Iphigenia in Jaywick / The Aftermath

by Anna cooper | May 29, 2021

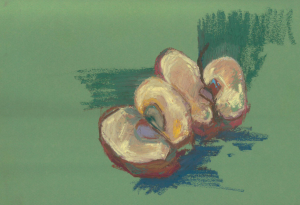

I grew up under stained-glass windows, learnt their blues and pomegranate-reds before my mouth figured out how to form words – I was never good with names, but the faces stuck. One stood looking over the pew our family always sat in, Eve and Adam, her hair the same russet-gold as the apple she held in an outstretched palm. I would sit there every Sunday and wonder if it tasted any different to the apples in my lunchbox, neatly sliced with the grown-up knifes by my mother, who didn’t really understand ‘the whole church thing’ but went along anyway to please my father. She grew up on the outskirts of town, and married the pastor with the hope that he could perhaps be her saviour. And maybe it is a salvation, in a way, to be smiled at and petted and told to be seen and not heard.

It was her who gave me the book, though – a battered old copy that she’d stolen from school at sixteen, a copy I leafed through and spent the rest of the day trying to spell Iliad, Sappho, Iphigenia. The words felt full, foreign on my lips, rounded and warm like honey, dripping off my tongue. I was never good with names, but these ones stuck.

It began slowly. I saw how circles shadowed my mother’s eyes, how her hands shook when we prayed. I had to dig my nails into my palms to stop myself reaching for her across the table, forcing myself to reach the ‘Amen’ as the words slipped, smoke-like, from my mind. I fell a little bit in love with the girl who sat behind me in class — whose perfume tasted like wildflowers and nothing like sin — and used up the whole of the second page of Leviticus drawing her eyes, lips, the line of her neck. The words melted from the pages, running over my fingers in their thousands, but never any with my name attached.

Perhaps I should have admitted it. I could have sat at the dinner table, or perhaps the confessional, said ‘there is never an answer, father, only a void’, and listened to him diagnosing me as too angry, too passionate, brimming with hubris. That may be so, father. But if there is a god, he does not speak to the likes of me. Perhaps it was because, unlike my mother, I was not willing enough to bend. My father believed the holiest thing a woman can be is when it is her upon the altar, but every time I saw my mother’s shaking hands, I wanted to shield her away from the sky and any eyes looking down from above. It has never seemed like a good enough price to pay for a god’s wild whim. I was no Iphigenia — though even she must have screamed, despite what the poets like to say. That was what I thought when I stood in my living room last week, stared at the crucifix over my father’s head as he told me to leave. He did not look at me, only up at the ceiling, as if he could see to some heaven beyond, while I could only see the plaster. There was no more use for me, and a daughter isn’t too heavy a sacrifice to make.

Yesterday was Sunday. I did not go to church. But now I slip out of the afternoon sunlight through great oak doors and find myself under the stained glass. The windows cast a washed-out glimmer on the altar draped in red; I stoop to lie my head across it, cheek against velvet. Then I turn and walk until I stand before Eve. Mother of sin, they call her, those men who clutch at their idols in one hand and pens in the other, all to cross out our mouths. A small sacrifice to offer, they would say, to be meek and mild and utterly unresisting, to pay for her sin which we all carry lodged within us like apple pips. Yet how could Iphigenia have been expected not to resist when their blades were at her throat? I reach up and press my fingers against the cool glass. Mother, be appeased. I think. Forgive, forgive. ∎

Words by Anna Cooper. Art by Natalie Hytiroglou.