Nombrilisme: Thoughts on the Belly-Button

by Sophie Eager | January 1, 2016

‘Nombrilisme’ (masculine noun, French): an attitude of self-absorption, when a person believes that everything revolves around or relates back to them

‘Se prendre pour le nombril du monde’: to consider oneself as the centre of the world.

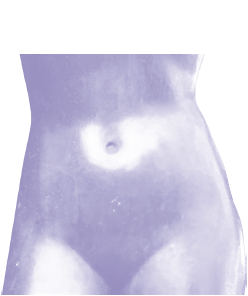

In his short story The Apologizer, Milan Kundera’s protagonist Alain meditates on the navel as he observes the naked stomachs of the young girls on the street around him. He is captivated by them. Kundera posits that the part of our flesh we choose to most obviously expose says something particular about the erotic orientation of our time. Alain reflects that leggy girls with long bare thighs are the metaphorical image of the fascinating road that leads to erotic achievement, always reminding us of the lure of the inaccessible. Similarly, chesty girls with exposed cleavage suggest sanctification of the woman, “the Virgin Mary suckling Jesus, the male sex on its knees before the noble mission of the female sex”, as Kundera puts it. But now Alain sees girls with their navels obviously exposed, and is unable to improvise an answer for how to define the sexual orientation of an age that eroticises this newly bared bit of the body.

Once you start noticing belly buttons, they are hard to ignore. Funny little knots right in the very middle of the body (check Da Vinci’s Vitruvian man); sticking out, twisting in; a symbol of both the freedoms of the sexual revolution and of our umbilical tie to the mother. But they are also a sign of nombrilisme. Nombril in French, like ‘navel’ in English, is a word both for the centre of a physical space and for a belly button. So nombrilisme, translated as ‘navel-gazing’, is the word the French have for the attitude of seeing one’s self as the centre of everything, as the navel of the world. But in 2015, exposing your belly button has also become a symbolic act. The bare belly button is a distinct kind of nakedness that says something significant about our generation’s attitude to the self. The act of its exposure has a different message: a defiant self-centredness.

A belly button, unlike the curve of a breast or the line of a thigh, is isolated from the continuous lines of the rest of the body. It is exactly where something has been cut off, a constant reminder of the vital link to our mother that bought us into existence, which is now severed. It is a scar of separation, and actually looks quite strange when observed up close, like the tie in the end of a party balloon. The combination of its exposure and its oddity inevitably draws the eye.

In Hollywood films of the ’50s, the strict Hays Code enforced firm rules on what could not be shown on film flesh-wise. But as hemlines and necklines receded, navels remained taboo. In the 1955 film Land of the Pharaohs, Joan Collins’ bare button had to be filled with a large ruby to get her belly dancing scenes past the censors. Marilyn Monroe, whose plunging dresses exposed all parts of the body bar the navel, wasn’t allowed to expose hers on film until Something’s Got to Give in 1962, when she drily noted, “I guess the censors are willing to recognize that everybody has a navel”.

Next came the power pop females of the 90s. Madonna through Shania, to J-Lo and Christina Aguilera rocked bare belly buttons. Britney Spears’ bare navel even earned her a hot-under-the-collar article in the esteemed Encyclopaedia Britannica in 2001, which described it as “a heated boundary between baby and babe… halfway between head and genitalia, not strictly sexual, but – like Spears herself – ‘not that innocent’ either…” Despite some flustered semantic guff, the essence of the article is coloured by the same confusion that Kundera’s Alain experiences. The belly button is sexy, but also childish; neat and taut, yet disconcerting when viewed up close.

This was quite a long time ago now, but wearing a crop top in a Parisian club still earned disapproving hisses of “anglaisssseee” from my fellow revellers. I found this curious, because the French language seems to encourage nombrilisme. Any enunciation can plausibly start with the double personal pronoun: “Moi, je”: “Moi, je crois… Moi, j’y vais…”, ever faithful to the Cartesian foundation for the source of all certain knowledge as yours truly, the thinking self. ‘Moi’ is the figure of this inward movement, with its own navel in the smug middle ‘o’, the curve of its diphthong turning the enunciation in on the speaker. I see the exposed belly button as a symbol of this disjunctive pronoun, its nakedness prefiguring the self-centredness of subsequent actions by the subject.

However, the all-pervasiveness of social media has now made self-centredness entirely standard, providing an accepted and widely used platform for self-promotion and external validation. Equally, its very visualness has shifted new significance onto our bodies and changed how we present them, an effect that can be hugely positive when well-directed in campaigns like #freethenipple. Yet the same mood also entails streams of gym selfies, bikini beach photos, #eatclean, #fitspo, #abs. The issue with the world revolving around your navel is that it requires devoting a significant proportion of your free time to get that navel ‘in shape’ in the first place. A navel ready to be exposed actually takes a great deal of self-centric work. So to be able to present the bare belly button, our world actually starts to revolve around the navel; we gain our sense of self-worth from its attractiveness, it is a sign of our achievements and the culmination of our goals. And this means people are looking great – but they are not necessarily doing good.

Is this worrying? Like Kundera’s Alain, I am still confused. The navel has served its biological purpose long before we even come to have a concept of ‘me’, and yet we now choose to spend so much of our time making our navels look as good as possible to prove how wonderful we are too. This dedication is ostensibly harmless, even admirable, but it seems a shame that it has been elevated to such a high level of importance. We are losing time for putting other, worthier things out into the world. I point no fingers; I too am partial to a crop top. But the nagging nasals of nombrilisme persist; look beyond the belly button and find another, nobler ‘navel’ upon which to gaze.