Mostar: A View From The Bridge

by Sara Semic | November 27, 2014

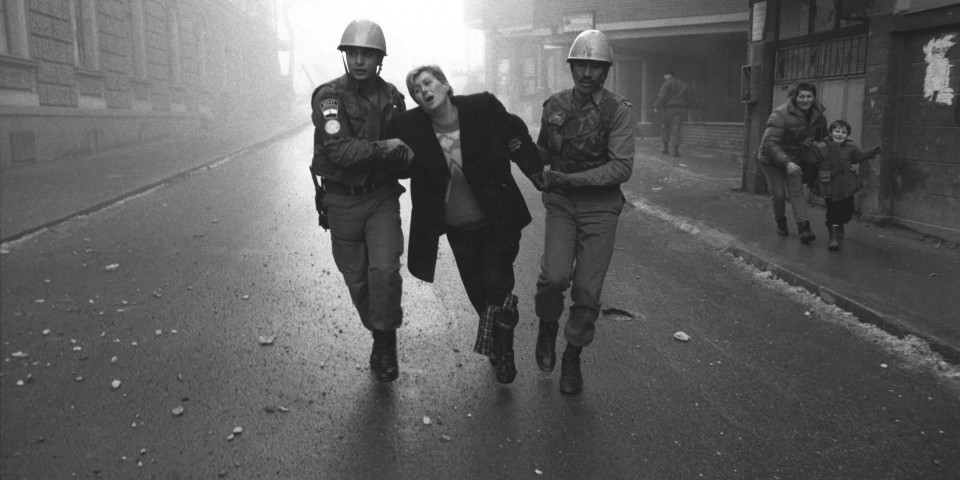

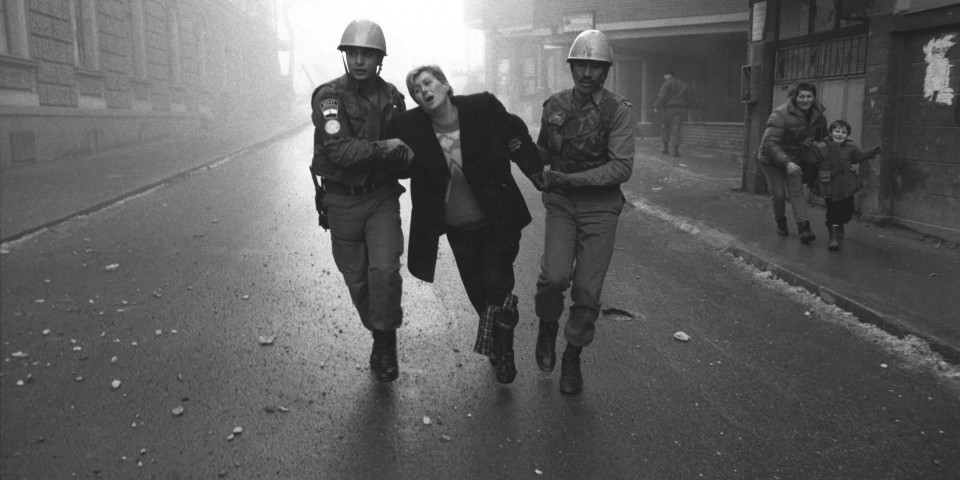

Bosnia & Herzegovina has been brought back into the international spotlight after a decade of political and socio-economic inertia. The powder keg of frustration over the unemployment rates of around 43% (63% for youth unemployment, with two in three young people without a job) and political stalemate, which has stalled the country’s progress towards European Union accession, finally erupted in February this year. Disgruntled workers are rising against state-sponsored plunder – where public money is handed over to cronies who infiltrate the shells of the Yugoslav-era socialist industries, before selling off the assets and declaring bankruptcy, leaving workers unpaid. The outbreak of anti-government demonstrations, beginning in the northern town of Tuzla but quickly spreading to other cities including the capital, Sarajevo, has even been dubbed the ‘Bosnian Spring’ by some analysts.

But a permanent stumbling block in the way of political consensus and economic progress is the ethnic tension between the Bosniak, Serb and Croat communities. Intervention after the Bosnian war of 1992 to 1995, during which some 100,000 people died and two million were displaced from their homes, brought peace at the cost of ethnic segregation.

This ethno-political impasse is placed under a microscope in the small and concentrated city of Mostar which, nestled amongst high mountains and physically hidden from the rest of the world, has been ignored by the media. Reports from tourists give the impression of a beautiful place with a united identity anchored in a culturally rich history; the continuing effects of war are often misunderstood by the passing visitor.

On a hot summer’s day in Mostar, I worm my way through the horde of tourists all scaling the slippery limestone steps of the Stari Most (Old Bridge), fanning themselves with bus tickets and striking poses against the backdrop of the emerald green river Neretva. The crumbling old town and cobblestoned streets which surround the bridge heaves with locals who, like their goldsmith predecessors, sell authentic paintings and copper or bronze carvings of the Stari Most. Along with collectable vintage lapel pins and the odd ‘Dolce and Gabbono’ purse, the area is reminiscent of treasure trove Middle Eastern bazaars. There is a sudden eruption of excitement as two of the Mostari divers prepare to jump from the apex of the 22m high bridge; a tradition stretching back over centuries.

