Ugandan-Asian Food and Identity 50 Years On

by Evie Raja | December 11, 2022

“To remember a recipe and to produce in one’s kitchen the dish to which it refers – indeed to recall in a new time or place a taste one once savoured in another time and place – is to demonstrate a cultural memory and to ‘write’ oneself into history” (Dan Ojwang in ‘‘Eat pig and become a beast’: Food, Drink and Diaspora in East African Indian Writing’)

Crush several handfuls of unsalted peanuts using a pestle and mortar until mosaic shards slowly begin to form.

As a child, my gums would welcome the sharp edges of my fingernails as I fished out corn fibres and peanut fragments, relics of Ba’s dinner, still lodged in my museum mouth several hours after we had settled down at the dinner table. Like with every meal, she proclaimed sweetcorn curry to be my favourite. Except this time, she was correct.

The earliest memories I have of my Indian grandmother, my Ba, are closely connected with the food she religiously prepared for us. My family often reminisce about me and my sister running away from the screaming pressure cooker, our hands pressed hard against our ears. Or the smell of fresh chapattis and melting ghee that wafted from the kitchen window as we arrived home from school. It is unsurprising, then, that the strongest connection I have to my Indian – but more importantly my Ugandan-Asian heritage – is through the food we prepared, consumed, and shared. After all, Ba’s beloved sweetcorn curry is not strictly Indian, but rather a fusion of both Indian and East African flavours. Its roots most likely trace back to the initial encounters between Indians and Ugandan Africans, having been brought over to the Uganda Protectorate by the British administration in the late 19th Century. These immigrant workers functioned as intermediaries between Europeans and Africans, particularly in commerce and administration. Having worked for the British government since the days of the East India Company, Indians were entrusted with the task. Many were also labourers who helped to build the Uganda Railway connecting Mombasa in Kenya to Kampala in Uganda.

Add a pinch of mustard seeds to a pan of hot sunflower oil, letting them sizzle long enough for their sharp sour aroma to make home in every fibre of your clothing.

Far more than simply nutrition and necessity, Kasoli nu Saak (or sweetcorn curry) has its own unique biography or life history. The dish tells a complex story of just one aspect of British colonialism, that which eventually facilitated a group of ambitious Indians, many originating from Gujarat, having freely emigrated to Uganda in the early 20th Century, to set up businesses in an attempt to ‘make their fortune’ in Africa. Interestingly, Kasoli nu saak is neither wholly Gujarati nor Swahili for sweetcorn curry, but rather a fusion. Kasoli being sweetcorn in Swahili and saak curry in Gujarati. And so, with each mouthful of this dish, both the flavours and languages dissolve on the tongue. An often-relished meal which defined my childhood also serves a deeper purpose. It illuminates a complex relationship between three countries spread across three continents. My father would often attempt to explain this to me whilst I sat disappointed that ‘my dish’ had failed to appear on the restaurant menu.

History, like a restaurant menu, is selective. We have a curated perception of the past through a snapshot of details or dishes – The East India Company, Partition, Idi Amin or chicken tikka masala, samosas and dhal. The mundane is often forgotten beneath the sensationalised; recipes rich with history replaced by rumours of a dictator’s cannibalism. (It was rumoured Idi Amin kept human heads in his refrigerator and apparently revealed in 1976 that he had ‘eaten human meat’, admitting ‘it is very salty, even more salty than leopard meat’.) Indeed, even on a personal level, the nuances of my own family history are lost when I refer to my grandmother as merely Indian. The core of her identity, and mine, is distinctly both Gujarati and Ugandan-Asian.

Shake powders of chilli, turmeric, cumin, coriander and garam masala into the pan as if you are in the middle of a busy street on Holi.

The memorised recipes my pregnant grandmother carried to the UK alongside her seven children never made the archives. Favoured instead were incomprehensible statistics, like the 27,000 Indians who sought refuge in the UK, or the descriptions of resettlement camps – such as Doniford or Tonfanau. These facts and figures cannot authentically capture the lives of those uprooted and given a mere 90 days to leave. A three-times-a-day ritual has the power to reveal far more about the lives of the 76,000 individuals expelled from Uganda 50 years ago. Their recipes can be re-created, re-consumed and relived. History can be experienced as rich tomato sauce packed with garam masala invades the back of your throat, a full sensory understanding of what was forced to immigrate across a continent.

