Losing Fusun

I can almost never recall my dreams. But last night I dreamt of cycling the US President towards Somerset House.

He wanted to see London, and I wanted to make him feel at home. So, I put some cushions in the back of my rickshaw and rode him to the bank of the Thames. Late at night, we meandered through barely lit streets – me pedalling and panting, him in his huge, beautiful greatcoat, glaring out at the people on the pavements from under the rickety canopy. No one believed it could really be him.

On the way to Somerset House, we got distracted and went in search of a late-night drink. I desperately wanted to please him, but there was only one bar open so late at night. What was worse, the only thing they served were tiny bottles of Leffe Brune, a Belgian beer. Of course, this simply would not do, so I remonstrated with the barman – shouted at him a little and made to pour one of the tiny bottles of Leffe Brune into a glass to show him just how tiny and brown his portions were. But instead of pouring the Leffe Brune into the glass, I poured the brown beer all over my forearms.

I returned to the place where I had left the US President to find him eyeballing the other guests in the late-night bar. I had so desperately wanted to please him with a large portion of English beer, but I came back empty-handed. He didn’t care, though, and abruptly asked me to spend tomorrow night with him. I wasn’t sure whether I wanted that. He had scarcely said a word all night and he was well-known for his passing fancies. Besides, didn’t he have a lot on? Was I really interesting enough to him?

And yet, I also remember contemplating – as much as you can contemplate in a dream – how special it might feel to be with the US President, even just for one night. It had been so very hard cycling him all the way towards Somerset House, and perhaps he had realised just how Herculean an effort I had made to please him. Perhaps he was impressed. I certainly felt admired.

***

We never got to Somerset House. Instead, I woke up at 12.37am with ASMR still hissing out of my earbuds. These had flopped out of my ears as I pedalled in my dream. I had only slept for an hour, which irritated me because I was trying to break my recent sleep pattern of restless nights.

What irritated me even more were the hundreds of flies in my room. I had carelessly left a pot of taramasalata open on my desk. Through the midday heat, it had slowly melted to become a kind of colloid paste, and now the flies – some large, some small – were drowning in pink. I looked on from my bed in disgust.

Sulking over the flies and lost kip, I instinctively reached for my phone. Thirteen days earlier, an old acquaintance had posted something on Twitter about a famous Turkish author called Orhan Pamuk.

My mother read his book to me when I was nine or ten. It was a love story set in Istanbul, where a wealthy, married man falls in love with a shop girl called Füsun. He leaves his marriage and his family behind. But the man soon realises that he will never be with her. He will never be happier than when Füsun and himself made love for the first and only time in 1975. Now, the only things the man can find which bring him close to this fleeting happiness are Füsun and her family’s belongings. He spends three decades gathering these from their estranged home. Each evening he goes across the moody Bosphorus to smuggle the relics in between mouthfuls of dolma, to make his own shrine to the image of a past Füsun, of a previous life. What arises is a museum – Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence.

My mother took an eternity to read the thick book to me. Each night for almost half a year, Füsun filled my mind as I drifted in and out of consciousness. Füsun was never really there, always scarcely out of reach as I skimmed just above a choppy sleep. I never got to see her face.

The closest I came to Füsun was in 2016, when I was able to go to Somerset House to see her belongings. The Museum of Innocence had come to London from Füsun’s family house in Istanbul, which the man bought with his savings to house the museum. You can imagine how long I stood staring at her things. I wanted to inhale them – her silent clocks, her dusty medication, her hairbrushes.

***

A few years later, by some miracle, I found myself at a football match with Orhan Pamuk’s brother, Şevket Pamuk. We ate hotdogs and laughed a lot. Şevket – though nearing 70 at the time – was as boisterous a football fan as any. He spent the entire 90 minutes hurling criticism at the players of both teams, neither of which he supported. He explained his lippiness as a product of his childhood amidst the ritual violence of the fearsome Fenerbahçe-Beşiktaş-Galatasaray love rivalry. His demeanour shocked me. I had imagined Şevket might be a little more like I had imagined his brother Orhan to be – someone who had a way with words and wrote so thoughtfully about the melancholy of love and time.

