Battered Bodhrán

by Naoise Dolan | April 3, 2018

I worked at the Battered Bodhrán on Hackney Road. Six days a week, I’d come in at 7pm and leave shortly after we closed at one in the morning. They paid me seven pounds per hour, which added up to roughly a thousand a month, or nine-fifty after National Insurance. Of that, seven-fifty went on rent, utilities and council tax. The remaining two hundred was my oyster—small ‘o’, as I mostly couldn’t afford the tube.

Caoimhe had been working at the pub for a year when I arrived. Like me, she had no previous food and beverage experience but was hired for her accent. Men thought it was a sign we’d be interested in their Irish heritage—that, or they thought their Irish heritage was a way of making us interested in them. “What should I say to them?” I asked her during my first week. She said the easiest way to charm them was by appearing to listen. I’d been living on Wellington Row when we met, but a month later one of her flatmates left and she invited me to take their room on Ropley Street. “Save you a bit of time getting to work,” she’d said. I was grateful.

She had a boy, Tristan, a floppy-haired PhD student who was given to snorting coke off our kitchen table. “I wish he wouldn’t”, I said, and Caoimhe admitted she could see why it might contravene one’s conception of social graces. Tristan was five years older than her—twenty-one versus twenty-six—and brought her flaccid daffodils that she sprayed with perfume to cover the petrol station smell. I had no boy and no flowers. Considering Caoimhe’s setup, I felt this was for the best. He used her paracetamol when he was hungover so she had to borrow mine when her period came. She dressed in tight jeans and percussive heels when they went dancing on her day off, while he wore what he always did.

“Still no-one, Maria?” she’d say.

And I’d say: “I’ve enough to be getting on with.”

*

I had nothing to be getting on with. Saturdays with Rory were the highlight of my week. He came to the Battered Bodhrán and drank alone. His surname was Hegarty. I asked the questions I’d rehearsed with the other men who claimed Hibernian forefathers: where in Ireland were they from, when did they emigrate, or have you ever made it back to the old country, and I’d watch the level in their glass slowly fall until just a thin foam at the bottom. He said his Irish grandfather was a stage actor and had done well in London before leaving his (English) wife and five (English) children to run back to Dublin with a costar. He’d died in drunken obscurity, the grandfather. No-one else in Rory’s family had much time for mystic Éire, he said, not unreasonably given the circumstances, but he felt drawn to it and sometimes listened to Raglan Road to lift his spirits.

“It’s in a really nice part of Dublin”, I said, “Raglan Road. Quite posh.”

“I’d say it is.”

I told him there were embassies along it, the Turkish one for instance, and trees obscuring hulking Georgian townhouses. He could have found this information in a guidebook. Walking down it, you met with resistance: heavy wind, leaves to kick through. Hackney Road lacked texture by comparison. I felt like telling him that, but worried it would sound weird. London’s streets, I wanted to say, are easier to navigate, nothing blowing against you, nothing tripping you over—but with no elements to grapple with, just shouting and elbows, you start to wonder if you’re really there.

The first time we spoke, he’d been waiting for a friend who arrived after fifteen minutes. The next week, he came at the same time and day without a pretext. Eventually he asked which other days I worked and seemed amused, when I said every day but Sunday, to realise he’d been needlessly using up his Saturdays. After that he assigned the Battered Bodhrán, or me, the less valuable timeslots: Tuesday afternoons, Thursday evenings. It was upon realising I’d been downgraded to secondary billing that I first asked myself whether I found him attractive. Not bad, I decided: he had dark hair, pale skin and blue eyes, and I could already picture myself telling him his colouring was very Irish. He wore blazers with distinguished buttons and had a long, straight nose. There was enough to work with.

“I don’t want to be that guy”, he said one night, and I nodded to say: continue, be him. “I don’t want to be that guy”, he said again, “so here’s my number if you want to text me.” He wrote it on an old receipt. –

“Caoimhe”, I said the next morning, “what do you text guys?”

“Depends”, she said. “Tristan and I send each other memes.”

I made us both coffee. While the kettle boiled, I gave her my phone as though this would provide her with useful context, even though all it had was a blank message thread with his name at the top. ‘What do you talk about in person?’ she said. ‘You should make a joke about that.’

“I don’t know. Ireland, mostly.”

“D’auld country? Make an Irish joke, then.”

