From Africa to the Amazon

by Mark De Courcy Ling | March 19, 2019

In an indigenous community in Northern Brazil, I sat with a group of community leaders in a wooden-clad room. I was taking part in a project with Vaga Lume (‘firefly’ in Portuguese), an NGO that works to improve education in roughly a hundred communities in the Brazilian Amazon. In the community meeting room, a fan mounted in the corner was whirring gently, stirring up the heavy air. The lime-green paint on the walls had flaked over time due to the perpetual heat and humidity. It was November, and summer temperatures were beginning to take effect. Fanning themselves with sheets of paper, these community members discussed the politics of Brazil. Just a week before had seen the election of a new president in Brasilia, the country’s capital, nearly a thousand miles away from their home. President Bolsonaro, at the time the president-elect, left no ambiguities in his campaign that the protection of the rainforest, and the rights of the indigenous communities within it, were nothing but a barrier to Brazil’s economic rise: “where there is indigenous land, there is wealth underneath it.” I sat there listening as they talked of what would happen to the land and environment on which their lives depend. It seemed inconceivable that events in Brazil’s southeast, the most urban and industrialised region, could filter through into the lives of people like these; inhabitants of riverside communities scattered throughout the Brazilian Amazon.

The Amazon is a place where cultures and narratives are created and destroyed in equal proportion. It is a place that’s been morphed, manipulated and made home by people from almost everywhere in the world. As such, it forms part of the puzzle of our own past, the construction of our nation, the formation of the world as it is today. Yet over hundreds of years, little about the way we view the people of the Amazon has changed. A palatable image is generated by Western media to encapsulate them, reducing them to a trope: naked tribesmen, hidden behind green foliage, armed with spears and blow pipes, gazing curiously at the sight of westerners. Above all, these people are regarded as distant, isolated, and “primitive.” It is an image that lingers as a romanticised remnant of the period of European colonisation, a fetishised presentation of ‘New World’ cultures as objects of intrigue, coffee-table ornaments, cabinet-fillers in the British Museum.

Many members of this village, the community of Atodi in the North Brazilian state of Pará, are indeed ancestors of indigenous people as Western media understand them. Some carry their babies on their backs in bags made of cloth. Some even continue to speak languages such as Tupi that existed before the introduction of Portuguese.. So the question remains: what lies behind this romanticised narrative? What about the people who can be contacted? And what is it about them that makes their story so much harder to find? To untangle the mystery of the Amazon and challenge the misconceptions surrounding it, we must look into the lives of the people who live there.

Between wildlife documentaries and televised ‘explorations,’ a typical Western narrative is that the Amazon is, and always has been, a hostile environment for humans. Often romanticised as an ‘untouched mystery,’ it is implied that whatever human life exists there must be so sparse, so brutal, that it is has not been touched by the reaches of meaningful global expansion. However, evidence found in the last decade reveals that the Amazon has a long history of human settlement. In contrast to famous, relatively intact Amerindian settlements like Machu Picchu, pre-16th Century Amazonian communities lacked long-lasting building materials like stone, so the remnants of their societies have been difficult to trace. However, the complexity of these settlements is now coming to light. Thanks to thousands of years of experimentation, Amazonians developed sustainable farming techniques that both suited their needs and maintained the biodiversity of the forest. The cause for their decline, more so than the genocides committed by Spanish and Portuguese colonisers, was the introduction of European diseases such as smallpox, typhus and influenza, against which the native populations had neither immunity nor protection. Immediately prior to European contact in the early 1490s, North and South America are likely to have supported between 90 and 112 million people, a figure greater than the estimated population of Europe in the same period. In the first hundred years of European exploration of the Americas, the indigenous populations were divested: reduced by 90%.

And so the societies of the Amazon Basin were almost wiped out, and with them went their art, music, creativity, farming systems and societal structures, along with everything else that constituted their existence. In essence, a significant piece of human history has been lost and Western society is only now beginning to realise this.

