A Summer Sliced Up: my two months in a Singaporean kitchen

by Joy Wang | October 21, 2018

Saveur is an affordable French restaurant nestled between swish corporate offices and a busy shopping district. It has travelled a long way from its humble beginnings as a modest stall in the far-most corner of a large food court, the passion project of two young Singaporean chefs who sacked off their office nine-to-fives to bring affordable French food to Singapore. Three hundred restaurants open and close every year in central Singapore, yet the fame of Saveur’s dishes has weathered it through eight years of market instability. You only need to glance at the menu to be drawn in: their signature duck confit and sweet rolled angel hair, a crispy pork belly and cassoulet—and, most famous of all, their legendary pistachio panna cotta. The restaurant’s location and decor is far from fancy—all polished plastic tables and white tiled walls—but their food attracts a faithful audience of Singaporean yuppies, who eat and drink to the sound of Ed Sheeran’s ‘Shape of You’.

The first thing I notice when I arrive in the kitchen—working a summer job—is that all the chefs around me are young Malaysian and Mandarin-speaking men. They sneak surreptitious glances at me as I cube the carrots and shelve the dishes. I am the new girl, the small Singaporean hiding her deficiency in Chinese by communicating exclusively in smiles and nods. Han, the front chef, stands next to me stirring the soup. He attempts to speak to me in broken English but I struggle to hear: the kitchen is loud and lively, everyone’s laughing and cracking jokes. During dinner service frenzied people continue to ask me questions in Chinese that I have to ask them to repeat once, twice; more than three times.

I am the exception in the kitchen, that much is obvious. Singaporeans like me tend to shy away from this kind of low-pay, labour-intensive, long-hour employment—leaving Malaysians to pick up the slack. They dislike the job as much as Singaporeans, but when you have committed three years of intense study to culinary school, there is no option but to take what you’re given. Everyone in the kitchen dreams of success. While pouring out the soup, Han tells me of his dream to set up his own nasi lemak (spicy coconut rice) restaurant. Progress is slow—hindered by sky-high rents, amongst other things—but his dream persists: “I’ve nailed the chilli sauce”, he tells me, “so now I just need to nail the rice.” All the chefs dream of owning their own restaurant in Singapore, though few will likely succeed.

A typical day’s work goes like this. I arrive at the kitchen at 10.30am, wearing cargo pants and clunky waterproof shoes, before I swap my shirt for a chef jacket and head into the kitchen, murmuring a shy Mandarin “good morning” to Eric and Thomas, who are already boiling potatoes and roasting the pork in preparation for lunch. Eric looks about my age, carries his shoulders in a boyish hunch and wears a flashy pair of sneakers, while Thomas is plump, bespectacled and slightly nerdy. I join them, heaving out two big pots in order to make a start on the mushroom soup and begin to wash and dry the salad in a large spinner, hugging it close to my chest to prevent it from flying off the counter. I slice the cherry tomatoes, mince the chives, and haul the buckets of ice into the front kitchen. Work is in full-flow when Peter, the head-chef, arrives. He is tall and tanned, with his hair spiked like a Chinese pop star. He berates Eric, half-joking, half-serious, for wearing his brand new sneakers in the kitchen. Then, at 11.45am, the lights turn on and the opening plinks of ‘Shape of You’ begin bouncing between the restaurant’s walls. It’s the first song of the day. It’s al- ways the first song of the day.

Aprons are donned. Peter goes through each station and starts yelling orders. Service starts out slow—a mushroom soup here, a salad there. The crowds ebb and flow. I begin to roll the pasta into spirals, then heat the soups. The crowds slowly build. Orders begin to roll out fast and small paper slips are passed between the chefs. Mid-service something will always run out—often it’s the pork sauce for the pasta—and I duck into the freezer and ferry a new packet of sauce to the worktops. Bursts of orange flame illuminate our faces. “Two salad out,” I shout over to Han, placing two bowls piled high with leaves on the service counter. “Oui,” he replies. The bowls are whisked away by the service staff as I return to the mounting line of orders. Glasses of green pistachio panna cotta are dished out. The freezer door is opened and closed. Often an unattended lava cake will erupt in the microwave. Eventually, the receipt machine falls silent. The chefs take a breather, or smoke in the parking lot. They giggle and play at impromptu arm-wrestling to fill the time.

