Too Close for Comfort

by Ben Jacob | September 19, 2019

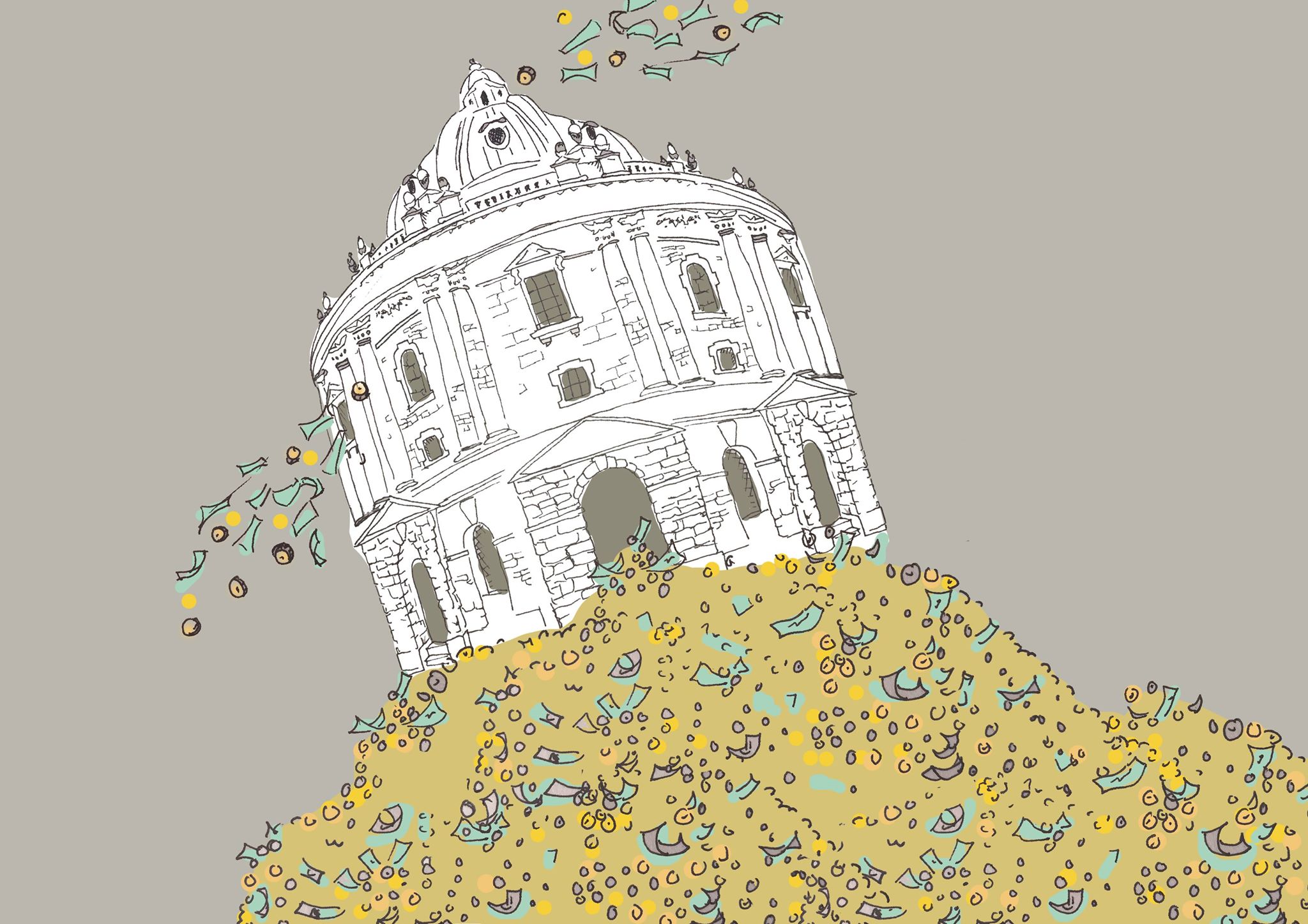

On 19 June 2019, Oxford University Vice-Chancellor Louise Richardson appeared on the Today Programme to proclaim “as good news a story as you are likely to find in a long time.” Earlier that day, Oxford had announced the construction of a new humanities building funded by an “unprecedented”, “transformative” and “enormously generous” £150 million donation from Stephen Schwarzman, the co-founder and CEO of private equity firm Blackstone. The Stephen A. Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities, slated to open in 2022, plans to bring together seven faculties into a single building alongside an AI institute and performance space, and would be among the most ambitious building projects undertaken by the University in modern times. According to the University, the donation will “ensure the place of the humanities in today’s dynamic world”.