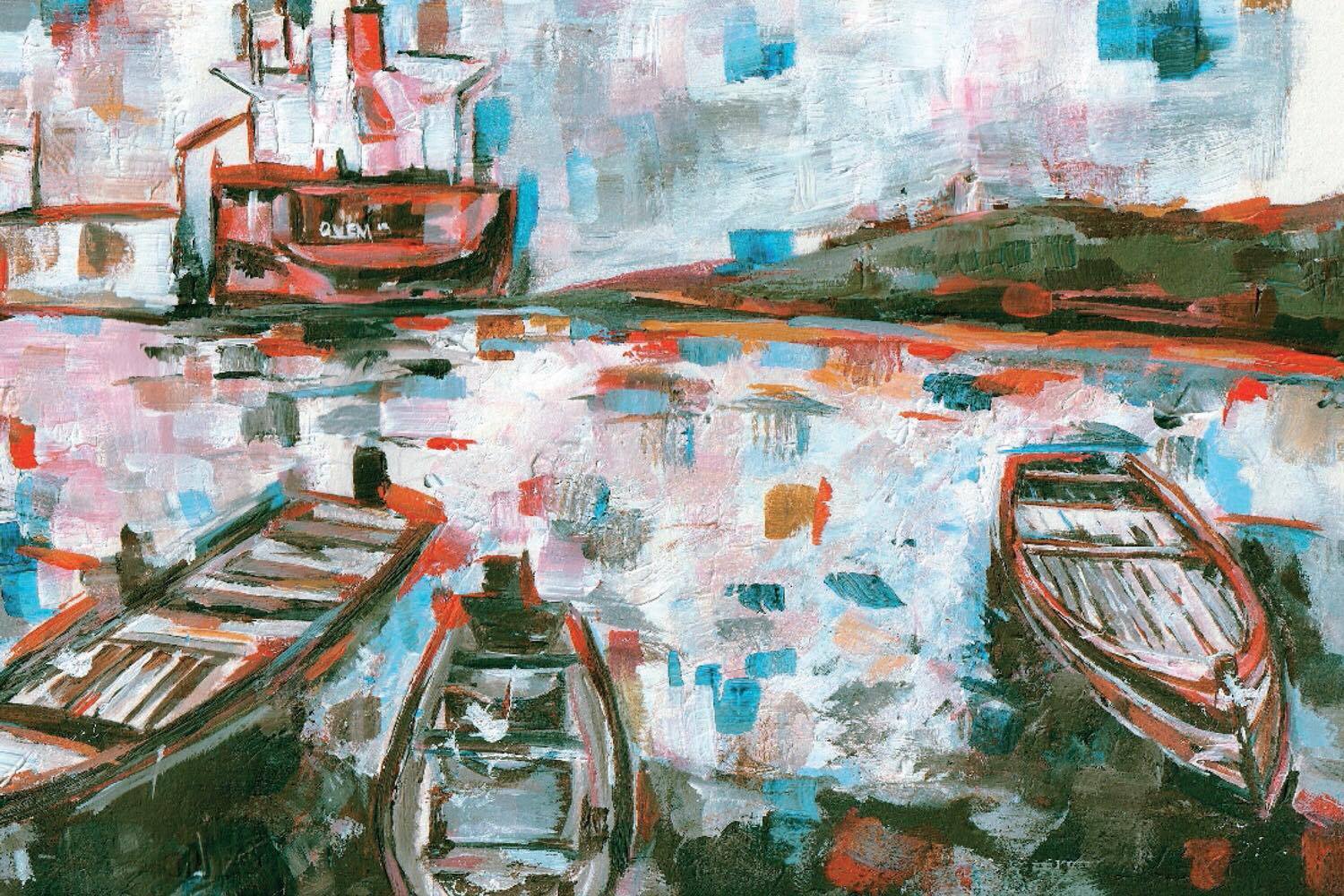

Today, huge cargo ships, sent by American and Chinese companies, slug their way up and down the Amazon’s main waterways. They contribute substantially to the economy of the entire Amazon region, transporting minerals and other raw materials to far corners of the world. Yet their engines pollute the rivers in which local communities fish. A complacent fisherman, having moored up in a place exposed to the awesome wake of an international trade ship, can have his boat capsized by the wave as it meets the shore. Near the town of Oriximiná, one village has given up fishing altogether; propped up on stilts to protect against the fluctuations of the river, its houses have almost all been converted to brothels. Like many towns near major ports, the village attracts passing trade from the sailors of these cargo ships. The money at stake from this is simply too much to refuse.

