Oxford joins the UCU strikes

by Poppy Sowerby | November 26, 2019

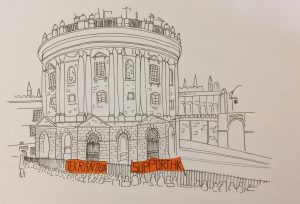

Large crowds gather outside the Clarendon building on a cold Broad Street, sporting heavy coats and bold slogans. These are protesters, clustered in the rain to kick off eight days of strike action over the pay and teaching conditions of academic staff. Nationwide, sixty universities are participating in the UCU-organised resistance, aiming to collectively address the union’s concerns: workloads going up, salaries going down and pay gaps among women and minorities refusing to disappear. Students bristle among the staff, craning their necks to see speaker upon speaker emerge from the huddle at the top of the steps. There are boos, there are songs; the usual start-of-the-week inertia has been replaced by something different.

The speakers draw loud hisses with their statistics: heads shake at mentions of the casualisation of labour, the ever-growing commercialism of higher education. Marina Lambrakis of the Oxford UCU committee tells us that 80 per cent of staff at the University are on casual or precarious contracts. Elsewhere, speakers decry the misconception that the gig economy ‘only affects low-wage workers.’ Among the speakers is Hugo Raine, an Oxford student and organising activist. Raine compares students to ‘customers buying a commodity’: for him, universities have become ‘shops’, and staff are suffering as a result. “The University is an immensely unequal space,” he tells me. “We have the Vice Chancellor and a small group of older, almost exclusively white male academics who’ve been here for a long time – but most of our tutors are on one-year contracts, or even rolling term ones. Many of our staff are PhD candidates who are only paid if students take their papers. It’s a disgraceful situation.” Student involvement with university strikes are always fraught with those demanding to ‘get what we pay for.’ To the protesters, however, such complaints do not compare to systemic problems staff continue to face. Student concerns are intimately tied to those of workers on uncertain contracts, Raine tells me: “Every time our rent goes up, every time our fees go up, that’s accelerating the process [of commodifying education]. Every time students are attacked, it is those precarious staff that are also attacked. The only way we can win is to fight together.”

Other onlookers agree: these eight days of striking are bound up in the broader cause of workers’ rights. For most here, the inconvenience of lecture cancellations and reduced library access pales in comparison to such concerns. “Deciding to show solidarity is a personal choice,” according to Callum Voge, a public policy student at the University. He’s concerned about the impact on students from abroad – and understands why some might be more inclined to cross the picket lines. “At [St Cross college], we have a lot of international students who have scholarships, so their Visas and scholarship money are at risk if they participate.” Later, I encounter Angela Boyle and Matthias Barker from the Oxford Living Wage campaign, and Philomena Wills from Oxford Migrant Solidarity. For them, the issue of international students facing consequences for backing the strikes is also urgent. The three refer to a recent incident at Liverpool University, in which students with Tier 4 Visas were sent an official email informing them that if they chose to strike, they could risk jeopardising their Visa status. For Wills, this amounts to “threatening already marginalised migrant groups and preventing them from striking.” For Boyle: “migrant justice is worker justice, and vice versa.” I ask if the intensity of the student divide might alienate some from participating: Barker encourages students to “direct your anger at the university authorities, not your lecturers.” These protesters believe that media narratives encouraging disgruntlement are part of a broader tactic of ‘separating students from workers’ – however, as Boyle points out: “our interests align, because their teaching conditions are our learning conditions, and our future working conditions.”

For those on the Oxford Living Campaign committee, the issue is closer to home than some might realise. Barker tells me that at his own college – St. Anne’s– it was revealed that the student levy (intended to ensure staff meet the living wage) was ambiguously branded so that while students believed they were paying to meet the Oxford Living Wage for holiday and conference workers, the figure was stated as £9 per hour on the official levy sheet. The Oxford wage is £9.62, and so the wage stated on the original levy is, Barker states, ‘a poverty wage’. There is a broad sense of suspicion over what exactly is being done at the University to implement proper pay for staff. For Raine, the discrepancy is a disgrace: “in the last nine years, when tuition fees were trebled, the pay of Vice Chancellors across the country has gone up by 200 per cent.” Barker raises the recent £150 million donation by Stephen Schwarzman to the University and mentions the scale of endowment sources: “there’s literally no reason they can’t pay.” When I briefly mention the expense of the tutorial system, Boyle is frank: “it’s a cost of doing business. You can’t get away with exploiting people and so it doesn’t matter if it’s expensive. You can’t deny people a decent life and dignity.”

For both staff and students protesting, university administration has misled and mishandled the issue of employee treatment. In the crowd, there is no uncertainty about the ethics of striking: in order to be heard, academic and non-academic need student backing, as all workers should be able to. In any case, at Oxford we feel the effects less than elsewhere. As Wills points out: “at universities without college systems, when there’s a strike, you have no teaching and you have no libraries.” The protests are due to end on 4 December – until then, picketers will be dotted around the city. As the demonstrators scatter from the Clarendon steps, an air of optimism persists.∎

Words by Poppy Sowerby. Photography by UCU Left.