Schwarzman, a close friend and advisor to Donald Trump whose lavish lifestyle and aggressive business practices won him the moniker “the designated villain of an era on Wall Street”, has seen previous donations to universities met with hostility on campus. At MIT, the announcement of a $350 million Stephen Schwarzman Centre of Computing ignited protests from faculty members and students labelling Schwarzman a “human rights violator” and a “slumlord”. At Yale, senior university officials grilled reporters at the student newspaper Yale Daily News over their investigations into Schwarzman’s donations and business practices following the $150 million remake of the university’s Commons building into the Stephen A. Schwarzman Center.

Oxford’s plans for the Schwarzman Centre were barely discussed within colleges. The plans, first proposed over a decade ago, and negotiated with Schwarzman over a three-year period, were announced three days before the end of the academic year, when most students were sitting exams. This meant that initial open meetings for consultation took place in July, when students and many faculty members are typically out of the city. An exhibition to view the plans drawn up by the shortlisted architects on 16 September was treated as invite-only and “confidential”, exemplifying a lack of transparency that extends across the process. The negotiations with Schwarzman are now subject to a Non-Disclosure Agreement, while the University has refused requests to publish details of its ethical review process surrounding the donation.

This week, an open letter was published opposing the University’s decision to accept Schwarzman’s donation. The letter, signed by a number of academics, local councillors, student groups and community groups, argues that the ‘Schwarzman Centre’ will be “built with the proceeds of the exploitation and disenfranchisement of vulnerable people across the world”. It calls for “new transparent and democratic procedures” regarding donations, stating that, without “full details” of how the decision was made to accept Schwarzman’s money, the University risks “significant” future damage to its reputation.

Exactly twelve years before Oxford announced the donation, Blackstone went public. By the end of that same day, Schwarzman had made $677 million from selling shares and the company had been valued at $31 billion, with Schwarzman retaining additional shares worth $7.8 billion. Private equity – money invested outside of the public market – has enjoyed a golden age over the last forty years, with the total value of private equity buyouts rising from $28 billion in 2000 to $582 billion in 2018. Founded in 1985 by Schwarzman and Peter Peterson, Blackstone has stood at the forefront of this growth.

Central to this success has been the leveraged buyout, as pioneered at Blackstone. In this takeover model, a publicly traded company is acquired by the private equity firm. The acquired company is then managed aggressively by cutting costs and boosting cash flow, before being sold on after a period of five to seven years. The power of this model lies in its use of leverage, or borrowed money, to increase returns: the buyout and financial restructuring is funded with large amounts of borrowed money, which the acquired company is forced to pay off prior to its resale. In this arrangement, the private equity firm stands to make a huge return on its initial investment. In contrast, the acquired company, writes financial reporter Josh Kosman, is left with “enormous debt and falling earnings”.

This high-profit model has driven private equity, which benefits from looser regulations and lower taxation than public companies, to a position of enormous influence in the global economy. In the best instances, private equity’s large investment funds and its freedom from regulations allow it to support enterprises that could not attract funding from traditional lenders. Its ability to provide the investment needed to survive has saved countless companies from closure. Celtel – one of several African companies that spread mobile telephony all over Africa – depended on the contribution of private equity companies.

The focus on short-term profits over long-term health, however, makes it a controversial practice in the eyes of some. Where traditional banks have an interest in the longevity of their investments, private equity firms are defined by short-term profits. As sociologist Saskia Sassen argues in forthcoming documentary Push, “once it has extracted what it needs, it doesn’t care what happens to the rest”. For shareholders and their beneficiaries, such as Oxford University, this model provides great returns. For less fortunate players in the global economy, however, the impact of private equity can be highly destructive.

Buy it. Fix it. Sell it.

