Queer love letters

by Rose Harris | June 3, 2024

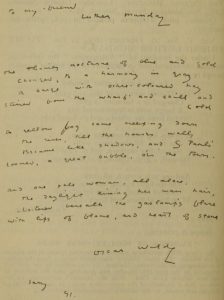

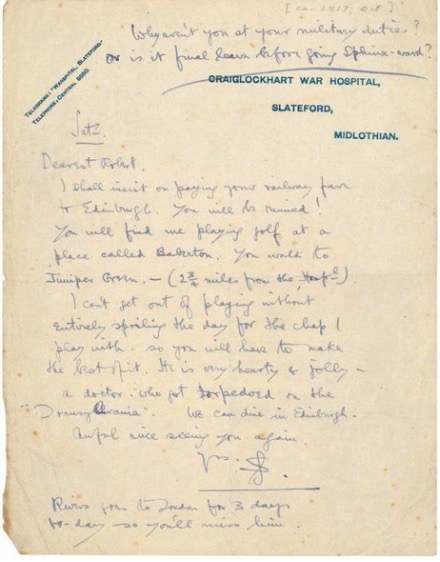

Letter from Wilfred Owen to Siegfried Sassoon. (University of Aberdeen)

In the enduring shadows of war, prejudice, and cultural turmoil, the resilience of queer love shines through. From the poignant letters of poets like Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, to the clandestine journey undertaken by Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. And across the Atlantic, where Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky openly embraced their love amidst the tumult of the Beat Generation, these stories interlace to illustrate the unyielding nature of queer love.

Their stories show us the unwavering determination and perseverance of queer love in the face of immense challenges. From the haunting echoes of World War I trenches to the covert struggles against societal prejudice and the bold defiance of countercultural revolutions, these narratives reveal the indomitable spirit of love that rises above barriers. Through the tender letters of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, hidden amongst the commotion of war, we can witness a love that defied societal norms and flourished amidst unimaginable peril. Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, navigating a repressive society, found solace in undercover affection, while Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky boldly proclaimed their love in an era of conformity and intolerance. These stories serve as reminders of the prevailing power of love, even in the darkest of times, and inspire us to embrace the diverse beauty of human connection in all its forms.

Owen and Sassoon, men deeply intertwined in a tale of passion and sacrifice, faced the daunting spectre of war. Their love blossomed in the trenches of World War I, where societal norms clashed with the harsh realities of conflict. The fear of discovery and constant threat of death forcing them to navigate love in the midst of unimaginable chaos and peril. Likewise, Woolf and Sackville-West embarked on a clandestine journey of their own, navigating the turbulent waters of early 20th-century Britain. As two women in a society rife with prejudice and discrimination, they faced immense challenges in openly expressing their love. Their relationship existed in the shadows, hidden from public scrutiny, yet their bond remained steadfast amidst the societal upheavals of their time. Then, amidst the cultural revolutions of the Beat Generation, Ginsberg and Orlovsky openly declared and embraced their love. However, their path was not without obstacles. In an era marked by conformity and conservatism, their relationship defied societal norms, inviting criticism and condemnation. Yet, their love endured, a beacon of spirit in a tumultuous age.

Through these couples and the challenges they faced – from the horrors of war to the constraints of societal expectations – we can admire and be proud of the strength of queer love. Despite the turbulent nature of their era, these couples forged bonds that transcended barriers, proving that love can survive even in the darkest of times.

In a time when queer love was resigned to secret corridors and the horrors of war shook the world, poets Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon found solace in a connection hidden from the world. Their relationship unfolded against the backdrop of the First World War, documented through poems and letters, serve as a poignant reminder of forbidden love.

Owen’s words to Sassoon echo with the resonance of an ardour that defied the constraints of their time. “In effect, it is this: that I love you, dispassionately, so much, so very much, dear Fellow.” Owen’s letter laid bare the depth of their affection. Their love, forged in the crucible of war, committed to letters read in the trenches. The pair met when Owen was sent for shellshock treatment at Craiglockhart Hospital in Edinburgh.

