Paper Paraphernalia: What we can learn about Oxford from the way we use noticeboards

by Oliver Grant | November 15, 2023

While the listed sandstone persists, the student communities that animate Oxford’s city centre come and go with what — when compared with the lifespans of the buildings they’re surrounded by — seems like a dizzying speed. As students, we come to Oxford with the intention of being shaped by our experience in the city, but we also shape the city while we’re here. The physical footprint we leave behind is primarily a paper one — the countless essays, problem sheets, and admin documents we each produce form one important part of this, but another equally important part consists of the contributions we make to the city’s copious collection of noticeboards.

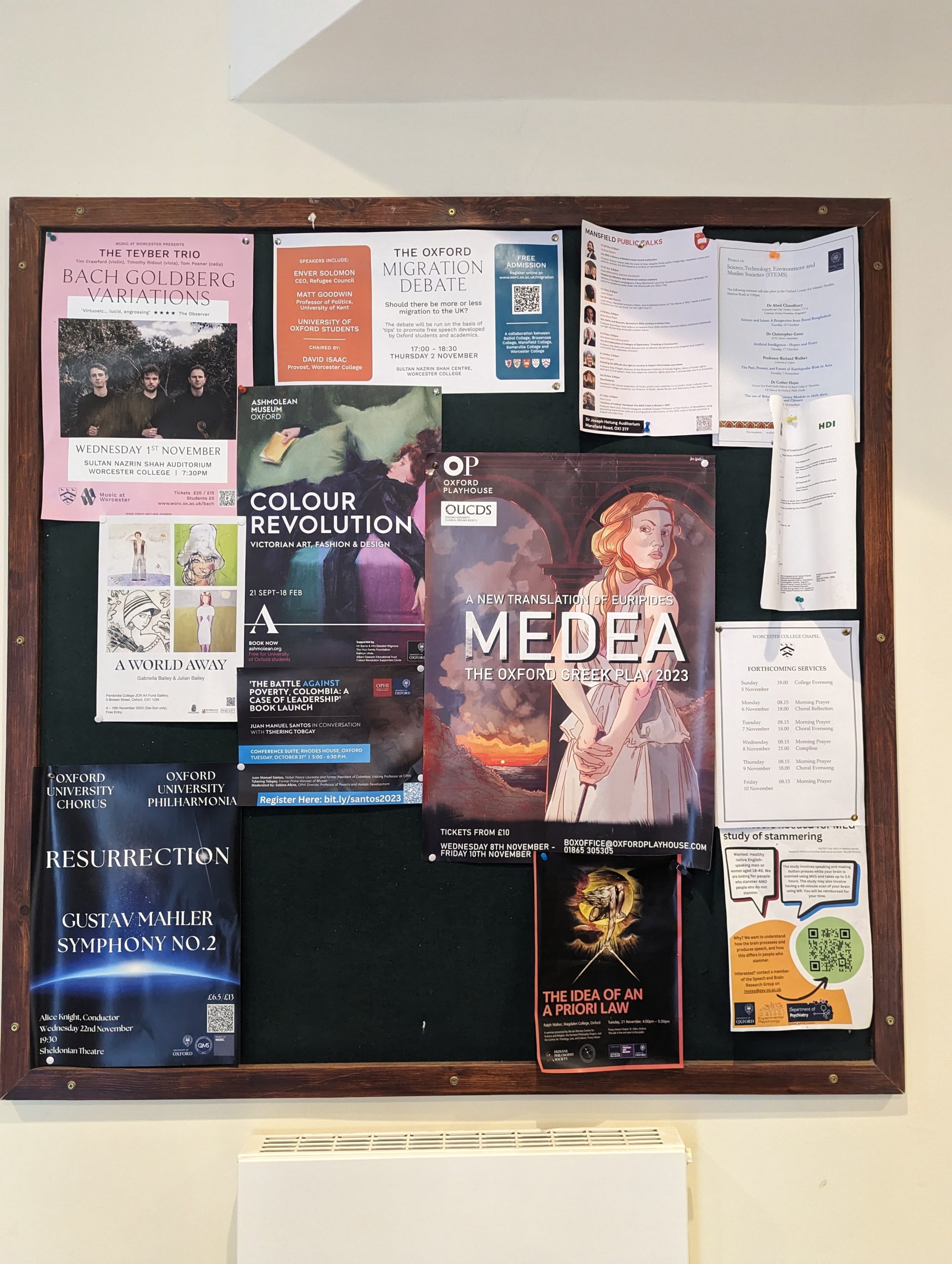

When you walk into virtually any university-associated building in Oxford, one of the first things you’ll see is a (usually cork) noticeboard. Throughout the city, cafés have their walls plastered with posters, and the familiar signs (mostly advertising classical concerts) huddle together along Holywell and Broad Street. Oxford is awash with paper advertising, and in many ways the constant pinning up and tearing down of promotional materials constitutes the city’s heartbeat. Unlike the colleges we belong to, which, although we live in, no more belong to us than to the tourists who come to visit — they’re just as capable of appreciating and admiring the buildings as we are — the posters which populate the city are uniquely ours. They reflect the activity of Oxford’s inhabitants, and they require local knowledge to be interpreted and understood. They’re the physical manifestation of the aspect of the city’s life which can’t be gleaned from a mere glance.

As students in a collegiate university, the hierarchy of noticeboards we encounter reflects the structural organisation of our academic lives. Every undergraduate room comes with its own cork board — the part of wall designated to tolerate students’ attempts at making their rooms feel like their own. Then you have the staircase or building noticeboard: a forum which carves out a community from a group of people who share a front door. These are often home to necessities like contact details of welfare staff and folders of JCR-funded ‘staircase condoms.’ Then the college noticeboard, drawing wider audiences still. And finally, the city-wide noticeboard. One particularly interesting phenomenon occurs when posters migrate from their original homes to somewhere higher or lower on the hierarchy. A poorly torn-down ‘Marxism in 20 Minutes’ advert stuck up in an undergraduate room or an endearingly hand-designed notice pinned up in an incongruously public setting are unexpected and amusing examples of the public and private intruding on one another’s territory, highlighting the role that noticeboards play as an interface between our public and private lives.

Noticeboards offer a snapshot of constantly evolving student communities and priorities. Recently there’s been a lot of orange, as Just Stop Oil seize the zeitgeist, and it seems likely that if the situation in Gaza continues we might start to see more and more black, white, green, and red too. The noticeboard, however, is a varied forum, and alongside these serious calls to action you will inevitably find a gaudy advert for an upcoming Bach performance and the work of an (often overzealous) OUDS marketing director.