“The real golden age”, Stephen Schwarzman told Robert Peston in a 2008 interview, “comes when you have a mess. You have economies that are on their back.” As Joseph Stiglitz states in Push, Blackstone were “the big winners of the financial crisis in the housing market”. When the US government forced foreclosures on single-family homes to clean up the books, Blackstone saw an opportunity, buying distressed assets in neighbourhoods with good schools, transportation systems and jobs, and renting them out. Today, Blackstone’s real estate arm owns more property than any other landowner on the planet, with $154 billion in real estate assets including 296,000 residential units and homes.

“The strategy is very simple”, explains Jon Gray, Global Head of Blackstone Real Estate, “we call it ‘Buy It, Fix it, Sell it’.” “We acquire assets at discounts”, touts the Blackstone website, before “unlocking value” through “aggressive asset management” and then “returning capital to our investors”.

Blackstone maintains that its real estate interests are crucial to alleviating the chronic undersupply of housing. In communications with The Isis, the firm noted that it brings valuable capital and expertise to the sector, while adhering to local housing laws, improving its houses through renovation and spurring economic growth in local areas.

However, Wall Street’s push into the housing market has drawn criticism from affordable-housing advocates, who argue that the value it provides to shareholders comes at the cost of its tenants. Earlier this year, UN Special Rapporteur Leilani Farha published a report accusing Schwarzman of violating human rights through the “financialization of housing”, with a “grave impact on the right to adequate housing for millions of people around the world”. Farha’s report echoed findings by an investigation by Reuters in 2018 into Invitation Homes – a Blackstone creation that grew to prominence in the single-family rental market after the 2008 crash – which found complaints from Invitation tenants of toxic mould, leaks and black widow spider infestations, with some alleging that they are victims of excessive and illegal late payment fees.

Blackstone has defended itself against Farha’s allegations in a public response citing “significant factual errors and inaccurate conclusions”. The letter maintains that Blackstone “hold ourselves to the highest standards of fairness, transparency and empathy for our residents”. It also insists that Invitation Homes is “in the business of housing families; eviction is never a course they want to pursue.”

Wherever Blackstone have invested in social housing, anxieties nonetheless continue over the suitability of the private equity giant to responsibly house vulnerable people. René Christian Moya, director of housing advocacy group Housing Is A Human Right, stressed to The Isis that Blackstone has played a significant role in a crisis of “unaffordable housing costs, an evictions epidemic and skyrocketing homelessness”. Moya also pointed to Blackstone and its affiliates’ contribution of over $6.8 million to a campaign against rent controls in California, where Invitation Homes own around 13,000 rental homes (Blackstone has defended this donation, suggesting that rent controls would have discouraged new construction and investment in affordable housing).

15 Gregory Place, Witney, 10 miles from the site of the proposed Schwarzman Centre, now stands at the centre of debates over Blackstone’s role as a provider of affordable housing. In December 2017, the private equity firm bought a 90 percent stake in Sage Housing, a for-profit UK social housing provider with a 7000-home portfolio including 15 Gregory Place. With 20,000 homes due to be built by 2022, Blackstone stands to become one of the largest providers of social housing in the UK, two years before the Stephen A. Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities is due to open.

A global reach

Debate over the long-term implications of Schwarzman’s activities is not limited to real estate. It is perhaps most marked in his activities in the energy sector. As revealed in a 2017 report by DeSmog, Blackstone has $7 billion invested in oil and gas, with a financial stake in every sector of the industry. Schwarzman has bought interests in drilling fields, fracking companies, major pipeline projects and power plants, with multiple stakes in projects that have fallen foul of environmental observers. With Schwarzman’s pay package coming largely in the shape of stock dividends, his wealth, and thus the capital for the new humanities centre, is linked directly to these ventures.

In recent weeks, Schwarzman’s activities in Brazil have been identified by The Intercept as a “driving force behind Amazon deforestation”. The Intercept allege that Hidrovias do Brasil and Pátria Investimentos, two Blackstone companies, have deforested land to develop a highway to their new shipping terminal at Miritituba in the Amazon, from which grain and soybeans can be readily exported. The highway, B.R.-163, has been linked to the destruction of the Amazon, both by increasing deforestation in large areas around the highway, and through enabling the transformation of the rainforest into a source of agribusiness revenue.

Blackstone maintains that it neither owns nor holds a stake in B.R.-163, and has described the claims made by The Intercept as “blatantly wrong and irresponsible”. The company’s statement stresses that Hidrovias possesses multiple awards and certifications for its environmental and sustainability standards, while the shipping terminal at Miritituba plays an “important role in reducing carbon emissions” by shifting traffic from the roads to the waterways.