In early twentieth-century Britain, homosexuality was illegal under the under laws such as the Labouchere Amendment of 1885, which criminalized “gross indecency” between men; and was heavily stigmatised, considered both immoral and a mental disorder, with public and societal attitudes harshly condemning it. This made it essential for Owen and Sassoon to keep their relationship clandestine so as to avoid imprisonment, ostracism, and personal ruin. The pair would have also faced the additional struggle of a hyper-masculine culture in the military, which was deeply intolerant of anything perceived as unmanly, including same-sex relationships. Discovery could result in court-martial, dishonourable discharge, or even more severe penalties.

Yet, Owen’s admiration for Sassoon went beyond hero-worship. “You have fixed my Life—however short. You did not light me; I was always a mad comet; but you have fixed me,” Owen confessed. The intensity of their connection finds expression in Owen’s verse: “I spun round you like a satellite for a month, but I shall swing out soon, a dark star in the orbit where you will blaze.” The words become a dance of two souls entangled , a “dark star in the orbit” defying societal gravity.

Their love story took a tragic turn when Sassoon left the front lines and duty compelled Owen’s return to the battlefield. Owen succumbed to a dawn attack on 4th November, 1918, just a week before the war concluded and Sassoon’s grief echoed in his words, “[Owen]’s death was an unhealed wound. The ache has been with me ever since. I wanted him back—not his poems.” In the poetic communion of Owen and Sassoon, even the darkest corners of history couldn’t snuff out the flame of queer love .

Not long after, Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West had embarked on a clandestine journey that transcended the boundaries of ‘friendship’.

Though lesbianism would never be explicitly illegal, Woolf and Sackville-West navigated their relationship in an oppressive cultural milieu with intense social stigma surrounding same-sex relationships which meant that their connection had to be hidden from the public eye. Woolf’s ongoing battles with mental health issues and Sackville-West’s frequent travels only further tested their bond. The advent of World War II and its attendant fears and disruptions magnified Woolf’s anxieties about aging, failure, and her creative legacy. In this oppressive cultural milieu, their love persevered through poignant letters and rare meetings, serving as a testament to the might of queer romance against the backdrop of societal and personal adversities.

In 1922, Vita shared her enchantment in a letter to her husband, who was no stranger to homosexual affairs himself: “Darling, I have quite lost my heart.” Woolf, initially ambivalent, found herself drawn to Vita’s vitality and charm. Vita became not just a lover but a muse, inspiring Woolf’s revolutionary novel Orlando in 1928. Described by Vita’s son as “the longest and most charming love letter in literature,” the book immortalized Vita in the pages of Woolf’s prose. Separated by Vita’s travels, their letters echoed with longing. Vita’s heartfelt confession: “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia,” paints a portrait of deeply intimate reliance on her partner.

Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West at Monk’s House, in 1933. (Barbican Art Gallery)

Yet, Vita’s other relationships and the war’s onset dimmed their love and sent them on divergent paths. Vita, actively engaged, while Woolf grappled with the strains of war, the fear of aging, recurring bouts of insanity, and the dread of failure as a writer. This perfect storm strained the threads of their relationship. In 1941, Woolf’s suicide left Vita haunted, wondering if her presence could have altered destiny. Their love story, filled with coded messages and unspoken desire remains a tribute to the complexities of queer romance.

Beat Generation titans Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky acknowledged their love without reservation. Their bond blossomed amidst the mid-20th century’s cultural upheavals, and they found solace in the Beat movement’s authenticity.

Like our previous partnerships, Ginsburg and Orlovsky’s relationship developed in a society steeped in homophobia and conformity, meaning their open acknowledgement of queer love was an act of profound defiance. The cultural and legal climate of the 1950s and 1960s in the United States was largely intolerant of homosexuality, which remained criminalised in many states and socially stigmatised nationwide. They would face the constant threat of legal repercussions and the pervasive pressure to conform to heteronormative expectations which required them to navigate their relationship with a mixture of boldness and caution.