Priscila Fonseca, coordinator of the Network Program at Vaga Lume, a woman who has dedicated much of her adult life to the communities of the Amazon, describes the situation today: “there is a lot of international influence in the deforestation and in the huge plantations and cattle ranches in the Amazon. It is a huge shame because they are losing their own land, losing the forest and losing their quality of life. This is not something new. It is the accumulation of many years of exploitation of the land and the local people.”

Government involvement in the Amazon has, historically, been questionable to say the least. By and large, the relationship between politicians in Brasilia and the people of the Amazon is characterised by neglect. Lack of investment in public services, principally in education, has left the Amazon with a Human Development Index score drastically behind the rest of Brazil. The head teacher in the community of Atodi understands the importance of an educated population: “It is essential not to let these children be imprisoned by their lack of knowledge, because this is what makes our population a passive population, a population that does not understand the complexity of the world.” In other instances in history, the government has been more instrumental in pushing these communities even further behind. The military dictatorship in the 1960s, ’70s and ‘80s, having discovered gold in Roraima, a small state bordering Venezuela, encouraged the influx of Brazilians from outside the Amazon to expand mining production there. The white population more than doubled in two decades. With the newcomers came new diseases to which the local population, again, had neither protection nor immunity. In a virtually unthinkable feat of government neglect, thousands died from illness and malnutrition. Evidently the lesson of foreign disease introduction from the 16th century had not been learned.

Alongside the history of indigenous people runs a more hidden story. The Afro-Brazilian inhabitants of this village, the community of Atodi, represent a crucial yet little-publicised fibre of the Amazon narrative. They are descended from some of the millions of Africans brought over the course of a few centuries to this wet, equatorial habitat, thousands of miles away from their home. In this way, they and their predecessors have become part of the Amazon tapestry. Slavery has proved to be one of the most defining aspects of Brazil’s ethnic make-up, and the Amazon is no exception. It is for this reason that woven into the anthropology of Amazonian communities is a complex African heritage. Rubber plantations owned and run by Dutch and Portuguese ‘rubber barons’ imported enslaved West Africans to do the legwork. They were forced to sap rubber from the trees in the heat and thick, punishing humidity of the rainforest. Locals jokingly describe the weather in the Amazon as having two states: “inverno e inferno” (winter and hell.) For the Angolans arriving on slave ships in Northern Brazil, “inferno” alone would have been more fitting.

Due to favourable ocean currents and a relatively short shipping distance from the outposts of West Africa to the ports of Brazil, African slaves were sold cheapest to the Brazilian market. The scars of slavery are felt as acutely in Brazil as anywhere in the world. During the era of the Atlantic Slave Trade, an estimated four to five million African slaves were sold in the then-Portuguese colony. The United States and Canada, by comparison, imported 400,000. Since the cost of replacing a weakening slave was lower than the cost of adequately feeding one, the quality of life for the slaves that worked the mines, sugar cane fields, coffee and rubber plantations across the country was particularly low. The life expectancy of a slave in Brazil was substantially lower than the equivalent in the United States, where the lives of the comparatively expensive slaves were priced high enough to merit a plantation owner’s longer-term investment.

The climate was not the only cause behind the degradation of these slaves. Regardless of their respective linguistic and cultural differences, these people were shipped, housed and sold together. The Atlantic slave trade activity in Brazil was the first of its kind that made active efforts to wipe out the identity of the slaves. Once delivered to their destination, they ceased to be classified by origin or name; they were now simply ‘slaves.’ Since oral traditions were the primary method of passing down cultural identity, without effective communication, there were few ways to retain them. The result was that the traditions and stories told from one community member to the next became extinct, and with them went the identity of the enslaved.

Many Afro-Brazilians today have never been taught about the injustices suffered by their ancestors, an indication of the deficits in the Brazilian education system, and a gap in the consciousness of the country’s past. “When I was a child there was no reference to the process by which black people arrived in Brazil,” Priscila tells me. She describes her experiences growing up there: “textbooks at school had two or three pages on slavery, but I didn’t know who these people were before being enslaved here. I never had black teachers, or saw black people on television or in magazines. It had a major effect on my self-esteem, and it hindered the process of getting to know myself as a black woman.” Conceição Evaristo, one of Brazil’s most prominent Afro-Brazilian female writers, is a telling example of this underrepresentation. A woman who grew up in a family with nine other siblings in a favela in Belo Horizonte, she was until recently, ironically, more well-known outside of Brazil than within.

