Nollywood

by Alex Dudok de Wit | January 24, 2013

When the American Mafia, unhappy with the way it was being portrayed in the film, tried to shut down the production of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, the affair became Hollywood legend. In Nollywood, gangster intervention is standard. Local thugs turn up at the makeshift film sets that dot the streets of Lagos, and extort money for ‘protection’ that they don’t provide. Violence is rare, but the director has other problems to think about: traffic jams hold up the crew for hours at a stretch, overworked actors arrive late from other sets, and generators turn off without warning, plunging the cast and crew into darkness. Franco Sacchi’s documentary This Is Nollywood has a scene in which filming on a set is interrupted when a nearby mosque starts booming prayers out of a loudspeaker. In Lagos, the chaotic nerve centre of the second-largest film industry in the world, it’s a miracle that films get made at all.

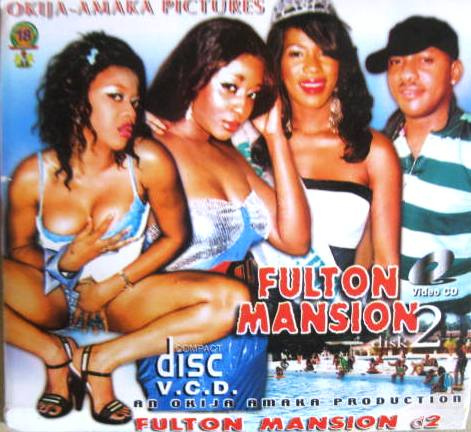

Until 1992, they didn’t. Before the advent of cheap digital cameras, films were too expensive to make; and before the wide dissemination of videocassettes, few had the means to watch them anyway. But in that watershed year, Nollywood was born by accident when Nigerian trader Kenneth Nnebue found a novel way to shift thousands of blank cassettes that he had bought from Taiwan. Deciding that they would sell better with something on them, he hurriedly wrote and shot a film called Living In Bondage about a man who is encouraged by a sinister cult to kill his wife in return for riches (the title refers to spiritual bondage). The film promptly sold 750,000 copies and spawned legions of imitations, each one as cheaply and quickly produced as Nnebue’s original.

The rest is not quite yet history – Nigeria’s film industry is still in its nascency, and few of the films to come out of it have risen above the standards set in 1992. Yet in less than two decades, Nollywood – the world’s first all-digital film industry – has already surpassed every other national cinema bar India’s in the quantity of its output. In Jamie Meltzer’s film Welcome to Nollywood, we meet Nigerian filmmaker Chico ‘Mr Prolific’ Ejiro, who is so committed to efficiency that he edits scripts before reading them. Ejiro wears his nickname like a badge of honour, printing it in bold on all of his films’ posters: Nollywood values speed above all. “This is an industry that exists because of the democratising effects of technology”, Meltzer tells me. “It grew out of very specific conditions, which the artists, filmmakers and entrepreneurs took advantage of.” This means that filmmaking in Nigeria is a medium for the masses and not the elite – an important distinction n a country whose recent history is coloured by oppressive imperial government.

Up to two thousands films are made every year. A typical production lasts for fifteen days, and costs around $15,000. On average, fifty thousand videos and DVDs of the film (in a country with only eight cinemas, the industry necessarily centres on home media) are then sold for a dollar or two apiece. Bandits have caught on: cheap pirate copies of a film start to circulate two weeks after its official release, and so this fortnight is known as the ‘mating season’ – the period in which the distributors must make their money before they lose control of their product. Thus piracy drives Nollywood’s ‘cheap production, quick turnover’ mentality.

Sacchi believes that the industry is motivated entirely by financial profit. “In my documentary, the Nigerian director Mahmood Ali Balogun says that ‘Filmmaking in Nigeria is a kind of substance filmmaking… if you don’t make the next film, you are not going to feed.” Fittingly for a cinema that was born of a trader’s cynical business move, financial gain and the culture of glamour are big attractions. Superstar Nosa Obaseki. Sums up the spirit when he says, “I am like a king… people worship me. I never pay for taxis or restaurants.” An archetypal plot focuses on an individual’s pursuit of wealth, and many films give an upbeat depiction of the good life, complete with suits and champagne (although the budget never allows for a real bottle to be used).