Ginsberg believed in embracing all of life. Their love became a sanctuary amid the espresso bars, spiritual quests, and artistic rebellion of 1950s New York. Journeys through Paris and Naples, encounters with literary giants, and adventures in the Bohemian Beat Hotel became chapters in their saga. Orlovsky, celebrating life’s pleasures, welcomed vulgarity in defiance of Puritan ethics, asserting, “the mind is used for enjoying the body.” In a letter from New York, he envisioned a world changed by their desire, “we’ll change the world yet to our desire—even if we have to die—but OH the world’s got 25 rainbows on my windowsill.”

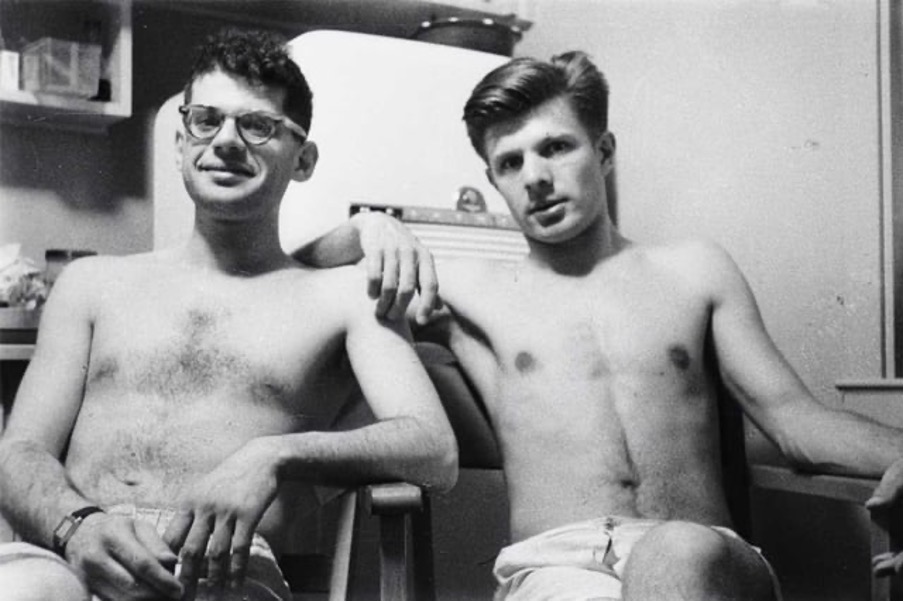

Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky in San Francisco, 1955. (University of Toronto Art Centre)

In their words, one can discern the echoes of a society’s discordant symphony, where the rhythm of love is often drowned out by the dissonance of societal expectations. Ginsberg’s heartfelt confession, “life seems emptier without you; the soul warmth isn’t around,” reverberates against the walls of societal constraint, a lamentation for a love constrained by the arbitrary boundaries of societal norms. Their letters, adorned with typos and quirks, serve as poignant reflections of the complexity that ensnares their affection, each misplaced stroke of the pen a testament to the tangled web of restrictions that seek to suffocate their love.

In the annals of countercultural history, the love story of Ginsberg and Orlovsky emerges as a defiant outcry against the incoherent restrictions that seek to stifle the natural flow of human connection. Etched into the fabric of time, their intertwined narrative becomes a rallying cry for love unfettered by the shackles of conformity, a testament to the strength of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

In a world where societal norms seek to mould love into a uniform shape, their love dared to be different, embracing the kaleidoscopic beauty of the human experience in all its glorious diversity. Each word penned, each sentiment expressed, becomes a declaration of their unwavering commitment to love in its purest, most authentic form—a love that refuses to be bound by the incoherent restrictions of a society in turmoil.

As we delve into these love stories, a truth emerges: queer love persists , resolute in the face of adversity. These tales remind us that love, in all its forms, is an eternal force shaping history and carving a lasting impression upon the soul.

Words by Rose Harris. Images courtesy of University of Aberdeen, Barbican Art Gallery, University of Toronto Art Centre.