A Homage to the Women who Inspired Picasso’s Work

by Rachel Turner | March 16, 2023

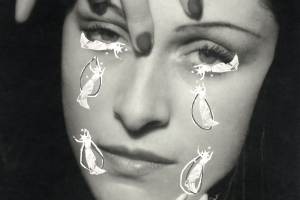

Think of Picasso and it’s impossible not to envision the women he painted, loved, and tormented. But the uncomfortable reality is that the tender intimacy between artist and subject did not translate beyond the canvas. The lives of the women who inspired him tell a more complicated story, marked by moments of intense pain inflicted by an artist who used women to bolster his creative identity. It is almost a truism that great art is often created by morally problematic people. A rather crude but crucial indication of this is the simple fact that out of the seven women romantically involved in Picasso’s life, two committed suicide and two went insane. As creative people in their own right – innovative, imaginative, and inspired women – they deserve to be reframed in a way that shines a spotlight on their resilience and creativity, independent of the man who painted them. A new series of portraits emerge of real women who suffered at the hands of power. In switching the focus from the maker to his ‘muses’, highly romanticised notions can be replaced with authentic narratives of women whose agency, for so long, has been ignored. Marie-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, and Francoise Gilot all lived extraordinary lives that transcended Picasso’s imagination.

I.

The date is 1927. At a street corner outside Galeries Lafayette, a beautiful young woman has come to buy un col Claudine and matching cuffs. Picasso, spotting her there, marches straight over: “I’d like to do a portrait of you… I feel we’re going to do great things together.” And so, on a cold January morning, one of the art world’s most famous love affairs begins. Yet perhaps unsurprisingly, this promise of an artistic collaboration never came to fruition: Marie-Thérèse Walter was painted and perceived but never actively participated. Coercive and misleading, Picasso constructed a power dynamic where Walter inadvertently found herself at once inspiration and at the mercy of power.

With blue eyes and golden curls, Walter’s influence on Picasso’s style is clear from the beginning. The geometric forms of his Cubist work faded whilst sinuous curves and enveloping arms took their place. The Dream (1932) is awash with lavender, lemon yellow and pale green, from which a soft and sensual personality emerges; her lilac skin and blonde hair show an emotional sensitivity, unlike Picasso’s previous work.

At just 17, Picasso was 28 years Walter’s senior. She was a fashionable girl living with her mother and sister on the outskirts of Paris. Picasso was already married to Olga Khokhlova, a member of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, who suffered from an intense nervous disorder. Soon, Walter was travelling into the city to visit him and hiding out in his studio, which Olga was rarely allowed to visit. This is perhaps the first instance of Picasso’s conflation of lover and ‘muse’, the unavoidably complicated overlap between the personal and the public.

Picasso’s work from this period only refers to Walter in code: first as a cryptogram, with the MT of Marie Thérèse intertwined with P for Picasso. This became more explicit as his marriage to Olga disintegrated further. The glaring age gap between ‘muse’ and artist is a disturbing but recurrent aspect of Picasso’s relationships. Vulnerable to exploitation, both on and beyond the canvas, the disparity between a young woman’s self-perception and the representation by her painter is problematic. As Walter transitioned from girlhood to womanhood, her identity was being shaped by a much older man. Completely unrestrained, the artist’s conscious construction of female identity reveals a pattern of predatory, patriarchal attitudes. Forever defined by the male gaze, and restrictively framed by his art, the self-perception of Walter as his muse is subsumed by the more dominant force.

II.

To many, Dora Maar is the Weeping Woman; her sadness is forever immortalised in Picasso’s 1937 painting. “All portraits of me are lies,” Maar later said – “not one is Dora Maar.” By distilling her identity and capturing her essence in a two-dimensional format, Picasso had complete control over how she was presented. It is no surprise, therefore, that the rest of Maar’s life reads like a reclamation of self, an effort to lift herself from the canvas.

