by Hanako Lowry | October 13, 2019

令和 (Reiwa)

In the early hours of 1 April 2019, I was sitting in my bed with my laptop propped open, watching the official livestream of a conference being held in Japan to reveal the name of the coming era. In modern Japan, era names refer to the reigns of certain emperors, which traditionally continue until their death. However, this practice may no longer be so strictly upheld. For the first time since 1817, the Emperor had announced his intention to abdicate due to declining health. Nevertheless, the inextricable link between eras and the lives of emperors persists: the abdicated Emperor will be renamed Emperor Heisei – the era name attributed to his reign – upon his death.

A Kyodo news report on the day of the announcement detailed some of the resistance to the continued use of the era system, with some arguing that it contradicts the post-war Constitution. Much of the resistance comes from those who criticise the original belief that within an era, time is controlled by the reigning emperor. The article reports that on the Wednesday before the announcement, a lawsuit was filed to the Tokyo District Court, arguing that changes to the era name alongside imperial succession restricts individual autonomy and ‘destroys a sense of time held by each individual’.

Before the announcement, I had spent an hour trawling through social media and news websites – enjoying the feeling of participating in an event of historical importance. Still, I wasn’t sure what the new era name could reveal to me about my own future, or even that of Japan. Waves of Heisei nostalgia had dominated media discourse in the lead up to the event, which only served to reinforce the significance that the next era’s name would carry. This historical event, though happening on the other side of the world, would impact my life. When an event is perceived to be of historical importance, it can offer punctuation, exclamation, and form to life. The impression given is that, somehow, I can organise the messiness of life by the terms and frameworks on offer. But what is in a name?

平成(Heisei) and now, 令和 (Reiwa):

I used to think life was like a book: you turn the first page, and there’s the next, and as you go on turning page after page, eventually you reach the last one. But life is nothing like a story in a book. There may be words, and the pages may be numbered, but there is no plot. There may be an ending, but there is no end. (Miri Yu, Tokyo Ueno Station)

How does the relationship between life and written histories play out? It feels difficult – impossible even – to neatly contain all the complexities of a life into a narrative that conforms to ideas of linearity or causality. “Life is nothing like a story in a book,” writes Miri Yu, with life: “there is no end.” In her novel, Yu explores the space between one life and another; she offers an alternative model of history and narrative, a model that allows ‘history’ to be free from the demands of its interrogation. Life and lives are more than personal histories, even collective histories. They cannot be contained within representative models that reply upon linearity, causality. There is no plot.

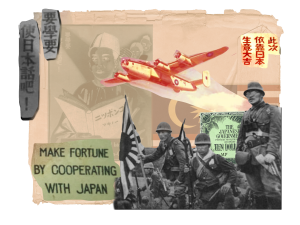

Reiwa, the name of the new era, was given a state-sanctioned translation: ‘beautiful harmony’. The name of a new era is considered vital in shaping expectations of how it will unfold. With Reiwa, many voiced their concern about the potentially authoritarian undertones of the specific selection of kanji characters. The first character ‘令’ (rei) means order or command in its most common readings, whilst the second character ‘和’ (wa) is read as peace or harmony, and is also thought to be the ancient name for Japan. It was also the second character used in the name of the era (Shōwa) that covers Japan’s rising militarism and subsequent defeat in the Second World War. The government have argued that the meaning of the characters must be read in line with the now archaic term ‘令月’ (reigetsu), that was selected from an over 1000-year old poem about plum blossoms, in the Man’yōshū. Selecting the era name from an ancient Japanese poem was a decided break from tradition, as names have been traditionally taken from classical Chinese texts. Interestingly, the Yomiuri Shimbun noted that an era name had been discounted in 1864, as the use of the ‘令’ character could be interpreted as being commanded by the Tokugawa shogunate.

However, for many, exploring the potentially more insidious meanings of the name also serves to hold a mirror to some of the truths of living under the current administration. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe wishes to revise Article 9 of the 1947 constitution, commonly referred to as the ‘peace clause’, in a bid to allow Japan to possess greater military power. Japanese conservatives are also often only too happy to remember the Shōwa era as a time of societal harmony, predicated on greater obedience to the state. Abe’s own comments on the name choice was that it reflects “the spiritual unity of the Japanese people” and he hoped it would become “ deeply rooted in the daily lives of the Japanese people.” Historian Nick Kapur notes that the former comment plays on the second character’s double meaning – as an ancient name for Japan – not found in its use in the Man’yōshū.

In a speech at the British Library’s Japan Now event this year, Yu reflected on the Japanese idiom ‘sweeping the mountains’: the practice of hiding the homeless in Tokyo’s Ueno Park during Imperial family member visits. Yu’s critique functions through her focus on the movement and displacement of people in service of a ‘bigger picture’ of national productivity and progress. Her protagonist is part of the ‘golden egg generation’: originally from the Tōhoku region, brought to Tokyo in the 60s with the promise of employment and a better quality of life, they were discarded once their purpose as manual labourers in the lead up to the 1964 Olympics was fulfilled. Now, with preparations for the 2020 Olympics underway, they have been betrayed again: funds that could have been used to help recovery within the Tōhoku region are being used on a second Olympics and construction companies are going to more extreme lengths in their search for cheap labour to help with reconstruction in Fukushima, due to a labour shortage caused by the monopolising effect of Tokyo 2020. Yu writes her novel to highlight the discord between state narratives of full recovery and optimism and reports of evacuees from Fukushima and the wider Tōhoku region still living in temporary accommodation eight years after the disaster. Revealing 2020 to be far from a ‘recovery Olympics’, the ongoing legacy of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics – the epitome of Showa optimism that the current government seeks to recreate – can in fact be found in the figures of the homeless in Ueno Park, discarded and dislocated by the state.