Directors and screenwriters, far from tapping into their own creative instincts, instead supply whatever kind of film the public demands. Coupled with the industry’s fluid production model, this makes for a fast-changing scene: Meltzer describes to me how, within eighteen years, Nollywood’s passed from a period of films about ‘occult activity’, through an ‘epic’ phase of ‘period films about West African history’, to romantic and action film fads. But Sacchi believes that overriding all this is the Nigerian people’s insatiable appetite for home-grown narratives. “Watching their own African stories provides a psychological relief. A woman told me that after a stressful day in Lagos she could almost breathe better while watching a Nollywood move. ”Stories of lost tribes, collapsing empires, revolting slaves – crucially, they are stories that everyone in the country can relate to.

There’s no time for quality control. I spent six hours watching Nollywood films on Youtube (search ‘nollywood movies’ and enjoy), and came away as unsatisfied as if I’d spent the whole afternoon in a tepid bath. The special effects would look bad in a Super Nintendo game, and hammy acting and stereotyped characters are the order of the day. Soundtracks rarely consist of more than a ten-second theme looped endlessly throughout the film. The plots are a black-and-white affair: wealth is good, murderers and adulterers are punished, baddies practise juju witchcraft, goodies are God-fearing Christians. The highlight of my marathon was a scene in which the protagonist prays to God for an iPod, and duly receives one in the post. Indeed, despite the fact that one in two Nigerians is Muslim, Nollywood films are suffused with Christian values and imagery. Many pivotal scenes are set in churches, Jesus is often dispatched to bring on a character’s salvation at the end of a film, and closing credits are followed by the invocation ‘To God Be The Glory’. Christianity is on the rise not just in Nigeria but in all of Africa, and so the films’ plots and morals resonate with viewers across the continent. In addition, Nollywood films export easily because they’re generally made in English, the nearest thing to a common African language. It’s perhaps ironic that a film industry so emphatically nativist, so determinedly anti-elitist, owes much of its success to two relics of the colonial age: Christianity and the English language.

And such is the success of Nollywood films across Africa that some accuse Nigeria of launching a sort of cultural imperialism of its own. Kids in the Gambia speak in accents learned from the films, while politicians – such as the president of Sierra Leone – generate publicity by inviting Nollywood stars to accompany them on their campaign tours. African governments feel threatened. Ghana (which now has a thriving cinema of its own – ‘Ghallywood’?) imposes a tax on visiting Nollwyood filmmakers and actors, while the Democratic Republic of the Congo has outright banned the broadcasting of Nigerian films on television. Ernest Obi, head of the Lagos actors’ guild, takes a different point of view: “We give Africa development and knowledge. If they call us colonial masters, too bad.”

Whether this ‘development’ and knowledge is transmitted through the films themselves or through Nollywood’s outrageously efficient business model is unclear. Sacchi is of the opinion the whole world would benefit from studying the economics of the industry, even suggesting that its model “could be replicated in other areas such as energy and manufacturing.” Meltzer also recognises the importance of Nollywood films’ thematic content. He tells me that they are inciting other African nations to make films “by, for, and about themselves; a real antidote to the monoculture that often results from the disproportionate impact of Hollywood.”

But outside of the diaspora market, Nollywood hasn’t found a mainstream audience in the West (Nollywood did not feature in Oxford’s 2010 African Film Festival). This may be because their storeis are not as effective in countries that have already attained wealth and democracy, or that are not versed in Nigeria’s history and folklore. It may be because the films are, by and large, crap. There have been crossovers – Jeta Amata’s recent Black Gold, featuring Billy Zane and Tom Sizemore, is a well-known example – and as budgets expand and quality takes precedence over quantity, there is potential for many more. But Sacchi is quick to dismiss this goal: “What is important is that Nollywood sustains job growth in Africa. Hollywood can wait.”

Image by Nollywood Forever