For here is a brilliant woman: one of the most original and commercially successful photographers of her generation, and exceptionally talented in her own right. She travelled to London and Barcelona during the Great Depression to capture socially conscious street photography. Maar soon became a rising star in Surrealist circles: her photograph, Père Ubu, became an emblem for the movement after it was exhibited in London at the International Surrealist Exhibition. Not only were very few photographers admitted, but she was also the only artist whose work was exhibited in all six international exhibitions. Her sizeable contribution to contemporary culture represents an impressive career – forged through her own determination and talent – and crucially all before she met Picasso.

The eventual meeting of two of Modernism’s great titans was bound to be dramatic. Legend has it that they met in the famous Café Les Deux Magots, with Maar playing a game where she stabbed a knife between her fingers to Picasso’s excitement. Their relationship lasted nearly nine years, inspiring many of his most significant pieces, including Guernica. It was Maar who taught Picasso the darkroom techniques used in the large 1937 oil painting, and it was Maar who encouraged him to get into left-wing politics in response to the bombing. Her distinctive black, white, and grey photography was a blueprint for Picasso during this period of political upheaval: the monochrome palette of Guernica is reminiscent of Maar’s unique photography. One medium seems to bleed into another: the artist-muse dynamic slides into a creative mutuality. It is therefore quite difficult to fit Maar into the mould of the ‘muse’. A commitment to her own development as an artist was clearly intrinsic to how she perceived herself, which tempered the power imbalance between subject and artist.

Her biographer, Victoria Combalia, concluded that she was “too intelligent, too stubborn, and too unstable” for Picasso. And so, in 1946, as the dust of war settled across Europe, they broke apart. Retreating to a beautiful 18th-century townhouse in the South of France, Maar sought refuge in painting and photography once more. Taking the barren landscapes of the Luberon region of Provence as her subject, she focussed on the spaces of land and sky. The vastness and loneliness of her work reflected a longing for expansion after years of confinement.

III.

When Françoise Gilot decided to take her two young children and leave Pablo Picasso after 10 years together, he told her, infuriated, that she was “headed straight for the desert.” How wrong he was.

Life after 1953 took her to America, where she retreated to her studio. She went on to master printmaking techniques such as lithography and aquatint. In 1980, she began her celebrated Floating Paintings, so-called because these vast canvases – painted on both sides and supported only by a wooden bar at the top – hang away from the wall and seem almost to levitate.

In an interview with Vogue, Gilot – living in New York and still painting every day at the age of 90 – candidly looked back on her extraordinary story which began in Paris in the aftermath of the First World War: “you always survive if you think you should. I didn’t ask permission to be who I am.” Perhaps there is more to the Floating Paintings than first meets the eye. Like the canvases themselves, Gilot appeared to be miraculously self-contained and self-supporting. It is easy to imagine the artistic processes and the artist’s psyche as deeply interwoven, as her immense talent and fiery independence seem inseparable.

Picasso loved these women because they reflected his own talent. In blurring the boundary between public and private, his oeuvre sought to reduce the essence of a ‘muse’, by objectifying and distilling her on the canvas. Some women survived this treatment, while others did not. Gilot emerged from Picasso’s shadow refusing to be categorised or defined by the man who painted her: her time as a ‘muse’ was only a short chapter in a long and creatively fulfilling life. However, for Walter, the cost of his artistic exploitation had tragic consequences and her life after Picasso was cut short. Even if we conclude that the painter-muse dynamic is a bountiful source of artistic inspiration, we can still find that it reveals a pattern of misogyny which subsumes the woman’s identity as a creative force in her own right. And so, in reappraising some of the women depicted in Picasso’s greatest works, a new series of portraits emerge that counteract the image of the ‘muse’ as a loved, but silent, object who inspired the male artist. In recovering their silenced creativity and painfully inflicted wounds, an agency is restored, and three extraordinary stories are brought to life.

Words by Rachel Turner.

Art by Dowon Jung.