Is conscious rap still conscious?

by Lina Osman | December 29, 2024

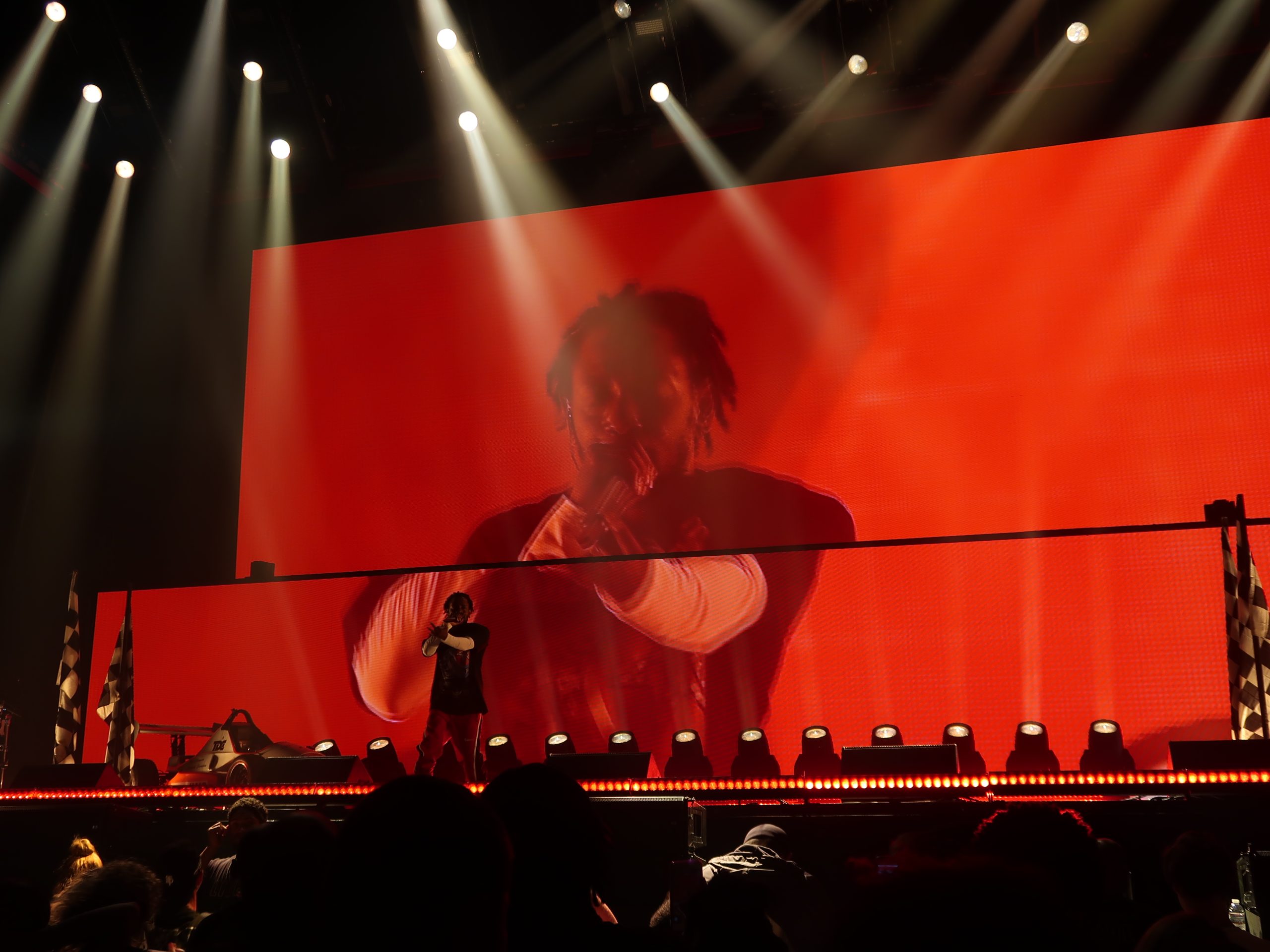

I remember standing in the crowd at Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN. tour, hearing “Alright” live for the first time. The atmosphere was electric: “We gon be alright”. For those few hours, music felt like the most powerful thing in the world—a way to connect, to heal, to resist. Kendrick wasn’t just performing; he was leading.

Fast forward to GNX, Kendrick’s latest album, and I can’t help but wonder if that same spirit is still there. The album dropped without fanfare—no social media campaigns, no enigmatic teasers—just Kendrick casually letting it loose. On the surface, it seemed like a rejection of commercialism. Was it, though? Next February, Kendrick will perform at one of the most commercialised events in the world: the Super Bowl halftime show. The announcement came alongside an ad featuring Kendrick standing in front of an enormous American flag, a callback to the cowboy-style outlaw aesthetic he’s cultivated. The whole thing felt less like rebellion and more like calculated branding, the kind you’d expect from more main-stream artists like Beyoncé or Taylor Swift.

