Letter from the Marquesas

by Holly Fairgrieve | November 11, 2018

We board a tiny plane to Hiva Oa at dawn.

An old fisherman sits next to me on the flight. He speaks in rapid, broken French whilst brandishing a photograph of his prize catch. Out of the window, I watch the land heave up in peaks then sink into valleys, falling in cliffs and buttresses. There are no lights, no smoke, no towns – no sign of people at all. The mountains are feathered with clouds and the old fisherman laughs as we bounce up and down in the turbulence.

When we arrive at Hiva Oa, crowds of families – all women and children – thread their way through the passengers with piles of pandanus, leis and flower crowns. Two women greet us, smiling with their cigarettes in their mouths as they introduce themselves. Then we’re loaded into a pick-up truck, carefully keeping our legs raised to avoid both the hot leather seats and the large gun underneath them. We’re transferred into a lone blue fishing boat at the dock; enclosed by cases of soda which are loaded in great piles after us. After an hour of being tossed on the high seas, Tahuata finally comes into view.

Tahuata is the smallest island inhabited in the Marquesas archipelago of French Polynesia. It is roughly one fifth the size of the Isle of Wight and its main village, Vaitahu, has a documented population of just under 100 people who speak Marquesan and a dialect of French. The island was not known to Europeans until Captain Cook landed there in 1772. Thereafter it became a major stopping point for all European trading ships which sailed around the bottom-most tip of South America.

I’m here to spend the summer working on a community-based archaeology project led by the US-based Andover Foundation for Archaeological Research. This kind of archaeology prioritises local involvement (our team is majority Marquesan). Me and two other foreign students help Professor Rolett, alongside Marquesas natives Manuhi, Fati, Hio, Joseph and Sam.

Natural resources are abundant in Tahuata: The forests are full of Tahitian chestnut trees and coconut palms, which serve as building materials. Fruit trees ache with breadfruit, star fruit, mangos, banana noni, guavas, coconuts, pomplemousse, oranges, lemons and limes. The ocean provides fish, lobster and shark. There are very few roads and even fewer street lamps.

The land is untamed, volcanic and mountainous, with vast undulating valleys. Daylight plunges into the dark forest thickets and disappears. Clouds form around the high peaks, creating green Olympuses, then deepen and burst with dense, sweet warm rain. The showers evaporate fast in the heat and take with them the scent of the hibiscus flowers and wild basil. A perfumed humidity is left in their wake.

