How Things Are Here

by Ng Wei Kai | July 20, 2019

Boon Hian shoots a hundred free throws before he allows himself to leave. It’s dark now, and everyone else is gone. Termites flit around above him, drawn by the smell of rain out and towards the floodlights. They come to mate and leave, but instead they fly in circles – banging against the plastic glow until, exhausted, they fall dying onto the court below. He does not notice. He feels only the filthy seams of the ball as it slips from his fingertips, hears only the heavy flick of the net and the single bounce it makes on the hard, orange asphalt before he retrieves it and returns again to the free throw line.

Back home he washes his jersey. Squatting on the bathroom floor he dips the faded polyester into a red plastic bucket, swirling it around in the soapy water before wringing it out. In the living room of their one bedroom flat the old woman watches TV. He hears the hum of the news, but cannot make out the words. Only a faint glow from the hallway, blue from the TV and red from the altar in the corner of the living room.

Suddenly, she is crying. On the television the Americans have landed on the moon. Eyes wide and streaming, she bats away his hands.

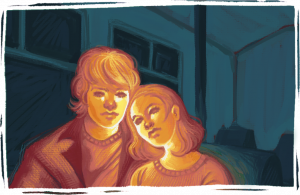

Boon Hian slips out into the corridor. Two floors down and three flats across, he knocks on a window. It opens, just a little. Dark eyes peer out; a careful smile.

Now they are sitting in a field. His legs are covered in mosquito bites, but he pushes the stings far away, absorbed. He slips his hand up to the edge of her jaw. The motion feels heavy, as if he is pulling through water. His mind is light with unfocused attention.

Anna’s gaze moves over his face. “You’re distracted again.”

He idly traces circles on her skin. “Do you think the universe has a consciousness? Do you think it knows about us?”

Anna presses her face to his thigh, gently grazing his skin with her teeth. Cars slide by in ones and twos. People – paired and unpaired – wander through dim yellow lights.

“Or do you think it’s more focused? I think it probably has its own kind of mind, not like ours. Like a tree maybe. Or a forest.”

“I don’t care.” She looks up at him. “When are you leaving?”

“She was screaming at the TV again today. The Americans landed on the moon. She thinks Chang’e is still up there with her rabbit. She thinks she’s still on a farm in China, she…”

He lets go of a tuft of grass he finds in his hand. Dirt falls from the roots.

Boon Hian gets up at five and walks to the bus stop. He gets on the first 154 and finds his favourite seat at the front of the upper deck. The windows are half open. He presses his face to the glass.

He’s the first one in the gym. It will be two hours before practice starts, but Boon Hian keeps shooting. One bounce, back to his spot.

The old woman wakes early. She pours rice into a metal bowl, rinses out the starchy dust and places it on the gas stove. It’s still dark, but the house is lit by a purple half-light.

She boils the rice into a congee, adding chicken, onions, and ginger to the thick liquid. This is Boon Hian’s favourite food. She heard him leave in the morning. He will be hungry when he’s home. He keeps playing even while the money dries up. Boon Hian is good at basketball. Anna from downstairs says maybe he can make money playing.

Anna says overseas anything is possible, and that people make money playing all kinds of things – music, basketball, other people. She does not know what Anna means by playing other people. More than this, she does not trust Anna. Anna, with her white husband. Anna, with her car, and her degree. She’s forgotten how things work. How things are here. Leaving is for rich people, for other people. Leaving is for good.

Maybe she should be happy for him – for them. She left as well, after all. Now everybody here is from somewhere else. Halfway through an onion, the old woman cuts herself. Warm red blood flows over the off-white chopping board. It trails down through the metal sink and out of sight. ∎

Words by Ng Wei Kai. Artwork by Kathleen Quaintance.