Although largely impermeable to tourists, the fundamental charm of noticeboards and other forms of poster proliferation is their immediate and universal accessibility. You don’t have to be in the right circles, or part of a certain Facebook group, or following a particular Instagram page to notice a flyer pinned to a felt board. A culture of DIY paper advertising is one in which communities are uninhibitedly open and one in which people can discover events, causes, groups, and other people without any prerequisite social network. This is powerful tool, especially in a city which has so many inhabitants who are merely stopping by for a few short years before moving on. The transient nature of student life necessitates this symbiotic relationship between newcomers and communities: people rely on communities to be easily accessible so that they can participate in the city’s life during the short period of time for which they’re here, and communities in turn are forced to eagerly recruit in an effort of self-preservation. Paper advertising provide a key avenue for the realisation of this cyclical process.

There is of course, however, a qualification to be made here. We might wonder exactly how universally accessible those noticeboards tucked away in pidge rooms and Porters’ Lodges or hidden behind Bod-card-guarded doors really are. And somehow the issue seems even worse when student-oriented posters dominate in more public fora. It is clear who our noticeboard culture is for, and it is similarly clear who it is meant to exclude. Perhaps it is unsurprising that our poster culture reflects the city centre’s general hostility to Oxford’s permanent residents, yet it is still striking to see such a clear visual analogue of the squeezing out of Oxford’s townspeople.

But the situation is not all doom and gloom. New Marston provides us with a shining example of a truly residential noticeboard. Located on the corner of Ferry Road where it intersects with the Marston cycle path, the New Marston South Residents Association Noticeboard is a standalone structure with the sole purpose of bringing people together and informing the local community. The events advertised seem rather quaint — lots of Church fêtes and knitting groups — and notices are often left up long after the dates printed on them, but this charmingly reflects the relaxed pace and banal joys of suburban life. While the city centre becomes ever increasingly student-populated and student-oriented, residential communities continue to engage in the creation of DIY physical advertising.

The short cycle from hot-off-the-press technicolour sheets freshly tacked, pinned, stuck, and plastered onto Oxonian walls to wayward flyers turning to mulch amidst a pile of soggy autumn leaves more than resembles the blazing brevity of the time that we spend here — it embodies and records the communities and people that breathe life into Oxford for a few years at a time. So next time you’re walking into Magdalen Street Tesco or passing by your Porters’ Lodge, stop and admire the handiwork of your fellow students — it won’t be there for long.∎

Words and photography by Oliver Grant.