For the slaves sent to the Amazon in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, this hellish life was often too much to bear. Suicide attempts, a transgression that carried its own penalties, were a common occurrence. For others, perhaps the younger, stronger Africans on the plantations, escape seemed a better option. They fled by whatever means available, be that paddling makeshift canoes up hundreds of miles of river, or simply running into the murky, impenetrable forest. Some slave owners, such as the Dutchman, Friedrich won Weech, saw the first escape attempt as part of the breaking-in process of a new slave. Most escapees were unsuccessful; with hardly any knowledge of what continent they were on, let alone the geographical features of the surrounding equatorial landscape, they were quickly caught. As punishment, they were forced to wear an iron collar around their neck for the remainder of their life, which, as one can imagine, was not very long.

Some escapees, however, evaded the hands of the plantation owners. Learning from the indigenous communities already present in the Amazon, they harnessed its natural abundance in a miraculous bid for survival. By living in small groups that gradually transitioned into settlements, villages and communities, they used their rapidly developing knowledge of the dense jungle as protection from their captors. These communities of escaped slaves became known as quilombos. During the era of slave trafficking, natives in central Angola, called Imbangala, had created an institution called a kilombo that united various tribes into a community designed for military resistance. It is widely accepted that the term quilombo derives from these communities in West Africa. These quilombos, inhabited by quilombolos, have a culture of community spirit and fighting. Due to the historical subjugation of these people, to this day foreign white Europeans are often treated with extreme suspicion. When the NGO team in which I was working tried to access one particular community, being a white gringo, I was not allowed to enter. Their political attitudes are characterised by an attitude of resistance. Collective ownership and shared responsibility are paramount values and have been historically vital to the survival of such villages since times when slave-owners actively hunted for them. Priscila summarises her experiences of such a culture of resistance: “it is something very powerful to see that, even after five hundred years, the people of these communities are still looking after the land, respecting each other, and fighting for the right to what is theirs: their land, their communities and their traditions.”

The natural setting of the Amazon also has an important part to play in the survival of its inhabitants. The abundance of water, heat and sunlight creates an intensely fertile and hospitable environment for life. The importance of caring for these surroundings is something ingrained in the consciousness of these people. The forest, a plentiful resource on which the communities depend, is treated with a level of almost mystical respect and appreciation. Whether during the summer or winter, no one enters it between 6 o’clock in the evening and sunrise the following day. There are a variety of stories and legends that uphold rules such as these. From 6 o’clock onwards, the forest is said to be teaming with demons. One of them is a young boy with long red hair named Curupira. He resembles a normal human child in all senses other than his feet, which face the wrong way round. In this way, he runs around the forest leaving footprints that create the impression he is running in one direction, when in fact he is running in the other. Hunters, mistaking his trail for a boar or other small game, follow his footsteps into the wilderness, and they subsequently never find their way out. Two of the community leaders in the meeting in Atodi explained to me the significance of stories like these: “It’s very important to us to believe in something in which our parents and grandparents believed.”

“It’s not a myth.”

“No, it’s not a myth. It’s a truth, because we believe in it.”

It is these stories that revive the oral traditions that were lost in the process of displacement. In this way, the community members have cultivated a vibrant culture of their own. The will to sustain life, to sustain culture and identity, has survived the test of hundreds of years of oppression and thousands of miles of displacement. And so, they too have created a home in the Amazon, tapping into the lifelines created for them by the river and the natural abundance of food. In this way, they shape their own history and their own narrative. It is an inspiring story of human resilience.

Meanwhile, the unbridled process of international excavation of the Amazon’s natural resources continues to accelerate. The recent election and inauguration of Bolsonaro, a politician whose policies are more hostile to the Amazon than any other presidential candidate, serves as the most recent escalation to a set of problems centuries old. As such, community resilience alone is unlikely to prevent the disintegration of the Amazon’s diverse array of human life. Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian communities are running an ever-greater risk of their lands being taken from them. Priscila concludes: “I feel sorry for the risk not only to traditional peoples but to all Brazilians and to people all over the world, because if we devastate the Amazon it will impact all of us, not only through climatic changes, but also through the destruction of our human heritage”.