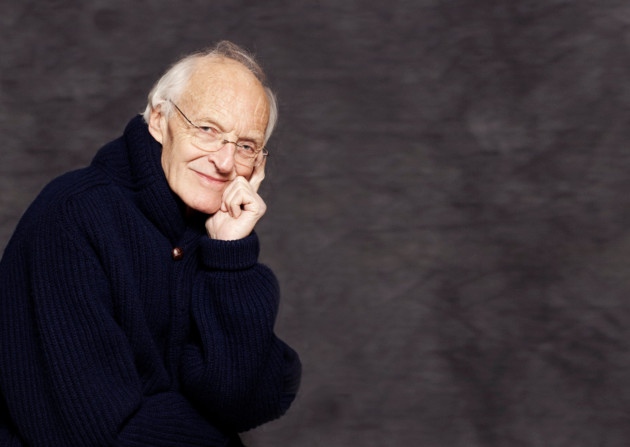

Coffee With Michael Frayn

by Tom Ball | March 8, 2016

Search long enough and you’ll discover that there exist some neat patches of parkland on YouTube that haven’t been marred by the graffiti of endless Vevo commercials or the dog-shit vitriol of the comments box. One such sequestered glade is the modest archive of seventies BBC documentaries, a trove of early social reportage, from a time when television cameras and a remarkably dark-haired David Dimbleby first inveigled their way into communities (Born Black, Born British, 1972), schools (The Best Days, 1977) and homes (The Family, 1974). But surprisingly, alongside these prototypes of the production line that would eventually churn out the Kardashians and Davina McCall, can be found Three Streets in the Country, a paean to suburbia, written and presented by the novelist and playwright Michael Frayn.

Frayn occupies a unique position in the modern British canon. “Bernard Shaw couldn’t do it, Henry James couldn’t do it, but the ingenious English author Michael Frayn does do it,” quoth John Updike. That is: to write for the stage and the shelf with equal success. For his plays he has won the Tony Award and the Laurence Olivier Award; for his fiction he has won the Somerset Maugham Award, the Whitbread Award and been nominated for the Booker. And, for what it’s worth, he is, to my mind, one of the greatest comic authors of the past century.

It was, therefore, with bemused pleasure that I stumbled across Three Streets in the Country several years ago. Featuring a young—and frequently stern—Frayn, it’s a meditative programme, pitched around the semi-academic tone in which the BBC would come to specialise, discussing London’s rampant suburbanisation in the twentieth century. More accurately, however, Three Streets in the Country is a televisual reminiscence, as Frayn returns to his hometown of Ewell, in Surrey, to wander and remark upon those three well-kempt streets of his childhood, rustling through old thicketed haunts and peeping over creosoted fences to the soundtrack of old English folk ballads. It was, he says, the perfect place to grow up, and the perfect time too, for the war meant that there was little traffic and many bombsites and abandoned buildings for children to play in.

Three Streets in the Country was broadcast over thirty-five years ago; Frayn’s own residency in Ewell began over eighty years ago. Now, following a lifetime spent living in the inner city, first in Manchester, where he worked for the Guardian, and later in Camden Town, where neighbours included Alan Bennett and Mary-Kay Wilmers, he has moved back to London’s fringes.

The house where he lives with his wife, the biographer Claire Tomalin, is shielded from the road by a thick white-washed wall, high enough only for gawpers on passing double-deckers to see over. The tall wall’s density becomes clear to me as I press the intercom and fight to make myself heard over the yowl of the traffic. Beyond the wall it is markedly quieter: a square and carless enclosure of gravel introducing the symmetrical and steep-roofed house.

I ring the doorbell and wait, squirming somewhat with forced nonchalance in the suspicion that I am being watched through the spy-hole (a natural sequitur, perhaps, from my muffled declaration over the intercom). The door then opens and Frayn stands before it. I am welcomed in to a hallway lined with books, where I take off my shoes (the day is wet) and follow him into the kitchen for coffee.

Born in 1933, Frayn may have missed the second world war, but he was an early conscript into the west’s war on communism, selected for a Russian interpretation course as part of his national service. However, as a self-labelled communist, he took to the course with conspiratorial enthusiasm, so much so that after two years of service he continued his study of the language at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Though the initial political impetus soon wore off, Frayn has since used his Russian to become Britain’s most eminent translator of Chekhov.

An aside—I am both a Russianist and a fan of Chekhov, so I suspected that we might have something to talk about. What I hadn’t foreseen though was the fertility of the common ground yielded by our respective tertiary educations: in spite of the sixty-year and seventy-mile expanse that divides us, collegiate conversation is curiously indefatigable, allowing us to trade a succession of minor anecdotes and probe at potential mutual acquaintances. One English novelist described the interview as an “anxious and exhausting” affair “with the interviewer fielding about eighty per cent of the nerves”; but as we stood waiting for the coffee those wheedling anxieties began to dissipate with the shrill hum of the Nespresso machine.

