Revenge of the Muse

by Grace Campbell | March 21, 2020

Near the end of the Tate Modern’s Dora Maar retrospective, the largest so far in the UK, there is a recording of a conversation between the eighty-seven-year-old Dora Maar and Francis Morris, now head of the Tate Modern. In the conversation, originally recorded for the Tate’s 1995 Picasso retrospective, Maar and Morris are discussing ‘Guernica’, which is projected on the gallery wall.

Francis Morris: Would you like to say anything about the painting? It’s a marvellous opportunity for you to leave a memory.

Dora Maar: Well, I have yet another contribution. It’s the lamp. The lamp. I was the one who had put it in a painting, and then he took the electric lamp. The light, the electric light, is inspired by a painting of… my painting.

Francis Morris: Oh, the light in ‘Guernica’ was in a painting by you?

Dora Maar: Yes, but it’s not very important.

Francis Morris: But that’s very interesting, because people have written books about the light.

Dora Maar: Yes.

The painting to which Maar is referring is believed to be ‘The Conversation’ of 1937. It depicts two women, one dark-haired and one blonde, in plain grey dresses. Both are seated, the blonde woman at a small desk like a school-desk, in an austere, red-painted room. There is an electric lamp overhead that is indeed similar to the one in Picasso’s ‘Guernica’. The two women – widely considered to be Maar herself and the nineteen-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter, with whom Picasso was living during the beginning of his relationship with Maar – are stiff and straight-backed, like dolls. The dark-haired figure faces away from us, towards a door which is open into darkness. The blonde woman faces outwards towards the viewer, her features strongly reminiscent of Picasso’s many portraits of Marie-Thérèse: heavy-lidded eyes and a mild, enigmatic smile like that of a Grecian statue. Despite the title, little conversation seems to be taking place between the two women. Nevertheless, it appears less a painting of antagonism than of uneasiness – a painting that depicts an impasse, rather than a feud.

‘The Conversation’ is thought to be the only direct reference Maar made in her work to the situation with Marie-Thérèse. There is a reluctance, an unyielding quality to the representation, as though Maar is plainly rejecting either the painful and acrimonious love-triangle in which she found herself, or else the temptation to make a definitive statement on it. Picasso painted Maar’s face over and over again. Yet when she comes to paint herself, she paints the back of her own head.

The painting is one of few in the exhibition, which is mostly devoted to photography, Maar’s preferred medium and the one in which she was most accomplished. Maar took up painting at the encouragement of Picasso, with whom she began a relationship with in the turbulent year of 1935, and her style in the early years is clearly influenced by his. What is striking about the exchange with Francis Morris, however, is the matter-of-fact way in which Maar states that Picasso might also have been influenced by her. As the exhibition plaque notes, Maar taught Picasso various photographic techniques, and it does not seem impossible that the monochromatic palette of ‘Guernica’, which many have likened to a photograph, may have been in some way influenced by Maar’s darkroom. Maar herself, who documented the creation of ‘Guernica’, described it as an “immense photograph”.

Maar is the latest of several twentieth-century female artists to receive a major retrospective at the Tate, following on the heels of Lee Krasner and Natalia Goncharova in 2019. Both Krasner and Goncharova have suffered at times from critical neglect – Krasner was long invoked only as the wife of Jackson Pollock, another of the most famous artists of the twentieth-century, and another member of the boozing, philandering school. Also in 2019 was the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood exhibition, which focused on the artistic output of the women who were the lovers and muses of the Pre-Raphaelites. Finally, 2019 saw the publication of Self-Portrait, the memoir of painter Celia Paul, who as an eighteen year-old student at the Slade School of Art entered into a ten-year affair with the then fifty-five year old Lucien Freud, eventually becoming the mother of his son Frank.

Maar was born Henriette Theodora Markovitch to a bourgeois family in Paris, 1907. She became Dora Maar in a decisive act of self-fashioning following her studies at École des Beaux-Arts and Academy Julian, exchanging Henriette for her childhood petname ‘Dora’ and Markovitch for the sleeker ‘Maar.’ Even more so than Paul and Krasner, if not the women of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, her legacy has been a victim of the category of ‘muse’. Her name has been so synonymous with Picasso’s that to see it emblazoned on posters without qualification or addendum carries a subversive charge.