Alongside preparing for Olympic sporting events, host countries must also look to art and culture as part of the Cultural Olympiad. However an activist group, aptly named the Anti-Cultural Olympiad, have called upon Japanese artists to protest some of the urban development projects that have taken over some central areas in the city. These projects continue to force people out of public housing and generate greater hostility towards the homeless occupying public spaces such as parks in the areas targeted for ‘regeneration’. One protest occurred alongside the painting of murals on erected barriers surrounding development sites in the central Tokyo area; the murals offered narratives about Shibuya, a ward that was highlighted by protestors for the mass clearing-out of the homeless that lived there, as well as the inclusivity and diversity of the individuals comprising its community. Every night (as they were inevitably torn down within a day) activists would attach cardboard cut-out figures to these murals. The figures were there to represent the figures of the homeless that had been evicted from parks, and on their bodies were written slogans calling for the taking back of public space. This direct imposition of the silenced and marginalised figures’ bodies onto these murals created a powerful new visual narrative that attempted to reclaim their right to the city.

Through the voice of the novel’s narrator, Yu similarly rejects common impositions of linearity, progress and completion in her own narrative. Though born the same year as the then-emperor, the protagonist’s life has only been lived in temporal parallel; no other similarity can be found with a life “that had never known struggle, envy or aimlessness”. Drawing on her many conversations with homeless people living in Tokyo, Yu charts an arbitrariness in the way certain frameworks, drawn from and simultaneously reinscribing systems of value, dictate the ways in which lives can and do hold meaning. Under such frameworks, can the life of the protagonist hold value? How can we say that it does, Yu asks, when he must live under the era system whilst simultaneously hiding his existence during imperial visits? Answers to these questions implicate the reader and the ways in which we too seek to articulate time and our lived experiences.

The upcoming Tokyo 2020 Olympics, which will dramatically affect how the beginning of the new era is remembered, claims that it will “enable Japan, now a mature economy, to promote future changes throughout the world, and leave a positive legacy for future generations.” Perhaps complications begin to arise over the government’s stated desire for the 2020 Games to ‘promote future changes’. What will these changes be and how will it affect the lives of the more vulnerable in society? Surely this ‘progress’ will come at a cost. Art in Japan appears necessarily more politicised after the Fukushima nuclear disaster. People see the discrepancies between state narratives of recovery and the hidden truth that lies in the experiences of the displaced, disillusioned inhabitants of Fukushima. It is artists, the Anti-Cultural Olympiad states, that must offer these means through which these alternative narratives can be explored.

Time does not pass.

Time never ends

(Miri Yu, Tokyo Ueno Station)

Yu’s treatment of narrative time, trauma, and memory reveals a disconcerting juxtaposition between the way in which an individual life is lived and narrated, and illustrates how wider superstructures can attempt to erase the truth of individual lived experience. One of the central concepts of the branded vision of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics is ‘Connecting to Tomorrow’. The relocation of the homeless away from public view is just one example of the lack of thought apparent in some of the state’s responses to people’s lives: what is the value of a single life in the face of an event that will instil a vision of national progress and celebration? Yu constructs an alternative, invisible history from the margins of public perception to ensure that some are not forgotten in an overly-optimistic, post-Olympic tomorrow. Yu, herself a representative of and vocal advocate for the rights of Zainichi Koreans, commented on her own marginal status as granting her an access point from which to interrogate and critique the status quo. A state that views any of its citizens as disposable is one that has placed their value in very different, troubling narratives.

In 2015 Miri Yu moved to Fukushima, the reverse of the journey made by individuals at the centre of her inquiry: as construction workers enlisted for projects in the capital, working away from their families for years at a time, or evacuees left homeless following fallout from nuclear plants that supply the whole nation with power. Yu, a Zainichi writer from the Tokyo area, turns her gaze away from the capital and decided instead to shift her focus to the areas that these people were moving from. In Minamisōma, Yu set up a bookstore and a theatre space, and presented a radio programme in which she interviewed individuals affected by the disasters in 2011. Her radio show created a platform for some of these individuals to tell their stories and explore the realities of their own lived experiences. Going one step further than the street art protests in which the silenced and invisible are merely made seen, Yu attempts to make them heard: carving out spaces to facilitate the exchange of different truths outside the arena of a state-issued and state-defined past, present and future. Perhaps it is through literature and art that the history of the new era, Reiwa, can be written as it is lived and felt. By allowing a diversity of voices and of lives to be amplified, we are reminded to shift our focus away from sanitised state narratives of progress to instead try to help those that are suffering now. As her novel’s narrator reminds us, “in this familiar time, there are moments that hurt.”∎

Words by Hanako Lowry. Image from wikicommons.