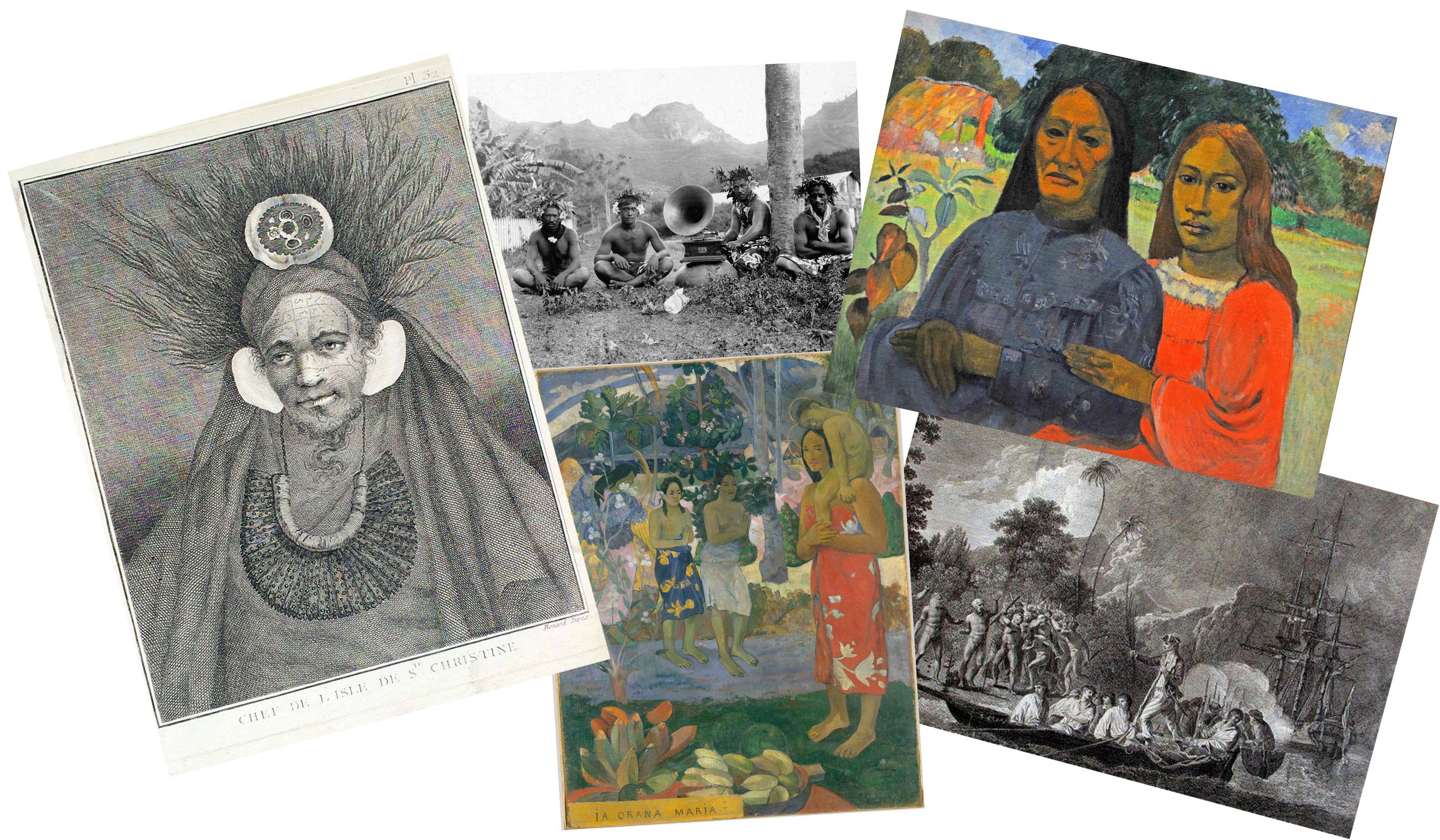

The landscape here has long provided inspiration to foreign writers and artists. Robert Louis Stevenson arrived with his wife in 1888, looking to a more temperate climate for a cure for his sickness. Instead, he found inspiration for Treasure Island. Perhaps most famously, Paul Gauguin arrived in 1901 and depicted the Marquesans in his paintings and sculptures – characterised by exaggerated body proportions, animal totems, geometric designs and stark colour contrasts. For such a small and remote place, it is astounding what a large imprint the Marquesas have had on the western imagination. According to Stevenson, “No part of the world exerts the same attractive power upon the visitor”

During our first week, our team is invited to the waterfront home of Felix Barsinas, the Mayor of Tahuata. Felix’s wife, Jeanne Marie welcomes us and presents us with flat baked discs of grated chestnut and coconut glued together with sugar. The mayor excitedly tells us he has been invited to Paris to meet with the French government to discuss his long-term hopes for Marquesan independence. He has been vocal in his determination to shake loose the grip of foreign powers and foreign values on his village and expresses his anger at the French authorities’ lack of regard for his own culture and people. The mayor’s sadness is most palpable when he explains that for the first time younger children are speaking exclusively French to each other. During his childhood, French was only spoken in the classroom and the church. It was Marquesan with your friends; Marquesan at home.

We are asked how our excavation is going and I explain that we found a human tooth that day; a large white molar. It was found in a refuse pit from an umu earth oven and initial investigation suggests it was the product of cannibalistic activity. The Barsinas become awkward and quiet at this news and it takes a few minutes for the conversation to recover. It’s very clear that I have made a mistake in mentioning the tooth and yet I’m not sure why.