The fascination with the women in the lives of great men is nothing new. The unconventional personal lives of these artists – the string of lovers, each lover representing a phase in the artist’s maturing work, even the historicized cruelty towards those lovers – has all become part of the mythos. There has been some interest in the testimonies of former muses, wives, lovers and daughters of artists, in the hope that they might provide insight into the home lives of geniuses. Françoise Gilot, Maar’s successor, published the mischievous Life with Picasso in 1964 to scandalous success (Picasso estranged himself from Gilot and the children they shared as a result, and the book is currently enjoying a reprint courtesy of the The New York Review of Books.) Picasso’s granddaughter by his first wife, the Ukrainian dancer Olga Khokhlova, authored a damning memoir in 2001 entitled Picasso, My Grandfather, in which she detailed the long shadow Picasso had cast on her family history. Marina Picasso’s memoir belongs to a tradition, like Angelica Bell’s memoir of Bloomsbury, in which the child of artistic milieu wrecks vengeance on the adulation that surrounds their parents and grandparents. They are, in their writings, the casualties of their progenitor’s glamorous carelessness. Their books drive home the uncomfortable truth that a brief sentence in a biography might speak to untold reverberations in a life.

Feminist art history has attempted to pay a slightly different kind of attention to the women in the lives of male artists, hoping to reveal evidence of influence and collaboration, to demystify genius by pointing to its destructive capacity, or remind the world that muses, too, might have made art. The reclamation of these stories is always a delicate task of granting women agency, of considering their artistic output in its own right, while not shying from the seams of darkness that so frequently run through their lives – abuse, violence, madness, and the more subtle, insidious atmosphere of discouragement that faces a woman who wants to be an artist. How do you avoid the pitfall of reaffirming what you are trying to correct, the idea that these women’s lives were defined by the men whose paintings they sat for and whose children they bore? After all, the naysayers argue that if it weren’t for these great men we would not know them at all.

There is always the inherent mysteriousness of art-making itself to contend with, the relationship between the art and the life that can be poured over endlessly while always preserving its slippery unknowability. If Maar’s comment about the light in ‘Guernica’ is illustrative of anything, it is of the difficulties, even impossibilities, in tracing the tangled threads of influence, misattribution and appropriation between two artists who lived and worked in such close proximity.

The Tate’s exhibition is curated both chronologically and thematically. Maar’s career began in the early thirties, as she moved seamlessly from an affluent, cultured upbringing to establishing herself as a successful fashion photographer alongside set-designer Pierre Kéfer. Her studio portraits of the beautiful people of Paris, comprising what she called her “worldly period”, are full of witty surrealist flourishes: a woman stands in the wings of a theatre in a backless evening gown, her face covered by a glittering cardboard star. Maar’s commercial photographs already show what would become a lifelong fascination with the technical workings of the camera and the way the photographic image – still seen as aspiring to truthfulness and accuracy – could be manipulated through techniques such as overexposure and photo-montage.

As the thirties progressed and the political atmosphere in Europe became increasingly urgent and doom-laden, Maar’s attentions turned to street photography. Gone are the beautiful people of the worldly period. Instead, there are photos of pearly kings and lottery ticket sellers in London, blind musicians and children playing on the street in poor areas of Barcelona, and rioters in Paris, snapped quickly with a light, portable Rolleiflex. Maar’s turn to street photography coincided with her involvement with leftist politics. Like several other members of the avant-garde she signed her name to Andre Breton’s Appel à la lutte (Call to the Struggle) denouncing the far-right riots in Paris, and her travels to Spain – then the nexus of the fight against fascism in Europe – were carried out without commission. But it was clear her interests lay in the manipulation, rather than documentation, of reality.

