The Travels of the Bonsai

by Charlotte Slater | April 6, 2023

Towering above the rural village of Maekgwe in South Africa is the King-of-Garatjeke baobab tree. The tree is celebrated for its majestic size and age (some baobabs have reached 5000 years-old), and it functions as a town hall for the local community. The baobab is an iconic symbol of the African savannah, synonymous with its grandeur. And yet, in a Cape Dutch farm on the nearby coast, Bonsai artist Willem Pretorius has been dwarfing baobabs for the last 20 years, taking pride in the fact that he can cultivate mature trees that will only ever reach a few feet in height.

Bonsai is an art form that prompts us to ask why we take joy in miniatures. It seems an odd impulse — to reduce the awe we feel for nature, to domesticate the sublime to what one might refer to as a pet tree. Hugely popular in Japan, where the borders between tectonic plates cause frighteningly regular earthquakes and tsunamis, the Bonsai can seem like a manifestation of the desire for aesthetic control over a hostile landscape. Alternatively, we can read Bonsai as part of a larger dialogue — a mutual exchange between nature and culture, unique in that it is an art form which takes trees as its medium. Caring for a Bonsai tree functions as a microcosm of our relationship with nature and with each other: it miniaturises interactions that also take place on a global scale.

The word Bonsai refers both to the trees themselves and the practice of cultivating them. Bonsai is therefore more than an object: it is a process, an idea which can travel unfettered across the world and throughout cultural consciousness – particularly in literature. In her short poem ‘Bonsai’, the Filipina poet Edith Tiempo suggests that one of the values of miniaturisation is how it makes the unwieldy portable: “something that folds and keeps easy.” For her, this compression is a form of concentration: significance is boiled down, “Till seashells are broken pieces / From God’s own bright teeth, / And life and love are real / Things you can run and / Breathless hand over / To the merest child.” Something that is small and portable, after all, is something that can be shared. It is far easier to carry a pocketbook than a door-stopping tome.

Poetry is no stranger to forms which dare to stop short: on the page, works which operate within restrictive forms are not considered deformed, but informed. The incessant pruning of the Bonsai master is mirrored by the trim pentameter lines of John Philips’s georgic poem, ‘Cyder’. To ensure an apple tree bears fruit, he advises the reader to “Spare not the little Off-springs, if they grow / Redundant.” Pruning, a paradox of tenderness through violence, renders the poem a harvest procured through arduous labour. This is all part of our interventionist stance towards nature. ‘Cyder’ reminds us that in English, the first and principal meaning of culture comes from the cultivation of the land. It only grew to denote the cultivation of the mind or an umbrella term for the arts after the agricultural revolution of the 18th century. Philips’s literary pruning returns the idea of cultivating plants to the idea of culture: cutting a tree becomes a means of artistically refining nature. As ‘Cyder’ demonstrates, the constraint of form often works as a creative impetus, just as the brevity of the human lifespan helps to lend meaning to everyday experience.

The finite forms of life and literature are set in parallel by Alejandro Zambra’s 2008 novella, Bonsai. The Chilean poet tells, with touching concision, the tale of two lovers and a life which stopped short. Zambra gives all this away in the first paragraph, though, ending his synopsis with the grand phrase “the rest is literature”. Perhaps Zambra is not being too bold here: he implies that it is not the mechanical framework of plot which makes literature, but how it unfolds – the process of telling. Inside Zambra’s book, the lovers read a short story which is also called Bonsai, and years later, one of them attempts to rewrite it. This kind of self-reflexivity is dangerous for a novel: Zambra risks overpowering the tenderness of his little narrative with a less appealing sense of his own intellectualism. Luckily, the humour of Zambra’s Bonsai rescues it: the novella always seems to be poking fun at itself, at its own potted reiterations of the now-familiar adage that life resembles a fiction, and that fiction resembles another fiction, too.