One of the most striking shifts on GNX is how polished it sounds—almost too polished. The basslines on tracks like “squabble up” should rumble with raw energy, but they’re smooth, almost sterile. “luther”, Kendrick’s collaboration with SZA, is sweet and lush, with a gorgeous Luther Vandross sample woven into the orchestral backing. It’s easy to listen to—almost too easy. This is Kendrick at his most sonically palatable, this is Kendrick at his most famous, this is Kendrick without some of the grit that defined his earlier work. Albums like To Pimp a Butterfly and Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers challenged listeners, demanding attention with dense, often uncomfortable production. GNX, by contrast, feels like it’s designed for background play—in the car, at the club. That’s not inherently bad, but it raises questions about whether conscious rap loses the very thing that makes it different: its consciousness, when it’s this polished.

Yet it’s important to remember that Kendrick Lamar’s contributions to music go far beyond one album or one sound. In 2018, he became the first and only artist outside the classical and jazz genres to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music, a recognition that felt revolutionary. The prize was for DAMN., an album that melded searing social critique with deeply personal introspection. The win was a testament to the power of conscious rap, proving that hip-hop could be both commercially viable and artistically profound. GNX begs the question: If Kendrick Lamar isn’t doing conscious rap with a message, what is his role musically? And by extension, can the genre maintain its edge if its figurehead moves away from its core ethos?

This also brings up a broader conversation about the constraints we place on musicians. Is it fair to confine someone like Kendrick to the “conscious rapper” box when other artists are allowed to evolve freely? Taylor Swift can seamlessly transition between country and pop, while artists like Harry Styles or Post Malone defy genre labels altogether. Why, then, do we insist on pigeonholing rappers, particularly Black artists, into rigid categories? The label of “conscious rap” might celebrate artists like Kendrick, but it also risks limiting them, reducing their work to a single dimension.

That said, rap that strays too far from consciousness risks falling into tired, problematic tropes. When rap isn’t rooted in purpose or critique, it often leans heavily on themes of materialism or regresses into old-timey misogynistic vibes. The genre is vast and diverse, but its best work often transcends these clichés, offering something more resonant and reflective. Conscious rap matters not just because it critiques the world, but because it challenges the genre itself to be better.

Beyond the production of GNX, there’s the content. Conscious rap has always been about confronting uncomfortable truths, but GNX feels oddly preoccupied with personal slights. On “wacced out murals,” Kendrick is mad at … Snoop Dogg for finding a Drake AI Tupac song funny. He’s annoyed Lil Wayne felt snubbed over not getting the Super Bowl gig. He’s upset nobody congratulated him on booking the halftime show except Nas. There’s a palpable pettiness here, a far cry from the grand, systemic critiques that defined his earlier albums. Even his sharpest lyric—“don’t let a white comedian make a joke about a Black woman, that’s law”—feels muted compared to the searing insights of TPAB or Mr. Morale. Conscious rap, historically a mirror for societal upheaval, feels oddly self-absorbed here. Roe v. Wade? Election? War? Crickets.

Kendrick has long drawn comparisons to Tupac, and GNX leans into that legacy—sometimes to its detriment. On “reincarnated”, Kendrick writes from the perspective of his artistic influences, paying homage to Tupac’s paranoia and introspection. It’s technically impressive but emotionally distant, more about showing off his writing chops than connecting with his listeners. The track also feels oddly reactive, as if it exists to clap back at Drake’s AI Tupac experiment—a feud so obscure it barely registers. Tupac’s greatness lay in his ability to address systemic issues while remaining deeply personal. On GNX, Kendrick’s lens feels narrower, more concerned with his place in hip-hop than the world around him.

Then there’s the question of features…or the lack thereof. SZA aside, GNX lacks collaborators anywhere near Lamar’s level of critical or commercial acclaim. While one could interpret this as Kendrick using his platform to uplift emerging talents, it feels more like a statement that no one else is worthy of standing beside him. This sense of self-importance reaches its zenith on “reincarnated”, where Lamar positions himself as the reincarnation of icons like Tupac, Billie Holiday, and John Lee Hooker. Even a divine figure—voiced by Kendrick himself—steps in to confront him, injecting a fleeting moment of humility into the track. This narcissism isn’t new to hip-hop (or Kendrick), but it feels more pronounced here. Conscious rap is at its best when it’s collective, a voice for the voiceless, but GNX still feels like a solo exercise in myth-building.

For all its flaws, GNX remains an impressive piece of work. Its sound is rich and eclectic, blending influences in a way that feels fresh. Tracks like “gnx” and “squabble up” are vibrant and energetic, built for movement rather than quiet reflection. It’s not the grand statement of To Pimp a Butterfly or the sprawling introspection of Mr. Morale, but it’s substantial in its own way. The question is whether GNX fulfills the role conscious rap is meant to play. If the genre becomes too polished, too self-referential, or too palatable, it risks losing its edge. Kendrick Lamar is still one of the most important artists of his generation, but GNX reminds us that even conscious rap must evolve—or risk fading into irrelevance.∎

Words by Lina Osman. Image courtesy of Peter Hutchins.