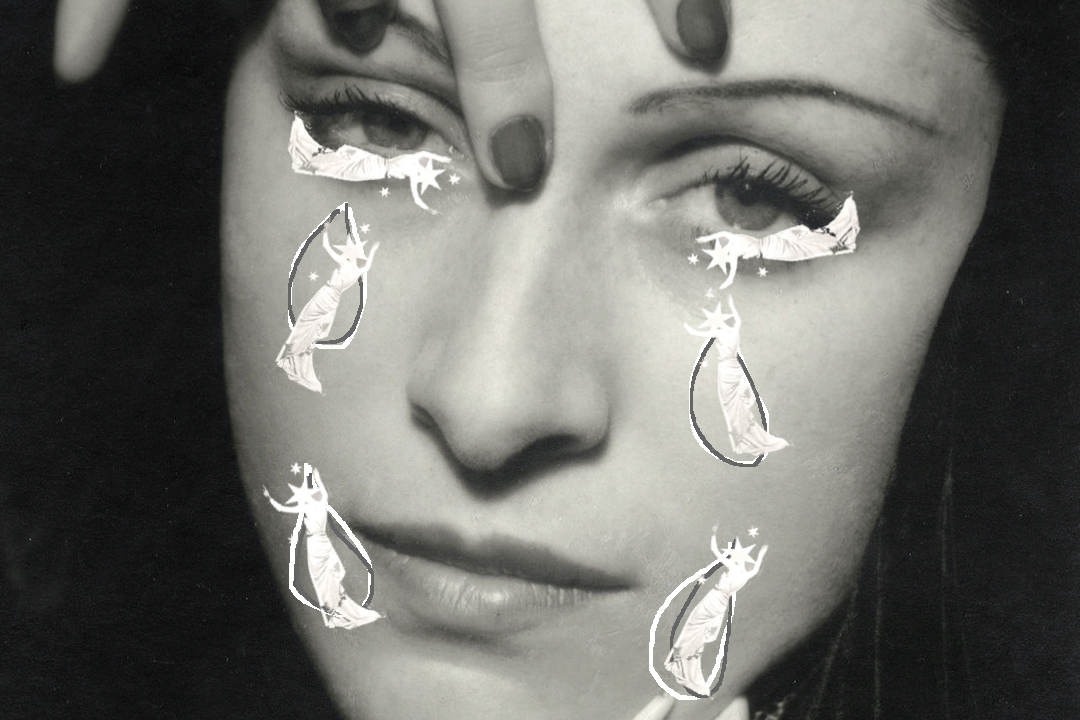

By the late thirties she had wholeheartedly embraced Surrealism. One room of the exhibition is devoted to her role in the network of friendships, rivalries and love affairs that comprised the Surrealist coterie. There is Man Ray’s portrait of Maar (he asked her to be his studio assistant and she declined, saying he could teach her nothing), Maar’s portraits of the poet Paul Éluard and his wife Nusch, an artist and performer, and of the painter and writer Leonor Fini, who said scathingly of Parisian café society that women were expected to do little more than sit and listen. Some of Maar’s most striking images were produced around this time through pioneering photomontage techniques: a woman’s hand, immaculately manicured, curling out of a seashell; a man’s hand pinching a woman’s disembodied legs cut from a fashion advertisement, superimposed onto a photograph of the Seine.

By the time you emerge into the room focusing on her relationship with Picasso, a vision of Maar as a glamorous, prolific, well-connected figure has been established. The Picasso biographical-industrial complex has always figured Maar as the stormy intellectual to Marie-Therese Walter’s placid, unambitious schoolgirl. In this figuration she begins their affair the captivating woman playing a knife game in a Paris café, and winds up a tragic, thwarted figure, just another victim of Picasso’s legendary faithlessness.

Picasso painted Maar weeping thirty-times – a photograph she took shows his paintings of her stacked up en-masse against his studio wall. In ‘The Weeping Woman’ of 1937, her jaunty, fashionable hat sits ironically atop her head, while her face is a jagged morass of grief. In her autobiography, Celia Paul describes how she struggled with sitting naked for Freud, the dispassionate, clinical quality of his gaze making her feel “like I was at a doctors, or in hospital, or in the morgue”, and the sympathy she felt as a result when a life-model in one of her Slade classes broke down weeping because of this feeling of being looked at as an object by the students. Paul’s discussion of how it feels to be painted is interesting for its suggestion that representation is a kind of violence unless treated with a certain sanctity. Perhaps as a response, Paul has said she can only make good paintings of those she loves; many of her subjects are her sisters and her mother, and her depictions of them have the quiet religiosity of an icon painting.

The callousness of male artists to their models is also part of their myth: think of Elizabeth Siddal infamously catching pneumonia in Millais’ bathtub while posing as Ophelia. Indeed, there seems to be truth to the idea that being visually represented as a woman – your face, your body, becoming enshrined in art history – makes people uniquely unequipped to conceive of you as a person, let alone an artist.

Maar seldom sat for Picasso, who stylistically was a very different kind of artist to Freud, and her image seems to have taken on an independent life. She regarded the paintings not as portraits, but as emblems of the suffering of wartime. Her image became that of the calamity of total war, in which the aerial bombardment of civilians collapsed the distinctions between home front and battlefield. The face of war was no longer the soldier on the cenotaph, it was the civilian – the woman or child – whose face was contorted in a collective and instantly recognisable pain.

The war took its toll on Maar, as did private losses, including the death of her father, the disbandment of the pre-war life she had known, and the breakdown of her relationship with Picasso. She lived a long time – until 1997, dying at the age of eighty-nine. She saw almost the whole twentieth-century, survived Picasso by two decades, and kept painting and taking photographs. The final room of the exhibition is a series of Provençal landscapes, starkly removed from the stylised, flattened planes of her initial paintings. After her relationship with Picasso ended – they continued to see each other intermittently after 1943 – she had numerous group and solo exhibitions, spent increasing amounts of time in rural Ménerbes, and returned to Catholicism at the encouragement of Lacan, her psychoanalyst. “After Picasso, only God”, she is reported to have said. It’s an uncomfortable line for someone attempting to give Maar her due place within the canon of the twentieth-century avant-garde, one that gives credence to the idea of Picasso the brand as a dying star that subsumed the lives around it. But there’s something wryly self-mythologising about such a line, too, as though Maar was tossing off something for the biographers. Perhaps more than anything else it testifies to the devotional nature of a creative life: one that endured the vicissitudes of success and publicity, and the peculiar fate of being a muse.∎

Words by Grace Campbell. Art by Chloe Dootson-Graube.