“The British will go down in history for being the absolute assholes of the world” – Lawrence Weiner

by Mayya Gulieva, Thea Bradbury | November 6, 2015

On the outskirts of Oxford, Blenheim Palace rises up out of the morning mist like it’s momentarily forgotten that the future doesn’t belong to it anymore. We’re here to meet Lawrence Weiner, the so-called father of conceptual art and creator of the second exhibition by the Blenheim Art Foundation (the first was of work by Ai Weiwei). His presence makes itself known even before we enter the building: blocky blue letters are suspended above the vast entrance, spelling out the words ‘WITHIN A REALM OF DISTANCE’. It’s the first of seven deceptively simple works installed throughout the palace, which are surprisingly fitting to their new surroundings. While ‘FAR ENOUGH AWAY AS TO COME READILY TO HAND’, a silver PVC banner that takes up a whole wall, seems like a mocking postmodern echo of the tapestries it’s hung alongside, the rich yellow of ‘NEAR & FAR & EQUAL MEASURE AT SOME POINT’, located at the western side of the Great Hall, gives it the appearance of an antique sundial. The words could be a biblical quotation exhorting patience.

What moved Weiner to take on the palace’s commission in the first place? He admits that he didn’t quite know how to react when he was first approached by Blenheim; “They said, ‘Would you be interested in the show?’ and I said, ‘I have no idea’. I was not looking for another show.” Weiner says that when he saw the space, “The thing that made me think it was a possibility was that it was not royal. It was regal, not royal.” In Weiner’s telling of it, the palace is closer to a museum or a gallery than to a royal castle: artworks and precious objects have accumulated here over time in the same way that a museum’s collection expands, and tell similar stories.

Nevertheless, Weiner’s personality seems strikingly at odds with the atmosphere and history of one of Britain’s most famous stately homes. Throughout our interview he frequently references his oppositional youth: “I am a product of the fifties, sixties and seventies, when the changes one wanted were complete changes. I got a tattoo that had a meaning that would get you busted in the fifties or sixties. But it doesn’t have the same meaning anymore; now it’s just a red star.” While his communist tattoo may no longer be so provocative, seventy-three year old Weiner remains a contrarian. He is contemptuous about the state of the art world, calling the British “the absolute assholes of the world” for daring to invent the PhD in Fine Art.

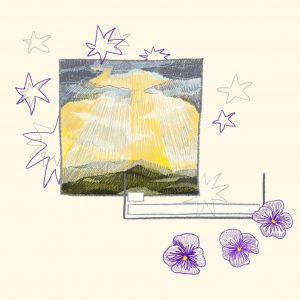

Perhaps Weiner’s own feelings on the palace are irrelevant, though, as the booklet accompanying the exhibition pointedly describes it as ‘a simultaneous reality / not a parallel reality’, and refers to Blenheim as a ‘support structure’ for the works, which should address the viewer’s relationship to the objects in their life. Whatever Weiner – or we – think of the location, then, is less important than the tools his artworks give us for relating to our own possessions. This concern to create something of use to the viewer is most evident in the seven blue-framed pieces of embroidery scattered throughout the exhibition. Much less intimidating than the works created to match the scale of the palace, these plaques bear statements such as ‘FOUND BY CHANCE AFTER ANY GIVEN TIME’ and seem to offer the viewer a set of instructions – though for what, typically, never quite becomes clear. Weiner provided the pieces and chose their locations, but it was up to palace staff which piece went where: “Anything you see is chosen by the people installing it. Not the location, but the content, and the content is really what counts.”

This do-it-yourself sentiment chimes with one of Weiner’s earliest works, his iconic 1969 Statement of Intent, which ran

- THE ARTIST MAY CONSTRUCT THE PIECE.

- THE PIECE MAY BE FABRICATED.

- THE PIECE NEED NOT BE BUILT.

Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist, the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.

It’s widely considered to be the gesture that launched the conceptual art movement, and gives Weiner’s work a certain universality, enabling any audience to recreate it using the materials and processes available to them. WITHIN A REALM OF DISTANCE, then, is less an exhibition than a provocation; a contrarian nod to Blenheim’s history that challenges its viewers to shape a new narrative from the objects surrounding them. “The point of the whole operation,” says Weiner, “is to change the logic structure within the configuration that you are not happy with. But you make art because you are not happy with the configuration of the way people relate to… a cup of coffee? So you attempt to build something that changes that relationship.”

This might explain why Weiner is hostile to the teaching of art: after all, you can’t teach a student how to change the world. That’s something that everyone has to figure out for themselves. Similarly, when we ask him what his key advice for a young artist would be, he simply responds, “Make art.” He does, however, concede that you can teach an art student particular skills to help them on their way. “Teach what the world knows at the moment – maths, physics, drawing, etc – not what somebody, a tutor, thinks. Just teach what exists and let somebody build from that: reject it, accept it, use it.”

Weiner is clearly not a man to give easy answers, and WITHIN A REALM OF DISTANCE bears a distinct resemblance to its creator. Pre-interview, I’d strained my neck staring up at an installation on the ceiling of the Long Library. It proclaimed, in black, silver and gold capitals, ‘MORE SALTPETER THAN BLACK POWDER / ENOUGH BLACK POWDER TO MAKE IT EXPLODE’. A reminder of Blenheim’s past as a reward to the Duke of Marlborough for victory over the French? A reference to Weiner’s own early work with explosives? It’s up to me to decide, and then, at least according to Weiner’s utopian imaginings, it’s up to me to do something useful with that decision. WITHIN A REALM OF DISTANCE does not offer meaning: it offers potential.