While Hidrovias possesses the official certificates, the picture that emerges from its World Bank-IFC evaluation offers a far more ambiguous picture than that offered by Blackstone. The IFC report does state that river transport is a “safe and environment-friendly means of transport” that generates “comparatively fewer emissions than other more conventional methods of freight transport”. However, the report counters this by explaining that Hidrovias’ development of Miritituba port, close to intact areas of the Amazon, is likely to “accelerate conversion of natural habitats into agricultural areas”. Indeed, less than one month ago, as media outlets began reporting on Brazil’s wildfires, Hidrovias announced plans to double its grain shipping capacity to 13 million tonnes.

When the allegations put forward by DeSmog and The Intercept were raised to a Blackstone spokesperson, they told The Isis: “Responsible and sustainable investing is a central element of the firm’s culture and is reflected in the work that we do. From the day of our founding, Blackstone has dedicated itself to being a responsible corporate citizen. Our commitment to corporate responsibility is embedded into every investment decision we make.”

Weaponising philanthropy

Blackstone’s ventures have nonetheless profited from Schwarzman’s close relationship with Donald Trump. Trump’s plans to “unleash America’s untapped shale, oil, and natural gas reserves” have coincided with Blackstone’s expansion of its oil and gas investments, with pipelines and fracking ventures given the green light after years of delay under the Obama administration. Described by The New York Times as “one of the president’s most respected and reliable allies in high finance”, Schwarzman has stood by Donald Trump through every controversy of his presidency. Appointed as chair of Trump’s Strategic Policy Forum in December 2016, he stood by the president when the forum disintegrated after the president’s Charlottesville remarks, commenting only that he “wasn’t outraged”. According to Politico reports, Schwarzman spoke with Trump at least once a week at the height of his influence, advising the president on matters ranging from the economy to foreign policy and immigration, at a time when White House policies included the Muslim Travel Ban and withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Schwarzman’s relationship with the American right has its roots in the same kind of “enormously generous” donations that Oxford announced in June. As Jane Meyer’s Dark Money details, Schwarzman is part of a network of billionaires who have bankrolled a “systematic, step-by-step plan to fundamentally alter the American political system”. Led by Charles Koch and his late brother David, this circle of wealthy allies with libertarian views organised their vast resources to create organisations that could influence and control academic institutions, think tanks, courts, and high politics. Schwarzman entered this network in 2010 in response to the Obama administration’s attempts to close the private equity tax loophole from which Blackstone profited handsomely. Describing the plans as “like when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939”, Schwarzman was drawn to the biannual summits hosted by the Kochs, where his wealth, along with other plutocrats angered by Obama’s plans, provided what Meyer calls a “raging river of cash capable of carrying the whole Republican Party to the right”.

Donations such as that received by Oxford are essential to these activities. As Meyer writes, the Koch circle saw that their political activities could be presented as tax-deductible ‘philanthropy’, with funding sources allegedly hidden wherever possible and political organisations given innocuous names. “Weaponising philanthropy”, the circle used their reputations as charitable donors to influence American politics in favour of the far right. Donations to prominent cultural and scientific institutions such as the Lincoln Center and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center won David Koch a reputation as a respectable philanthropist at the same time that he was building an ideological machine to allow America’s wealthiest families to influence the country’s politics. Similarly, Schwarzman’s political fundraising has grown in the last decade alongside his philanthropic activities. His emphasis on name recognition is well known. Schwarzman once walked away from a $125 million donation to Yale because it refused to name a building after a living donor, while the initial agreement for a $25 million donation to his high school – rewritten under pressure from parents – called for the school to be renamed and for a portrait of Schwarzman to be displayed “prominently” within the school.

Competing globally

Oxford University’s spokesperson noted that Schwarzman’s donation had been approved by Oxford’s “rigorous due diligence procedures which consider ethical, legal, financial and reputation issues.” They emphasised that the idea of a humanities building had been discussed for over a decade before Schwarzman provided the funding for the building. “We had to maintain confidentiality about the donation until it was approved and signed.”

