afraid to rudely interrupt this little paper voice by getting distracted.

For all the hard truths that people like to slip into letters, there is still this inescapable element of performance – the good letter writer will always select what to write based on what they think the receiver will enjoy. They will exaggerate anecdotes for maximum effect, be comic or thoughtful or newsy depending on the recipient. But this is the most generous kind of performance, tailor made for one audience member, and not written purely for the reader’s enjoyment, or as a display by the writer, but as a gift to the relationship between the two, as maintenance that has taken time.

With the introduction of other forms of communication, from telegraph, to texts, to skype, our conception of the letter’s purpose has shifted away from the purely communicative, and instead towards a justification based on its physicality. With much speedier means of communication about, the letter can no longer be about anything urgent, is rarely about communicating information, and so in order to justify it as a means of communication, we have built a system of values and expectations of content for letters which stem from its physicality. Letters can last, and so they should be beautiful. They are not urgent, and so they can be reflective. They are not informative, and so they should be entertaining. They are handwritten, making them look personal. They are unmediated, except by dead paper, making you feel that you should write personally, that every word you write has an underlying meaning and that meaning is you, you, you, all across the page, in every crossing out, and hidden beneath every crossing out.

The letter has always had the capacity to express both the intensely personal and the extremely witty to an extent that is difficult to achieve in any more fast paced form of communication. But in the modern day, to take time and deliberate as you communicate, and to be willing to wait for a response is not part of the social expectations embedded in any other form of communication, and to write a letter is in itself unusual. It connotes a special occasion, or the relating of an incident or feeling of great importance. But should we not be willing to communicate with the care and attention that is intrinsically required by the letter in all of our valued relationships?

Why do we publish the letters of both the famous and the ordinary alike? Because even the least interesting letter can be disarmingly personal; because they are sometimes the only lasting testaments that we have of love. To write someone a letter is to tell them that they can keep you, in some small way, even if you disappear, even if some day you hate each other – because there was a time when you didn’t. Perhaps it is wrong to publish letters, but to want to read a letter, from a friend, from your mother, from the long dead, is a simple urge: it is the desire to know someone.