So I sent: “hey it’s maria sorry this is late, irish punctuality lol”. Half an hour later, he replied: “is irish punctuality a thing? haha didn’t know”. This made me wonder if Irish lateness was really a stereotype or if I’d made it up so my text would work. We ran through the preliminaries. I answered his questions about how long I’d been in the UK and what I’d studied at uni. In turn, he told me he was a first year foundation doctor—still a medical student really, he added in a follow-up message—at Homerton University Hospital. Then, presumably confident that he wasn’t being that guy, he asked what I was doing on Friday. Working, I said—I’d definitely told him that before—but I added that Sunday was my day off. We made plans.

*

Judging how much conversation I needed to extract was perilous: enough that I could have sex with Rory, not so much that he’d say something that would kill my inclination. “You’ve got such good skin,” he said. I judged this to be the point. Certainly, if I let him at it much longer he’d say something that would put the whole thing out of the question. Holding up a beer mat like it was a green card, I said: “What do you reckon?”

“About?” he said, but when I rolled my eyes he got it.

On the way to mine, I told him that the Irish were great talkers and that we preferred anything to silence. My voice sounded tinny and nasal, like it was coming from a phone on loudspeaker. “We can always spin out a conversation”, I said, knowing he could not be so immune to irony as to find this believable. Luckily the bar was near my flat on Ropley Street, even nearer than the Battered Bodhrán. Some of the faded shopfronts had been done up with monochrome paint and sans-serif fonts. “Gentrification,” he said. We passed a second-hand shoe shop called Second Tread and both agreed the name was clever. As we turned the corner, he tried to put his arm around my shoulders. I stopped him with just my eyes and was quite proud of managing that.

Our first mistake was going to bed before we’d undressed. I wanted to take his clothes off and have him remove mine—that was how people were intimate—but it was awkward to manoeuvre whilst lying down and in the end we both saw to ourselves. He was woeful at fingering but wasn’t bad on top. I faked coming, conscious that I was copying the noises Caoimhe made and that there was no way hers were real either, surely not from dandelion Tristan. She wasn’t back yet. I would have heard. I thought of her heels clunking on the floor, how the stilettos in particular were forever denting the wood in the Battered Bodhrán and how if nothing else this meant you could tell she’d been there. When I took the room, she’d hung up a picture of Glendalough. I noticed it was crooked.

He stroked my hair afterwards, Rory. I worried at first that this was his way of conveying he wanted to stay, but then he reached for his jeans.

“Are you okay?” he said.

“What?”

“You look a bit sad.”

Then he joked about my wallpaper featuring both cats and birds. It was ochre, and I told him the landlord had chosen a cheap, ugly one on purpose so he could raise the rent when the tenants inevitably replaced it. I had no idea if this was true but I thought introducing the topic would reposition Rory as someone who was once more not allowed to touch me. This status seemed heavy on his shoulders as he carefully closed the door behind him. A few minutes after he’d gone, Caoimhe came in.

“Not bad”, she said. “Cute.”

“He’s no Tristan.”

“Tristan’s not even as good as Tristan.”

I’d long given up trying to gauge whether Caoimhe was being sarcastic. “Why do you need him?” I said.

“What, Tristan? I don’t, really. The flowers are nice and it saves me the of hassle finding different people to go out dancing with.”

“What’s he like as a dancer?”

“Not bad. It’s one of the reasons I keep him on. Do you think—?”

“No, Rory’s not a keeper.”

“Ben won’t be happy.” Ben was our manager. ‘That’s a regular down the drain.’

“He’ll still come to the pub,” I said. “He has to prove to himself that it didn’t mean anything to him.”

“You look sad”, she said.

“I’ve heard. Can we watch some shit TV.”

We opened her laptop and found a dating show in Irish. The subtitles let us believe we understood everything and were only looking down at the English words out of reflex. Caoimhe picked sides, as she always did when we watched TV. The one with the ombre hair she could do without. Your man in the blue shirt deserved a nice girl, not the snipey ones he seemed to prefer. The absolute Aisling from Cork needed minding, so she did. None of the humour translated, which brought us back to the reality that we didn’t really know Irish.

“It doesn’t matter”, said Caoimhe. “Bodhrán is all you really need. That’s all the punters ever ask about. It’s music to their ears. Bodhrán na fucking bhFiann.”

“What’s ‘battered’ in Irish?”

“Fuck if I know. By the way, your picture’s crooked.”

I said to leave it, but she went and repositioned it so Glendalough stood at its proper angle. Then she looked at me. “Are you crying? Are you actually crying? Jesus, Maria, are you missing home?”

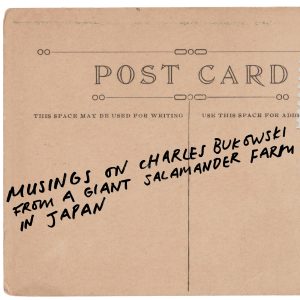

Artwork by: Issy Davies