We move next door to a sitting room darkened by the wall’s obscuration of the low winter sun, and he recounts to me the story of how he came to realise that acting wasn’t for him, when he nearly pulled down half the stage set in a student production of Gogol’s The Government Inspector while attempting to exit a scene through a jammed door. Neither, though, did his fledgling theatrical endeavours offstage meet with much success. As he explains, each year a West End theatre would produce a Cambridge Footlights Spring Revue; but in the year that Frayn wrote the skits, the show was unanimously rejected by London’s producers, who deemed it too abstract. In what he terms a “sour-grapes” reaction to the flop, he wouldn’t write for the stage again for fifteen years.

I listen to these stories with wide-eyed, parted-lipped attentiveness, feeling a little boyish in my shoeless state, as though I were listening to the battle stories of an avuncular relative. My captivation is therefore largely responsible for the lack of direct speech thus far; for I had first forgotten, and then been reluctant to acknowledge, my dictaphone, which, to extract from my pocket, seemed like a gesture of hostile intent. So then we talked about Chekhov and the red light listened on the table between us. It tells me now that:

“The translating business began in the nineteen-seventies or eighties when the National Theatre asked me to translate some Goldoni, to which I said that I didn’t think I could do it because I didn’t have any Italian. But the dramaturg said, ‘Good God, you don’t need to read Italian to translate Goldoni! Just go out and buy some standard translations and hash them together to make your own version.’ So I duly went out and bought some Goldoni translations—but I couldn’t make out at all the sense of the original.”

In the end, Frayn responded by asking if he might translate instead from a language that he did know, and after a brief skirmish with Tolstoy’s unmemorable Fruits of the Enlightenment, he took on the task of working his way through Chekhov’s theatrical oeuvre. He is now not only Chekhov’s finest English translator, but also his most complete, having translated all of his plays with the exception of The Wood Demon and Ivanov.

But translation is a difficult and often thankless task. As Cervantes complained, reading a translation can be like “like looking at the Flanders tapestries from behind: you can see the basic shapes but they are so filled with threads that you cannot fathom their original lustre.” Frayn, however, is confident in his powers to convey the original: “translating is wonderful. To translate a play well, one must become utterly marinated in it. The more deeply I became involved in Chekhov’s plays the more taken I was by them, and struck by surprising discoveries—that it’s all plot! Why those last four plays work so well with audiences everywhere is that they are incredibly tightly plotted and every line is driving forward the business of the play. But it’s so well done that it doesn’t seem like that.” I don’t need the dictaphone to remember how animated he became here, the intonation of his speech rising and falling with ever greater cadences. His respect for Chekhov is clearly enormous. The vocal undulations reach their zenith with the mention of Donald Rayfield’s biography of the Russian, which was written following the opening of supressed archival documents pertaining to Chekhov’s private life: “he had always been considered this rather saintly doctor. But in fact he was an extraordinarily sociable man, who enjoyed drinking and eating just as much as he did writing. And his sex life, well … It was very powerful indeed.”

He is quick to stress the humour in Chekhov (“It took a long time for people to realise that much of the comedy lies in mocking and self-deprecation”)—unsurprising, perhaps, given that Frayn also first found success on the stage through farce and comedy. And, though I am wary of making this all tie together too nicely, the comparison between the two writers may be further stretched. Chekhov too was, after all, accomplished as both a playwright and a prosaist. But he bats away the suggestion modestly, instead acknowledging his debt to Chekhov. The discovery of plot in Chekhov is particularly important for him, a personal revelation which he invokes as a rebuff to the plotlessness advocated by modernist theory. Plot is, for Frayn, “the net which fiction can impose upon life … to give it understanding … to bring out something in the world that is difficult to grasp without it.”

The discussion of plot ends with a disagreement over whether Martin Amis’s Money is a plotless novel, leaving a minor silence. The dregs of my coffee are long cold and I start to think about taking my leave. I extinguish the red light and we walk to the front door where I lace up my shoes as he courteously holds the arms of my jacket out for me. And only then do I recall Three Streets in the Country, the documentary I had come across years earlier. Standing by the opened door I remind him of it and once more his features enliven. “Where did you find that?” he smiles. I ask whether his current home is much like Ewell and he says not, but notes the familiar echoes and the congeniality of suburban living. “As I think I said in the film, people traditionally look down on the suburbs, but most of the population of London lives in them. It is ridiculous that they should be so patronised. We all live our lives with the same degree of seriousness, painfulness and pleasures as each other.”

Photo: Jillian Edelstein