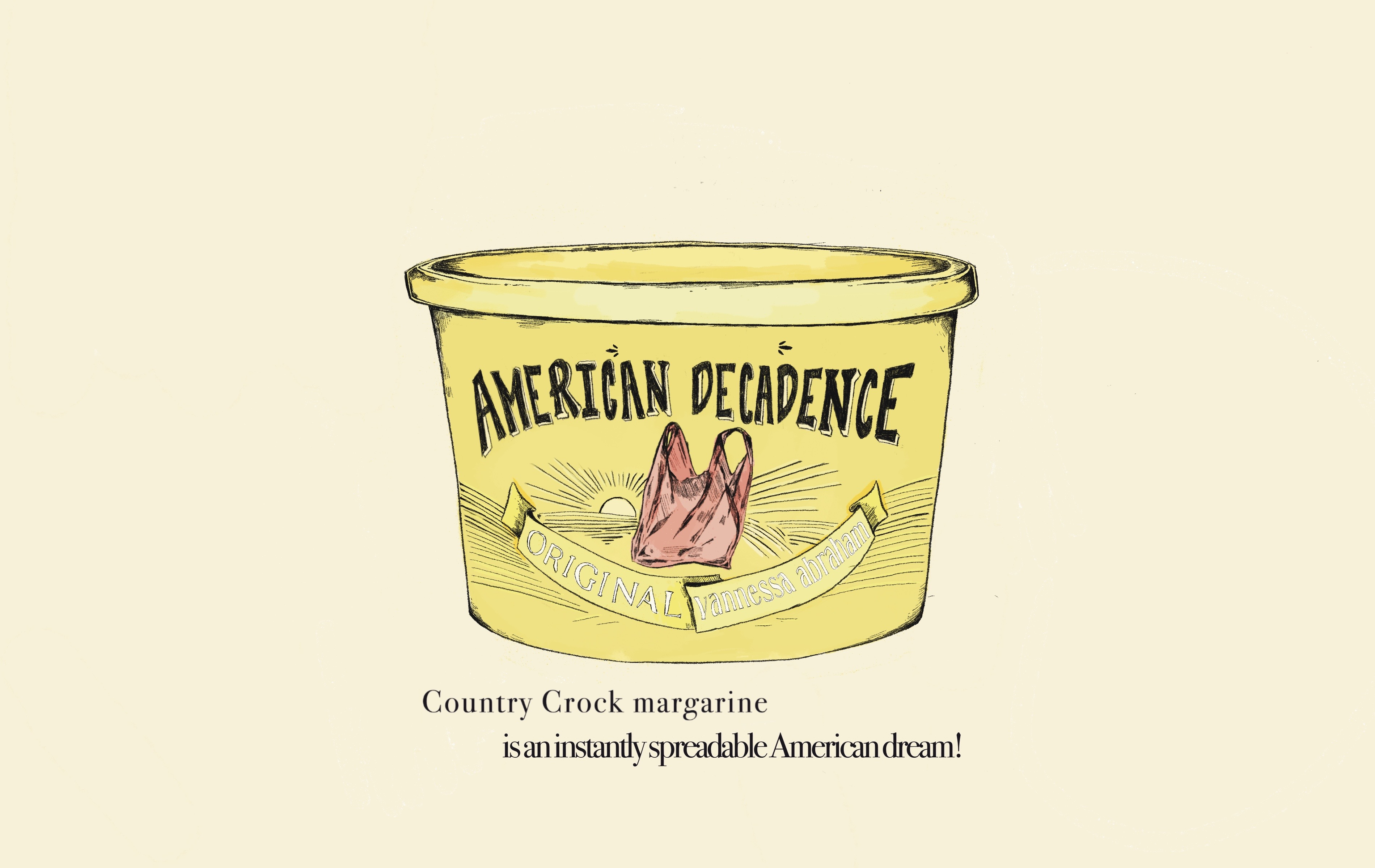

American Decadence

by Vanessa Abraham | September 19, 2024

Every time I open the fridge at my grandmother’s house, two Country Crock margarine tubs occupy the middle shelf. One of the familiar taupe containers holds margarine, while the other no longer does; instead, it is filled with chicken curry, a staple in my grandmother’s household. Within each respective tub, an American processed food and a South Indian dish masquerade as the same thing—a marker of my Ammachi’s habit of collecting and repurposing single-use plastics. Her home is a functional masterclass in the art of reuse; open her fridge to see takeout containers dispatched for daily use, peek in her bins to witness grocery bags saved as liners, or glance in her cupboards at hand-washed plastic cutlery.