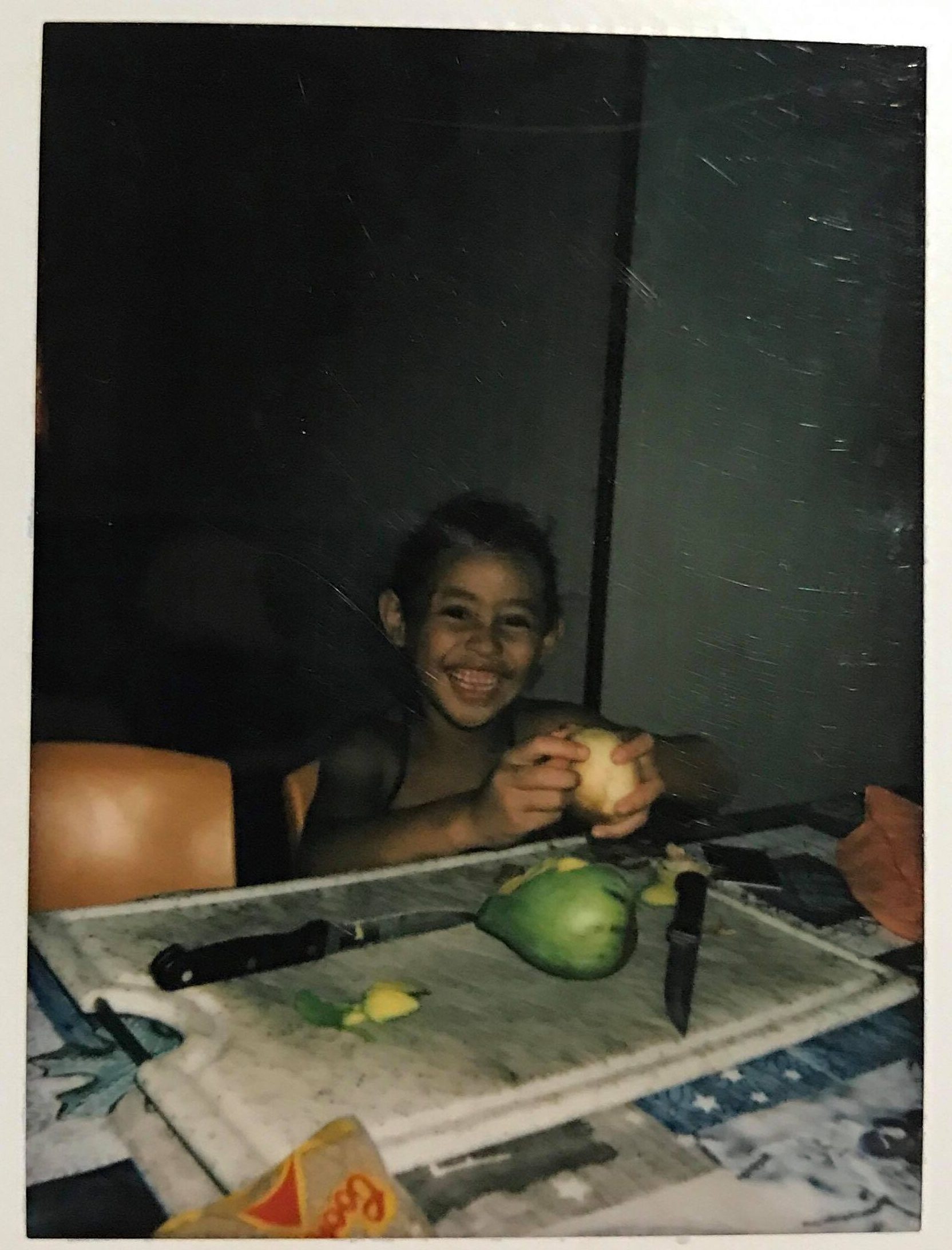

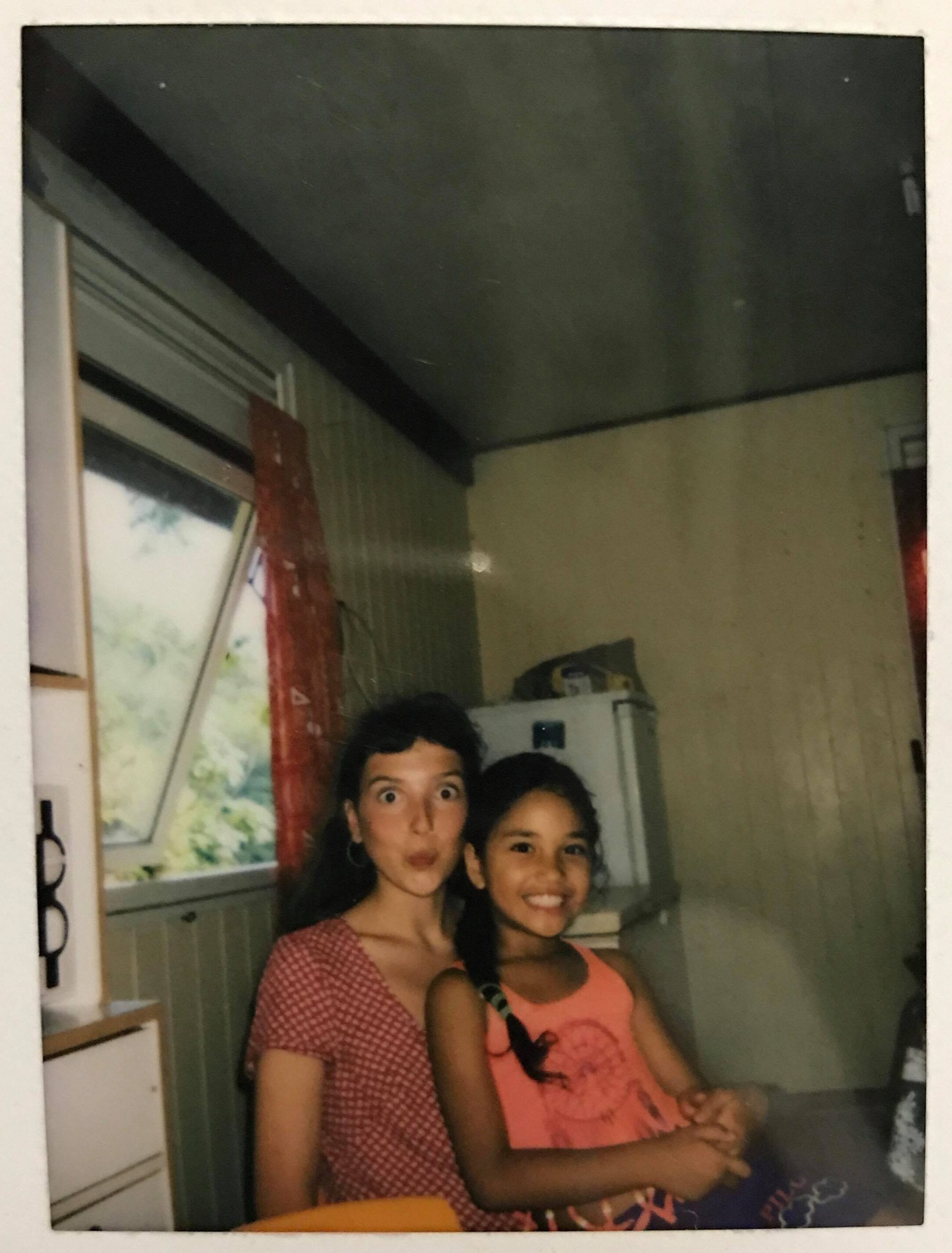

Days digging in the sand dunes leave me salty with sweat, sticky with mango juice and caked in dirt. I make my way to the beach where the children are playing. They run in the sand, gather speed, and then throw themselves into the high waves, quickly reappearing on the crests of the surf, bouncing around like buoys. It is here that I meet Maheni, the daughter of one of the men on the dig, who will become my little companion, ta’u tuehine tafai (my adopted sister).