Yet sadly, this history and these dishes remain in obscurity. When, however, you know for what to search, recipes and tales from individuals working to preserve these peripheral cultures emerge. A prime example is the food writer Meera Sodha, whose parents were also political refugees from Uganda. As a regular columnist for The Guardian, I am grateful she has a platform from which to share recipes that are often rooted in Ugandan Indian cuisine to individuals across the country. As if in protest of being largely ignored by historical records, the biography of sweetcorn curry continues. Now prepared and enjoyed in a suburban town in Manchester, it reveals a uniquely complicated diasporic community. These recipes form a mostly underground archive, potently capturing the ‘everyday’ dismissed by the media and written records.

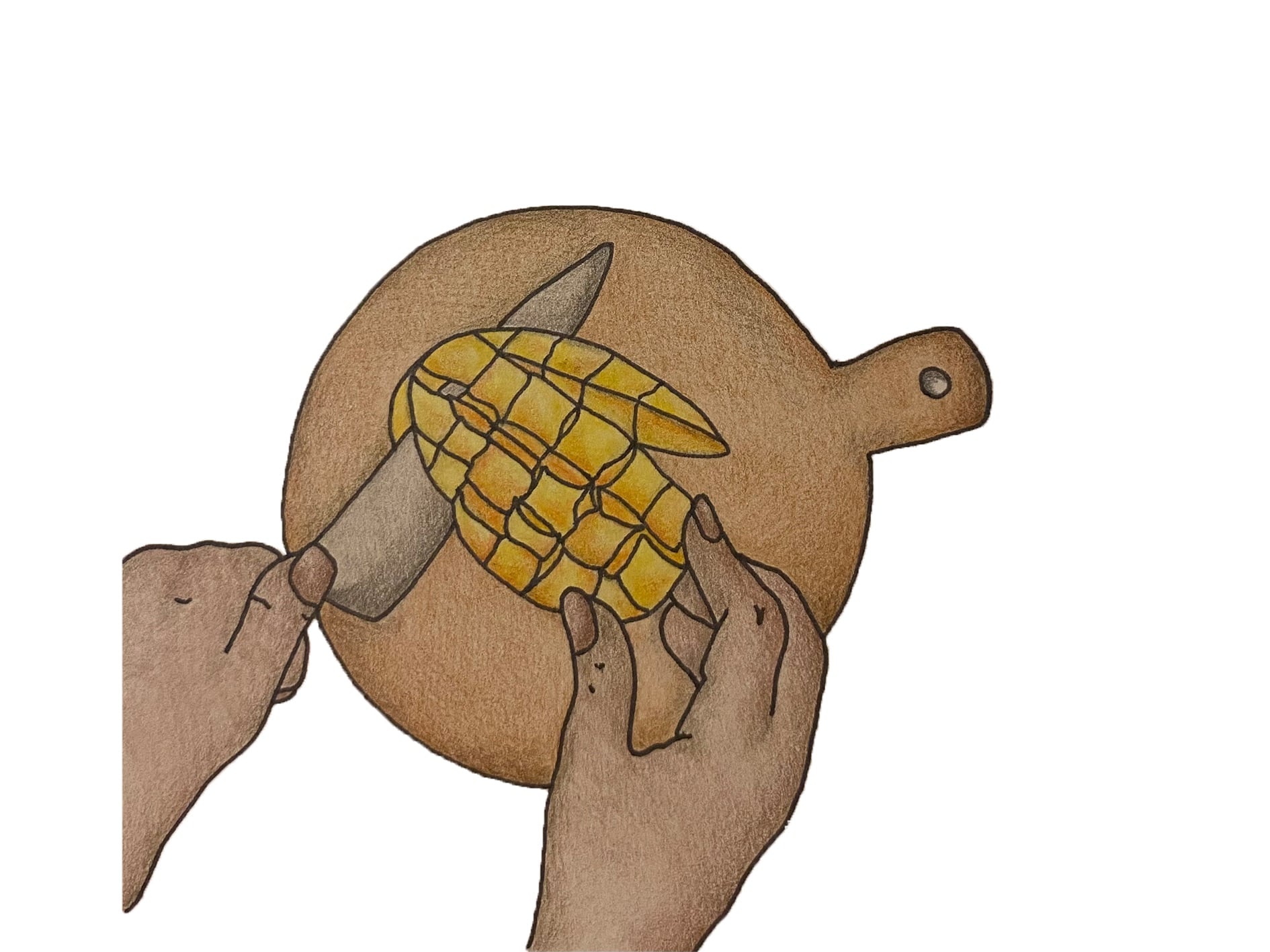

Gently unwrap the fresh corn cobs and slice into cylinders that can be easily enjoyed by children and grandparents alike.