But this isn’t unique to her—so many of the families I grew up around in America behaved similarly. You often refer to the disappointment of finding sewing materials in a Danish butter cookie tin, but the truth is that nobody buys an item because they think the container will be useful later. The initial reason for buying something is what’s inside, and the container then takes on a secondary function. You buy a jar of peanut butter for the brand (I swear by Jif), not the shape of the tub. Why give single-use products a double life? When I asked my family and friends about these habits, their responses were not environmentally-motivated; their replies ranged anywhere from, “it’s right there and it’s so easy”, to “why would I waste money on buying a different container?” Their main concerns were convenience and economy. We talk about convenience often—the classic, tired take of the American (read: capitalist) lifestyle as one that emphasises speed and efficiency over actual nourishment. But convenience to first generation families is a concept so deeply intertwined with scarcity mentalities and markers of assimilation. Even disposable containers become a deeply meaningful and limited resource.

It was my unawareness of precisely this that led to my betrayal of Ammachi. After she got sick, my Amma and I deep cleaned her home. To us, it seemed like a necessary intervention. After all, who needs disposable chopsticks to hand when you don’t even know how to use them? What purpose could local newspapers dating back to the early 2000s serve when you didn’t even like to read the news in English? I only understood the extent to which I hurt her a few weeks later when, in a soft voice, she asked me in Malayalam, “how would you like it if I came into your room and threw out all your things?” It was the vagueness of her use of “things” that struck me. These weren’t just throwaway pieces of cheap plastic. To her, they were objects in their own right, items worthy of preservation. It wasn’t about what was once in them, but what could be put in them in the future.

For my grandparents, who immigrated to the United States amongst the plastic boom of the 1970s, single-use goods became a sort of status symbol. These little luxuries signaled you had made it in America. There were very few American products that my grandmother both truly enjoyed and could afford, but these plastics were relatively inexpensive on her grocery shopping trips. Country Crock was one of the only processed foods she took a liking to, and the empty tubs became trophies—proof that she could adapt to a new country. I consider Country Crock to be the embodiment of American decadence. For the price of a few dollars, you could own something better and cheaper than the real thing. It’s a mirror image of butter, but far superior in taste and price point. Prized by my Ammachi for its lack of an expiration date, Country Crock is an instantly spreadable American dream suspended in a pale-yellow chemical concoction of hydrogenated fats. I don’t have any family heirlooms, but I do have a reliable Country Crock tub almost as old as I am.

***

Every time I stand in front of the refrigerated shelves at Tesco trying to pick out a meal deal, I’m overwhelmed by choice at the varying shades of cardboard. It’s easy to pick a random sandwich and shred through the carton, but I feel a little twang of guilt each time. In spite of my family’s attitudes to single-use plastics, my conceptions of convenience have shifted. I’ve picked up some of my Ammachi’s quirks that I once rejected; somehow, those plastic Sainsbury’s bags do come in handy, as do those pesto sauce jars. But, for £3.40, the packaging is a convenience I can afford to throw away. I have never once thought of repurposing the flimsy packaging of a meal deal. If anything, the idea of it actively repulses me.

Underscoring it all, as embarrassing as it is, is an urgent need for a quick meal. It requires no thought beyond picking a sandwich. Even though the nutritional value of a meal deal is likely the same as eating the packaging itself, the convenience is irresistible to me as a student. It’s a deeply unsentimental ritual. But opening the repurposed tubs in my Ammachi’s fridge, her idea of convenient packaging holds an assortment of balanced dishes. This is one of the main differences between my Ammachi and me; her relationship to single-use plastics also ties back to their ability to contain a nourishing dish. To my Ammachi, chicken curry is a muscle-memory powered recipe that’s become a weeknight dinner from almost seventy years of practice as a housewife. The convenience of her familiar Country Crock tub in holding her weekly meal prep is unbeatable as a thrifty woman. If it isn’t reductionist to say, this is her iteration of a meal deal. For her, plastics become a vessel for something that nurtures.

My own brand of convenience is strikingly empty. I’m not reusing all these plastic tubs I accumulate; I send some of them straight to the recycling bin under the guise of breaking so-called generational habits. But recently, I’ve been questioning if this is truly a pattern to break. In Ammachi’s case, saving and filling a container meant to be disposed of with traditional foods is representative of a new form of Americanness. In a country where immigrants are largely viewed as expendable, the reuse of single-use plastics is a quiet rebellion: it is an assertion of belonging. I am not meant to be discarded. I have a purpose.∎

Words by Vanessa Abraham. Graphic by Alice Robey-Cave.