When Maheni decides it is time for us to leave, all the children follow. She beckons at me come too, so I am led by the gaggle of children to Jimmy’s house. The plan, I learn, is to get food.

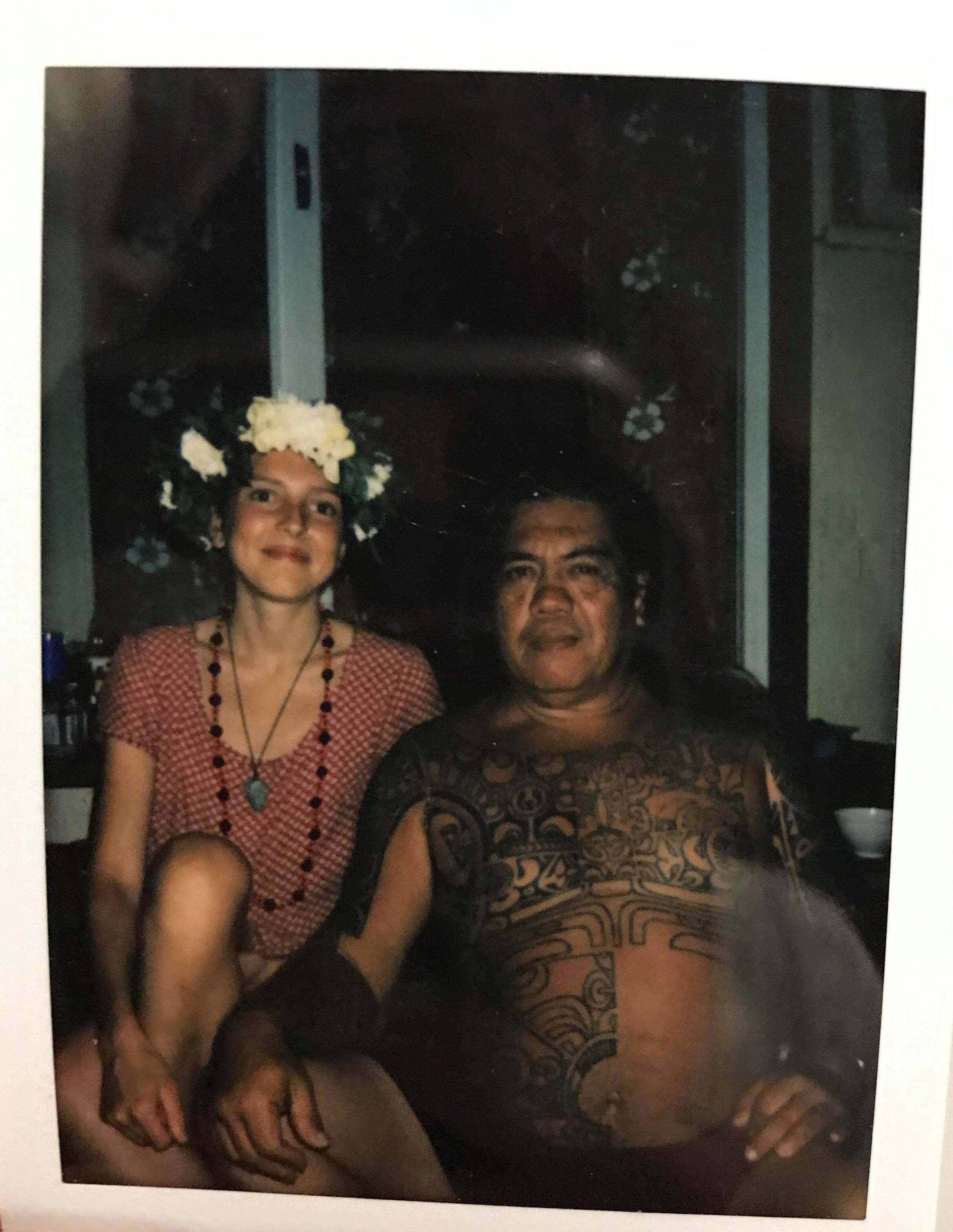

Jimmy is a large man. They call him Chez Jimmy as his house doubles as a sort of cafe. People come and pay him for the dishes he makes — he is a fantastic cook. Our little squadron walks in and we nearly fall over him lying prostrate on the floor, face down, his flat belly spread by the force of his body weight against the wooden floor. He is snoring, loudly.