When Arsenal scored, Şevket leapt out of his seat. Crazy-eyed, he turned to me and gave me a tremendous bear-hug. This was the London he came to see, he told me, as the stadium roared and beer flew through the air. When he sat back down, Şevket’s folding seat trapped my little finger and broke it. I squealed in pain, but thankfully Şevket did not notice, so loud was the din in the stands. I didn’t want him to know – I desperately wanted to impress him and make him feel at home in London.

My hand hung limp by my side for the rest of the football match. Fortunately, I had lost all feeling in my finger. ■

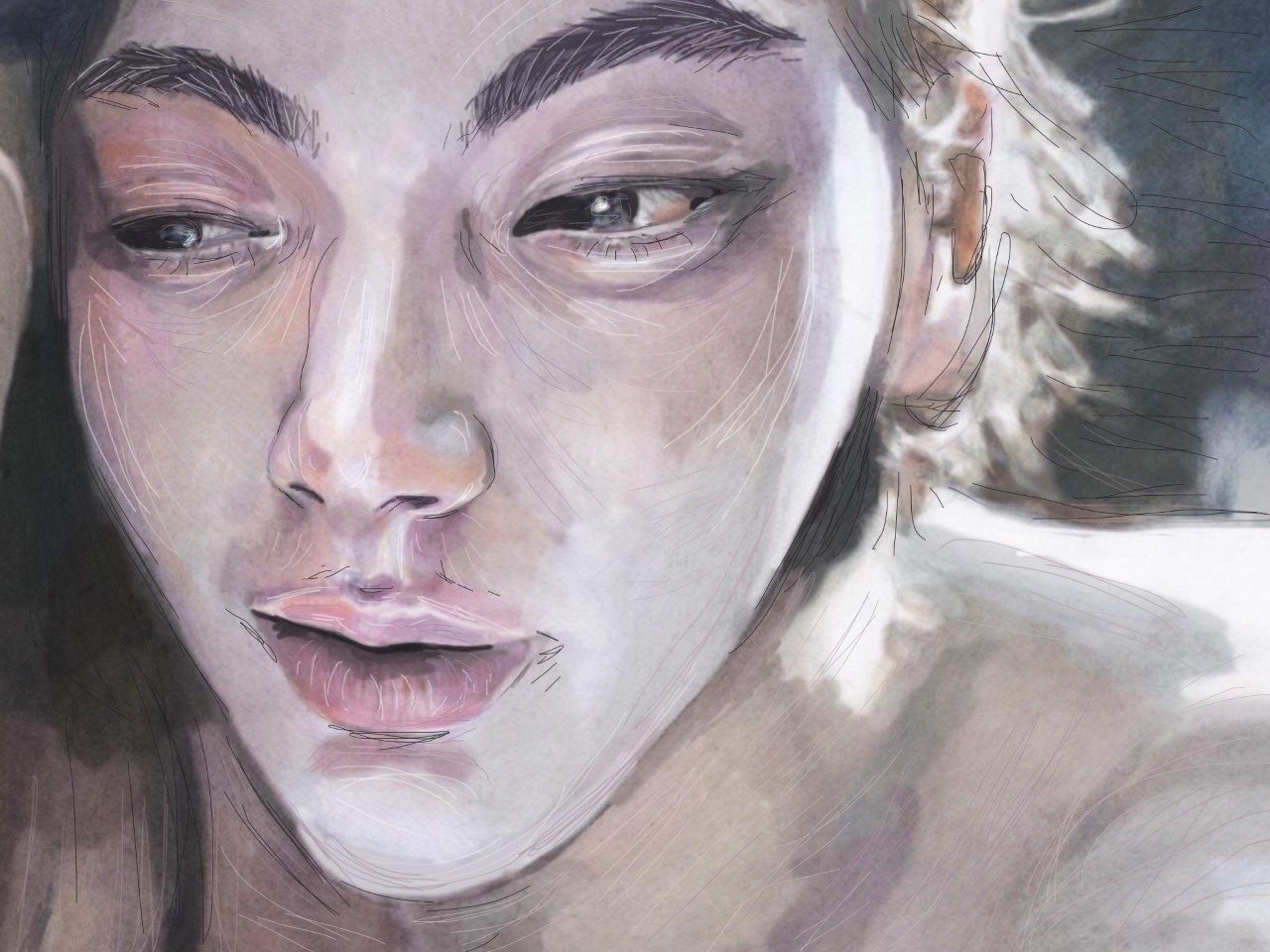

Words by Jorritt Donner-Wittkopf. Art by Holly Anderson.