When the Bonsai tree makes its way into fiction, it functions in a variety of surprising ways. There always seems to be something unexpected in the interactions between fiction and reality, which objects from real life provide a window into. John Plotz’s study, ‘Portable Property’, is all about the English love of objects: he writes that possessions, in novels and in homes, “generally serve not as static deadweights, but as moving messengers… [they] acquire meaning from their earlier peregrinations.” Jane Eyre, for instance, decorates Moor House with dark mahogany furniture: these unassuming souvenirs of Caribbean plantation slavery act as a direct link to the legacy of colonial cruelty that haunts the entire novel. For Zambra, the scaled-down art of Bonsai works as a model for the metafictional miniatures that mirror his larger narrative. However, as Plotz points out, objects like the Bonsai tree might also function less introspectively, as a connection to the material world outside the text: they trail associational traces of history behind them, marked as they are by their “earlier peregrination”. In the case of the Bonsai, that history is one of travel and cultural interchange. Plotz draws our attention to the contested borders which distinguish cultures from one another. It is no coincidence that the Bonsai tree, with its diminutive size, has become one of Japan’s most iconic cultural exports.

Nowadays, the Bonsai functions almost metonymically in the West as a shorthand for Japanese culture. It is undoubtedly an art that travels well. The first Westerners to discover the Bonsai were taken with these miniature replications of life-like scenes. In the diary she kept during her 1905 stay at the stately home of Count Okuma, Marie Stopes wrote of the Count’s “fine collection of dwarf trees… I watched one of his gardeners pruning a mighty forest of pines three inches high, growing on a headland jutting out to sea in a porcelain dish.” There is an arch amusement in Stopes’s account. The cultivated verisimilitude of the Bonsai landscape must have seemed a world away from material bric-a-brac of the Victorian parlour.

Robert Fortune, a travelling Victorian botanist, described the celebration of “dwarf plants” in China and Japan using similar phrasing to Stopes, reporting that “the art of dwarfing has been brought to a high state of perfection.” Interestingly, Fortune fashions the phrase “dwarf trees” into a verb: “the art of dwarfing.” To ‘dwarf’ typically means to be bigger than, or to make small by comparison – one gets the sense that for the English, “dwarf trees” are all about the human. What does it really mean to dwarf a plant?

The English phrase “dwarf trees” used by these travellers is an imperfect translation of Bonsai. It fails to encompass the process of cultivating and maintaining a Bonsai tree, instead focusing reductively on the product. Bonsai is more than an object, after all – it is an artistic practice, and one which makes use of a living medium. This is another point at which Bonsai overlaps with literature. The medium of language, like a live plant, is never inert. A book is not quite a finished artefact, but a set of ideas reinvigorated with each new reading. Ultimately, Bonsai is a practice that humbles us, rather than engendering total mastery over nature. Consider the shape of a Bonsai artist’s life, structured entirely around the needs of his trees. Who controls whom in this situation? There is an old tale in which a Bonsai master makes his apprentice stand and sweat in the heat of the day to feel as the tree felt when he forgot to water it. It seems that practitioners of the ancient art of Bonsai are doing far more than dwarfing trees: they are rediscovering the ways in which nature and art are intertwined and might be figured as reflections of each other.

Fortune’s intriguing phrase, “the art of dwarfing”, underscores the process by which Bonsai reminds us that size is always relative. Bonsai is not solely a Japanese art, though this is often assumed in the West because Bonsai was first imported to America from Japan, most dramatically after the American occupation of the country at the close of the Second World War. This occupation enabled cultural exchange. General MacArthur held cultural workshops for the American military to enjoy, including ones on Bonsai. The Americans were reportedly impressed by the age of the Bonsai that they were shown, some of which were twice as old as the American nation. In that moment, it may have been hard to tell who was dwarfing whom.

As an art, Bonsai can be a means of reframing our relationship with the world around us – with each other and with nature. Practically, the art of Bonsai makes us more sensitive to the needs of plants, a quality particularly relevant in the period of ecological catastrophe we currently find ourselves in. The theatrics of the famously demanding Bonsai tree also teaches us how fine the balance is between life and death, and how easily human error can kill.

What we discover in the alternative realm of the Bonsai garden can be translated into nature, just as what we discover in literature can be translated into our everyday lives. The history of Bonsai, the globetrotting tree, shows that culture and nature are not at loggerheads. Rather, their interactions can create something beautiful. ∎

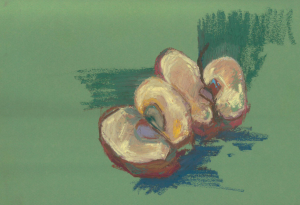

Words by Charlotte Slater. Art by Sophia Howard.