The children laugh, prodding and poking him, then run away as he starts to wave his hands around, as if swatting away a fly. I am left alone, apologizing profusely. He laughs, rolls himself over, shakes my hand and introduces himself. We sit outside for the rest of the evening, talking and eating. The conversation centres on spirituality and Marquesan beliefs about the supernatural. Jimmy explains to me why my mention of the tooth at the mayor’s house had so disrupted the evening.

Marquesan spirituality dictates that people are to be afraid of “tapu” objects — objects that belong to the past world of their ancestors. This is because they possess a supernatural power called “mana”. Touching, removing, or interfering with these objects disturbs their mana and risks bringing the curse of misfortune and sickness to the family.

Marquesans are acutely aware of this belief at this time of year because it is Tahitian chestnut season. To harvest these chestnuts, one has to venture to the back of the valley on Tahuata, where the old paepae lie. These are the foundations of roads, houses and ceremonial buildings that were occupied by over a thousand Marquesan chiefdoms which were obliterated after European contact. The Marquesans suffered terribly at the hands of the French, and their population collapsed from 45,000 to only 3,000 in the early 1900s. Anyone collecting chestnuts at the back of the valley has to be careful as they often stumble across carved tikis, miniature statues, pearl crowns and the human bones of ancestors that they dare not anger.

A few summers ago, Jimmy tells me, four beautifully carved tiki heads were discovered during AFAR excavations. The archaeologists discussed the findings with the landowners, the Maieu brothers, and transferred the heads to the Maieu brothers’ home for safe keeping while it was decided what to do with the artefacts. However, that same night, when some of the archaeologists returned, the tiki heads had vanished. The Maieu brothers’ relatives had been adamant that, in order to avoid the curse of disturbing the heads’ mana, the tikis must be reburied in a secret place or taken out on a canoe and thrown overboard so that they might never be found again. They needed to remove any threat to their family. Gabriel’s brother Heehue was out on his canoe as they spoke.

The spiritual implications of my excavation work leave me a little uncomfortable. Regardless, many locals I speak to are enthusiastic about the benefits that the archaeological work have brought to the island. The Vaitahu museum, the only such museum in the Marquesas, stops their ancestral artefacts being shipped to Europe. Not all artefacts are viewed with nervous apprehension, they add. Ancient fish hooks are a particular source of pride because they connect modern Tahuatans, who still depend on fishing to live, to their ancestors.

Contemporary artisans have also been inspired by the archaeological findings. The French missionaries taught the people that they should be ashamed of their ancestry. They stripped them of their arts, their dress, banned their tattoos and their carvings and called their dancing heathen. A lack of written culture means that much of Marquesan tradition was lost to history. Now, because of the archaeological findings, carving is rife again in the island and many tikis are carved in the traditional styles that have been rediscovered.

Fati, the most popular tattoo artist in the island, has been gifted books and prints by various archaeologists and visitors working in Tahuata with details of traditional Marquesan tattooing. He now has a folder of traditional tattooing motifs and symbols – captioned with their meanings and well as full body illustrations of tattooed Marquesan peoples. Fati explains to me that these books and prints are invaluable to him, as they have introduced him to symbols, styles and patterns of ancient design that he had not seen before.

Before I leave, Fati gives me a traditional tattoo as a parting gift. Included in the design are waves – symbols of the future, what lies beyond the horizon; dolphins, a symbol of a strong bonds and eternal love; two small tikis – my future children, and a Marquesan cross, symbolising balance and harmony.

I lay down on the back of Fati’s truck and he pricks my arm with a needle for what seems like hours. His wife shells chestnuts on the floor with a machete; my anxiety about her fingers distracts me from the pain.

Words and Photography by Holly Fairgrieve; Produced by Antonio Perricone.