The original bridge which was built under the orders of the Turkish sultan in 1566- and the city of Mostar itself- was once synonymous with the idea of a multi-ethnic Bosnia & Herzegovina, a place defined by bridge-building between communities, nationalities and different religions. The destruction of the bridge in turn symbolised the destruction of this idea, and an end to centuries of peaceful coexistence. As soon as the conflict of the war was over, meticulous plans began to restore the centerpiece of the city, a project that cost £5 million. Ever since the bridge was reopened in 2004, it has been attracting tourists for its architectural beauty and diving tradition: for $25 and at your own risk, you too can plunge into river.

For the people of Mostar, the ‘new’ Old Bridge is a complex symbol. It is a gleaming white beacon of hope and progression, symbolizing a coming together of the old and new – a feature that defines the city and its people. Yet it also acts as an unwelcome reminder of the war, which generated the political divisions along sectarian Christian-Muslim lines that characterize Mostar’s society and which have shaped its topography. The west bank is held by the Catholic Croat population, who make up roughly 34% of the city’s demographic (although only unofficial estimates on the ethnic breakdown exist since the war), whilst the Muslim Bosniaks, comprising of 35% of the population, make up the majority of those living on the east side. This division is near invisible to the eye of the ordinary tourist. There are no outward signs to differentiate the two groups, in physiognomy or dress, and although religion appears to be an important token of self-identity for Mostar’s inhabitants, for many secular Bosniaks an awareness of their Muslim identity has more to do with ancestral and cultural roots than with faith. The relaxed and idiosyncratic traditions of observance amongst Bosnian Muslims are part of the legacy of Tito’s atheist regime and socialist Yugoslavia; you won’t spot many headscarves or Burkas amongst the Muslim women in Mostar, who identify less with the Arab world and more with the West

Mostar feels sadder than its more prosperous and cosmopolitan neighbour Sarajevo, where business is booming and foreign investment is visible. Prising apart the layers to the city, beyond the medieval old town, it becomes apparent that the sectarian divisions have woven into the social and cultural fabric of daily life. Schools and higher education institutions on the east and west banks of the river run different syllabuses, primarily rooted in their use of different languages, with Croats speaking the Croatian language, and Bosniaks using the Bosnian language. In reality however, the differences in the two are only noticeable in the case of certain words such as bread, which translates as ‘kruh’ for Croats, and ‘hlijeb’ for Bosniaks. This divide in education is carried through into university level, and seen within the only two state universities in the city. One, the University of Mostar, uses the Croatian language, whilst the University ‘Dzemal Bijedic’ of Mostar, on the east side, has stated Bosnian as its official language since 1994. Despite the higher education reform and the signing of the Bologna declaration, which forced both universities to put aside their differences in order to make themselves competitive on a regional level, they continue to operate in isolation.

Each side has its own electricity provider, policemen, telephone network and postal service. There are even different TV channels; the Croatian HRT 1 and HRT 2 channels, which broadcast the main news and entertainment programs on the west side, are replaced by BHT on the east side. Zeljka, who lived on the west side before the war forced her to flee the city in her twenties, recalls how before war broke out, Croats and Muslims interacted normally. “Some of my closest friends are Muslims” she tells me. “It wasn’t divided like it is today. I barely recognize my hometown.”

For the younger generations, however, this split is just a social fact in daily life. Teens living on the east side generally won’t venture further than the Mepas shopping center or Gradski bazen (the city’s outdoor pool) on the west side, and only a handful from the west will enter the east side. Marija, who has lived on the west side her entire life, tells me how this is usually only when they need to buy discounted clothing from ‘Haris’, an outlet boutique. Marija, who is twenty, tells me how growing up, all of her friends were from within her neighbourhood and raised similarly to herself. However, after leaving high school and starting university her friendship group expanded in parentage as well as size. “There are some narrow-minded people though, who will gossip if someone is dating somebody from the other side” she says. “I just feel so ready to move out of this city”. According to surveys, she is not the only one, with 70% of young people saying they would also leave if they had the chance.

In Mostar, the high level of political corruption has succeeded in creating a small circle of people with disproportionate wealth, who invest in multiple private properties and huge shopping centers, whilst the majority struggle to make ends meet. Looking around, the disproportionate amount of investment into the creation of large, glassy shopping centers and department stores, which sit uneasily alongside bullet-riddled former hospitals and empty homes, is marked. “People don’t need more shopping centers. We need better infrastructure” Zeljka tells me. “More factories and libraries – that would be a start.”

The spirit of the February protests appeared to burn out by April, and it is hard to foresee what the situation will be like in Mostar in the near future. For a tourist, the terraces outside the old Turkish houses offer an idyllic setting for a drink, and prime position from which to watch the divers make a plunge.

The two young men finally stretch their arms and take the leap, to the applause of tourists around me, who perhaps take a mental picture of the moment to add to their new bronze carvings and miniature stone keepsakes of the bridge.

For now, Mostar can only offer with open arms its rich landscape and richer history to curious tourists. In this beautiful but still war-wounded city, the metaphorical bridges are yet to be constructed.