Rap and the Regime

by Lily Begg | February 7, 2017

You stand naked and it’s so cold/ Daily rounds of torturing, hanging, shocking with electricity

Abu-Hajar wrote these lyrics on the first few nights of his imprisonment in Tartarus prison, West Syria. Arrested for spreading political pamphlets and singing an anti-regime song on the streets of his hometown, Abu-Hajar was told that his questioning would take five minutes. Two months later, Abu-Hajar and the rest of his band, Mazzaj Rap, were still being subjected to gratuitous and merciless torture. As other prisoners perished meaninglessly before them, there was no guarantee that they would survive.

His story began when he was young and in love. When the family of his girlfriend did not approve of their relationship, they invoked an entitlement which was at the heart of the Assad regime: an ‘honour crime’. The legislation justifies violence, torture and even murder of any allegedly ‘dishonourable’ individual. Abu-Hajar was submitted to four hours of torture and had no voice in court. This incident sparked his unwavering hatred of the Assad regime and a subsequent desire to voice this through rap music. A music born in protest against social injustice, the free flow and direct style of rap has resonated powerfully among the revolutionary Syrian youth. When I spoke to Abu-Hajar over Facebook, he was angry and pained about many things. When he spoke about music, all his rage disappeared; “music is an infinite ocean in which I find the nice waves not to surf over but to dive into.” The voice of the nightingale might be abrasive, but his song is exquisite.

However, the Assad regime has no patience for poeticism. As Assad’s force was becoming increasingly prevalent in everyday life by 2011, Abu-Hajar was becoming ever more active in his illicit political performances, choosing to be fearless in the face of certain punishment. He was imprisoned for several short spells before his unbearable two-month torture period, when he was finally released ‘conditionally’. Aware that he could be recaptured at any moment, and that his punishments would only increase in severity, Abu-Hajar made the decision to flee. One July night of 2012, Mohammad Abu-Hajar jumped over his garden wall and deserted Syria, the bosom of his childhood and the lifeblood of his music.

Today, Abu-Hajar would be instantly classed as a refugee, would have to wait for over a year for temporary asylum, and might never be guaranteed full civic rights, as well as being greeted by hostile and suspicious anti-immigration attitudes. Then, Abu-Hajar was accepted straightaway onto a masters course in Economics at the University of Rome. He intended to wait out the civil war, but as the situation only worsened, Abu-Hajar came to realise that it would be many years before he could return as a free Syrian citizen. Trapped in his exile, Abu-Hajar sought out a place where his political music would be listened to. He soon arrived in Berlin.

The German capital exerts an irresistible pull over alternative musicians. It is a place where musicians from all over the world meet, free to share and fuse different genres of music until all generic musical labels have been dissolved. Immediately immersed in this culture of alternative, undefinable music, Mazzaj Rap soon dropped their old-school 1990’s rap sound in favour of combining hip hop with innovative and non-traditional sounds. Abu-Hajar has even found a place for the piano, the instrument from his classical music upbringing, in his eclectic version of hip hop. He mixes melancholic piano chords, reminiscent of an innocent childhood, with the harsh stories of his adult word, all held together with a hypnotic electronic beat.

Unfamiliar with Arabic as a language and rap as a genre of music, I was surprised by Abu-Hajar’s unique ability to make his listeners understand him with the impassioned force which drives his every word. I was most taken in by his recent collaborative creation, Dialogue with Allah, as the music video is particularly striking. The setting of a grey, Germanic urban landscape is charged with the bright white cotton and the resonate indignation of the artists. The secular and barren setting of an abandoned airfield provides the space for a spiritual and political personal crisis. The lyrics express the disillusionment of the refugee who had sought ‘freedom’ in Europe, only to be faced with more injustice: “living here has taught me that bombs bring democracy/ so I’m asking you to teach me what real freedom might be”. Trapped in this paradox, he is further estranged from spiritual freedom, as he has led a faithless life: “what looks like political secret services is what they call religion/ that’s my defence tomorrow when judgement day comes”. Alone in the mortal dimension and shut out from an immortal one, there is no one to answer his questions. His voice rings out unanswered across the airfield, and the single dancer is doomed to spin in slow circles to the repetitive pulse of the piano, until the scene fades to darkness.

Despite the pervasive anger which fuels his music, Abu-Hajar has transformed this emotion into something uncommonly poetic. When I asked him about what it felt like to perform, he replied: “I feel like the stage is on fire. I’ve lost many things and I don’t have my own home, but the stage gives me this temporary shelter where I feel I belong. I feel so rooted to the floor yet so light that I could touch the ceiling, I feel like the drops of sweat are discharging my rage as they fall.” Although all of his lyrics are written in Arabic, the power of his meaning is never misunderstood by his mixed nationality audiences. He even refuses to see his followers as fans; they are “an organic part of the Mazzaj experience.”

Although his fame continues to grow in Germany as he regularly goes on tour, works with international artists and has succeeded in creating an original and versatile style of rap, Abu-Hajar is not a musician. He’s a protestor. Since being in Berlin, he has been a leading activist in the city, rallying hundreds of civilians to march by the Brandenburg Gate last year to mark the fifth anniversary of the revolution. However, Abu-Hajar remains cynical of the Western approach to ‘solidarity’. He explained to me the mentality which he believes to be residual of our colonial past; the involvement of the West in Syria is based on the prejudice of Syrians being “less civilised people” in need. He used an example from the recent Civil March for Aleppo, where he was shocked by the event organiser’s attitude towards the Syria conflict: “she didn’t know who was killing whom in Syria, as the reasons why people are fighting are irrelevant; all they need is her presence in order to achieve peace”. Even NGOs are guilty of this colonial approach, for “they think that the single reason for our suffering is a low level of development and that’s it; with a bit of female empowerment and more education, things would be resolved. They totally ignore the fact that people are seeking freedom from a regime.”

Mazzaj Rap’s latest project, Raboratory, seems to encapsulate their experience in Berlin. Hajar describes it as “mixing rap with oriental Taksim music”, which challenges both the sonic traditions of the Middle East as well as the ability of rap music to be accommodating to foreign sounds. The album will be called Third Culture, as he hopes that the result will defy definition as either Western or Middle Eastern music. “There will also be a new single called Uncertain State in which we address the uncertainty of our lives in exile and the uncertainty of the state of Syria.”

Abu-Hajar might have reclaimed his freedom of expression in Berlin, but life is still not free from humiliation. For a place which boasts “Refugees are Welcome” signs on every street, the rise of far-right popular movements such as PEGIDA continue to normalise racist attitudes. He said to me that the same day that Bashar Al Assad is down, along with his regime, he will return to Syria. “I want to participate in building a new Syria that respects the dignity of all people regardless of their nationality, ethnicity or social background.” For the time being, Abu-Hajar will sing his nightingale’s song to German audiences, but he will always have one eye on the horizon, waiting for the storm to pass.

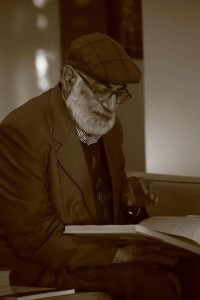

Photo: Abu Hajar