Aside from sweetcorn curry, I have only recently begun to recognise many of my childhood recipes as characteristically Ugandan-Asian, thanks to Alibhai-Brown’s The Settler’s Cookbook. I was surprised to see her write of the “slices of sour, unripe mangoes dipped into a concoction of chilli powder, salt [and] sugar” that I would often greedily try, but rarely enjoy. It conjured a memory of my grandmother placing this delicacy on the kitchen table in a little glass bowl, mostly ignored in favour of her steaming rice and pea and potato saak. I am grateful to Alibhai-Brown for preserving even what feels like the most insignificant of snacks. Such flavours can transport me fifty years back, to a Uganda now lost to time. These dishes invite me into my father and grandmother’s experience of Uganda, which is at the core of my family history.

Tip in a can of tomatoes to introduce some sour sweet competition to the army of spices.

“Fruit from two trees nourish me” is how Avan Jogia expresses the biracial experience in Mixed Feelings. At least in my case, that meant it was difficult to commit to learning my father’s tongue for threat of excluding my mother from our jokes and conversations. Religion was treated in a similar way. Unable to side with either Christianity or Hinduism, my parents chose a combination of good morals and a celebration of both Diwali and Christmas. Yet, when we sit down and share a meal, I feel whole, consuming a culture I am often disconnected to. Nina Minya Powles expresses this in ‘Hungry Girls’. Even after nourishing her identity through Mandarin lessons for three years, there are days when the language fails her, days when “food feels like the only thing I have to tie me to this home my family brought to me from far away.” Food is an accessible inlet to a culture, but also a sense of security and familiarity.

“I take a bite and my worries melt away. I’m home and also far away from home, in one bite.” (Nina Minya Powles in ‘Pan Fried Dumplings’)

It seems ridiculous, therefore, that I failed to consider the role that food played during my father and his family’s time living at a refugee camp in Doniford, not nutritionally but as a “powerful index of a sense of security and belonging” as described by Ojwang in ‘Eat pig and become a beast’. A period of immense adjustment made more challenging by the unforgiving climatic and dietary differences. Of course, there is the obvious point that both British cuisine and the produce available in 1970s Somerset was far from that which they enjoyed in Uganda. However, when thinking more laterally about the integral role food plays within these spaces, shared meals and the act of cooking can, as Jordanna Bailkin argues in Unsettled, Refugee Camps and the Making of Multicultural Britain, serve as a “crucial reminder of what they had lost in expulsion.” More than this, food, and the accompanied cooking practices, have the potential to uphold the social life and kinship networks uprooted through migration. This was particularly challenging as many of the Ugandan-Asian resettlement camps insisted on refugees eating the food that was prepared for them by volunteers in large dining halls, imposing a cooking ban throughout the site. The stories Bailkin shares of illicit cooking and the example of two enterprising brothers who opened a shop to sell “authentic” Indian spices reveals a community reaching for small moments of independence and normalcy. In fact, at the Tonfanau camp, such happenings prompted each family to be given £5 to buy an electric plate. Whilst an amusing tale, these electric plates were particularly important in allowing women to “express cultural preferences and keep up household rules” through the act of preparing food. Bailkin quotes one woman who expressed that “as long as I could cook one meal, I was still a mother looking after my family.”

Tear up a small handful of coriander leaves and scatter on top of the steaming golden saak, moments before it is ready for presentation.

Today, Doniford refugee camp is just a memory for my Ba. Preparing these dishes now is a form of archiving and storytelling for her, or what Ojwang describes as a way to “animate the past in the present” through the “material agency of food and the acts that go into its preparation and enjoyment.” Recipes and meals enjoyed are often imprinted on our minds, having stimulated all of the senses as they are prepared and eaten. According to psychologist Susan Krauss Whitbourne, this is because “food memories involve very basic, nonverbal areas of the brain that can bypass your conscious awareness.” She uses this to explain why “you can have strong emotional reactions when you eat a food that arouses those deep unconscious memories.” Even those memories stored within our consciousness are strengthened as we recall not just an image of the meal but its flavour, the sound of its preparation and the conversation we had whilst eating it. This connection between food and memory struck Powels’ when her grandmother, her Popo, who suffered from dementia and “could never remember whether she’d turned the light off in the upstairs room,” immediately recalled the recipe of her chicken and aubergine curry. “It was years since she last cooked but still knew it by heart.”

I will never fully understand what it was like to live in Uganda, or to store the painful memories of leaving to begin a new life in England. But Ba’s rich peanut sauce, unripe mangos and mogo chips doused in chilli powder and fresh lime allow me to taste their home in Jinja and share in my father’s childhood and those tender moments of joy. ∎

Words by Evie Raja. Art by Lottie Hassan.