Image of War: An interview with Don McCullin

by Jo Glanville | October 22, 2013

“I don’t like distance, I like to make what I do very personal and I like to get as close as I can in war so that I can show people the extreme misery of it and the futility of it – you might say I plunged my hand right into the blood”.

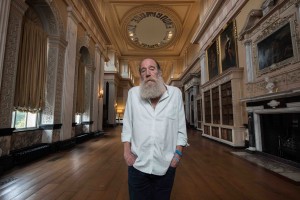

Don McCullin has been photographing the world’s major wars for the past eighteen years—from Vietnam to Beirut. He is widely considered to be the best war photographer in the world, not only for the quality and power of his pictures, but for his concern and involvement with his subjects.

He is a good-looking man, with a worn, sombre face. It is also a tough face and though he occasionally laughs, he rarely smiles.

He was born in London in 1935. When he was fifteen his father died—a victim of chronic asthma. “I began observing suffering long before I got to wars.” He had to relinquish the Trade Arts Scholarship he had won to go and wash dishes on a train. “I idolised my father for his courage. He never used to lie down, he always used to sit up and he never complained… I made up my mind that I was going to do something with my life. So I was very quick off the ground and I learnt very quickly how to become street-orientated.”

He is still deeply conscious of his tough working-class background. When his letter was published in The Times last summer, protesting against the War Office’s rejection of his application to go to the Falkland with the Press, he felt “very dignified” about getting his father’s name in The Times. “That’s the only name I’ve ever tried to honour.” He found out that his application was at first received enthusiastically. “Someone in higher authority turned it down. They said that I was the last person they were going to let go down there.”

So McCullin spent the summer in Beirut. “There is a breakdown in people now and I know it’s a terrible thing to say, but there is even a breakdown in the victims now, they are not behaving like they used to behave.

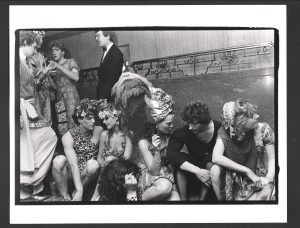

“Once upon a time covering war in a photojournalistic way with a very small 35mm camera was unique—now there are hoards of people doing it, there are battalions of newsmen now on jobs and what’s happened is that people look upon us now in a way as a very mercenary group.”

An experience he had in Beirut particularly disturbed him. A woman who had just lost her family attacked him in her grief and fury. She was shortly killed herself, by a car bomb. He felt ashamed and upset by the incident. “Years ago that would never have happened, because I waited for the consent of the atmosphere. I knew that if I brought my camera out I had the consent of the people, they used to say ‘Photograph this, show the world this’. But today with the new video cameras and the money that the American networks pour into the operations… they compete like mad to get the best news spots in America. They are spending millions of dollars each year, millions, to cover a tragic news story. There is a certain amount of obscenity in that.”

McCullin is clearly far from being a mercenary photographer. His colleague on The Sunday Times, Simon Winchester, spoke of him with admiration. “He leaves everyone else standing, he is very dedicated, totally dedicated… so many photographers are very detached.” McCullin can never cut himself off from the suffering he sees. He never carries a weapon and continually helps the victims. “You feel bad about photographing people who are down… by giving someone a sip of water, it’s not so much an act of charity, it’s an act of conscience.” In Vietnam he used to pick up soldiers and run away with them to safety then bandage their wounds. He himself has had many brushes with death and badly fractured his arm in El Salvador. He can still work, but he can no longer straighten it.

He relates his horrifying experiences in a dry, flat voice, sometimes acting them out. He describes in detail gasping mouths pouring rivers of blood, people bleeding from their ears and noses, people being stabbed and beaten. Almost like the Ancient Mariner, he is compelled to speak, haunted by what he has witnessed.

He is proud of his bravery and promotes a tough fearless image. He continually takes risks in battle, tempting fate: in Beirut he tested himself by going as near as he could to the cluster bombs which the Israelis were dropping. Yet he feels that women are braver than men and particularly admires the women who went to Greenham. “You will find that women have got a lot more guts in them, one of the reasons why they are so concerned is that they are the people who actually bring children into the world and so they’ve got a greater vested interest in their survival.”

With these contradictions in his character, one wonders what motivates him to keep returning to war. He admits that the risk involved is a challenge, he also wants to “Disturb people’s comfort or their ability to ignore.” He himself finds it difficult to explain. “I’m a terrible messed up person deep down inside, if I was calm and worked out I would never do it.”

He is now working on a book about Beirut, but his dream is to leave war photography altogether. “If someone gave me a bursary for the next ten years I would go and live in Scotland in a crofting house. I would stay there and photograph the landscape.” He is well aware how lucky he has been to survive so many wars, but is not quite ready to change his way of life. “What I really need is a really good crippling wound to the leg that would stop me walking.”