I often went next door to the pastry kitchen to gossip with Fee. Unlike the other chefs, Fee is Singaporean and speaks both Chinese and English. I first met her when I was sent to retrieve the ice cream. Chatting to Fee soon became a part of my daily routine. Once, while she was stock-taking, she let me lick the pistachio panna cotta mixture off one of her spoons. To this day, it remains one of the best things I’ve ever tasted. “You never eat the panna cotta ah?!” she asks.

“No!” I reply, in Singlish, “You never let me try!”

She sighs dramatically as I ramble on about how amazing it was, and how I need to get my hands on the recipe, and how I want to know how she made it taste so good, and how she is a genius, and so on.

“Oh my god,” she says finally, pulling out a plastic container of panna cotta from one of the freezers. “If I give you some, you shut up, can?”.

Dinner service is more difficult than lunch because there are double the customers. There is also the salmon confit o deal with, which is tossed into the sous vide along with shredded fennel bulb and apple. Then, there is the increased number of orders of foie gras, for which you have to coordinate both the heating up of the lentils and the arrival of the foie gras itself—a delicate balance. Plating the salmon con- fit involves arranging three capers in a straight line, precariously balancing the salmon filet above it, and sprinkling an even layer of kombu flakes and minced chives over the fish—all while being careful not to spill any on the plate—be- fore inserting a shard of crisp salmon skin in the middle. This all becomes instinctive. Soon your muscles begin to remember your own movements and those of the chef beside you as he reaches towards the sauce, which you hand over.

The wave departs as quickly as it comes. Soapy rags are whipped out, pots and containers cleared, as the countertops are washed and wiped. First the soapy water is sloshed down from the outer to inner kitchen, then clean water, then clean water again. The floor is scrubbed and the excess water is pulled away into the drains. The chefs will remove their bags from their lockers at 10pm. There are four chairs in the parking lot, where they smoke, chat and recover from the day. They tell me—the new girl, the small Singaporean—that I don’t have to wait with them, that I’m a part-timer. “It’s OK, you can leave early”. I never say it, but I want to be a part of this group—Fee, Eric, Thomas, Han, Peter—and soon they realise, and give in. Over time, I be-come their younger sister. Every night I follow them out of the restaurant, as they make their way to the bus stop, dip- ping in and out of their lives and their banter. On the way, Thomas shows me pictures of the cakes he used to make, or Han and I will be involved in a poking fight. Peter will rant about how easy it would be to earn money with just one person working a stall: “that way, the money doesn’t get split”. He turns around and points to me. “Eh, Joy, you can just sell mushroom soup, onion soup, pasta. You can set up a small- er stall just next door… It’s good money you know, you can earn $500 a day just selling the soups and pasta. See, she’s considering!”

I laugh a lot at these conversations. Han will say, “Wah, you’re smiling so much,” to which I’ll make an exaggerated frown and the rest will laugh. Then they get the bus back to Malaysia and I’ll head for the train home.

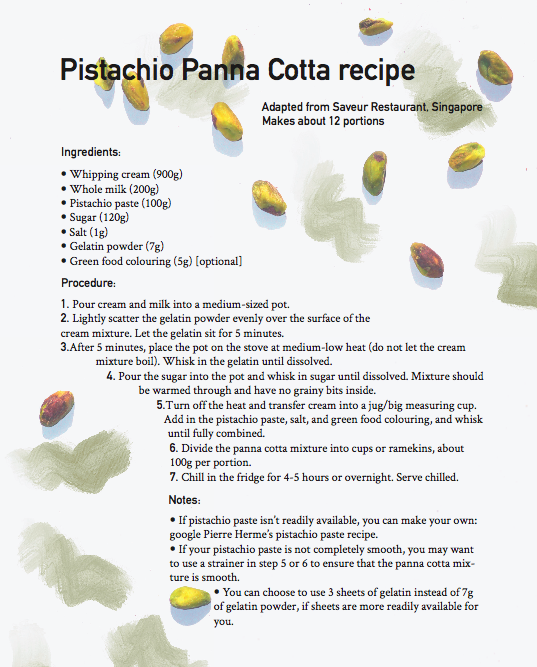

After two months working at Saveur, I told them I was leaving the job to go to university. I visited them twice after leaving, hang- ing around in the kitchen during their three hour breaks. Once, when I was sitting on the pastry kitchen counter, Fee gave me the recipe for the panna cotta. The recipe is still scribbled in my diary. When I began to drift away from Saveur, moving into new circles, meeting new faces—when I took a plane and arrived in Oxford in September to start afresh—this recipe became my lasting link to Saveur, to Fee, and to the moment I first tasted their pistachio panna cotta.