The donation was referred to the University’s Committee to Review Donations and Research Funding, which considers matters that “raise issues of a reputation, ethical or similar nature” regarding donations. It seems likely that the Committee to Review Donations, which approved Schwarzman’s donation, considered Schwarzman’s political donations and the debated global reputation of Blackstone’s activities. However, Oxford has refused requests to disclose the committee’s findings in order to protect the University’s “commercial interests”. Beyond its referral to the committee, there has been no other internal consultation regarding the potential reputational cost of accepting Schwarzman’s donation, and faculty members were not consulted until after the Schwarzman Centre was announced.

The risks attached to accepting large donations from donors with controversial reputations are only set to increase. The EU is responsible for over half of the external research funding for several Oxford departments, while many of the humanities faculties are set to lose over a quarter of their funding with the loss of EU research grants. As a result of Brexit, the University will become increasingly dependent on private donations such as Schwarzman’s. Defending the University’s decision to accept Schwarzman’s donation, Louise Richardson told the Today Programme, “if we want to compete globally, we will have to engage more in philanthropy.”

Refusing scrutiny and transparency regarding donations in order to “compete” with other institutions can be dangerous. The American colleges with whom the Vice-Chancellor wants to compete offer a stark lesson for Oxford’s management. Two weeks ago, MIT Media Lab’s decision to take anonymous donations from the financier and paedophile Jeffrey Epstein led to the resignation of its director Joi Ito. Ito was revealed by The New Yorker to have taken measures to ensure that Epstein’s donations did not come to light in order to avoid accountability and transparency. These actions had consequences: as the New Yorker reported, “Epstein used the status and prestige afforded him by his relationships with elite institutions to shield himself from accountability.” In an internal letter, MIT President Rafael Reif wrote that gifts such as Epstein’s were “always subject to longstanding processes and principles.” Like Oxford’s Committee to Review Donations and Research Funding, these were not accountable to University members.

Stephen Schwarzman is not Jeffrey Epstein. But for those concerned by transparency in cases such as Schwarzman’s, the Epstein case demonstrates the dangers of prestigious educational institutions refusing accountability in order to gain a competitive edge. Harvard law professor Larry Lessig, in a defence of Ito, blamed the scandal on the pressures of raising money for research in a competitive funding environment. “I thank god”, wrote Lessig, “that I’ve never been obligated to raise money for an institution like MIT.” Similarly, requests to publish the findings of Oxford’s Committee to Review Donations have been refused on the basis that doing so would “deter prospective donors”. In a letter explaining this refusal, the Information Commissioner Max Todd argued that “the University competes for funds with comparable institutions … disclosure would place the University at a disadvantage in comparison with these institutions.”

Asked on the Today Programme whether Oxford’s ties to controversial donors made her “wince”, Vice-Chancellor Louise Richardson replied, “I focus on the things that these gifts are going to enable.”

However, in light of stories emerging concerning the Sackler family and Epstein in particular, the conversation around donations is shifting away from commercial interests towards ethical considerations. In March, the National Portrait Gallery announced that it was giving up a £1 million donation from the Sacklers amid controversy over their role in producing the drugs that have fuelled the opioid epidemic in the US. Other such decisions have since followed from the Tate galleries, the Met museum and the Guggenheim. The demands in the Schwarzman open letter for transparency and due diligence around donations have been echoed across the media in recent months. An opinion piece in The Financial Times last week argued that universities must be “more disciplined and more open” in judging whose money to take, while an article published in The Wire yesterday described the system for processing philanthropic gifts into academic research as “essentially a pool of dark money”. In The New York Times, Farhad Manjoo argued that Epstein’s donation suggests “a deeper and more intractable moral rot … when a billionaire comes calling, men in the ivory tower can’t resist lowering their golden locks to let the plutocrat climb aboard”.

For René Christian Moya of Housing Is A Human Right, the Schwarzman centre is a direct attempt to “rehab” his global reputation by “buying some of Oxford’s prestigious reputation through his contribution to the university”. The signatories of this week’s open letter demand “critical examination” of the donation, accusing the University of “disregarding” Schwarzman’s record.

But, as Vice-Chancellor Richardson told the Today programme, “do you really think we should turn down the biggest gift in modern times?”

Words by Ben Jacob. Ben is a member of Common Ground Collective, one of the signatories of the open letter mentioned above. Artwork by Ellen Sharman.∎