Laurel and Sausages: ‘The Anachronistic Procession’ Unmasked

by Miranda Devine | July 12, 2023

Spring arrived in German country.

Over ash and rubble

The first green of birch unfurled

Tentative, delicate, and bold

Out of the villages, as from the South

A tattered procession of voters went forth

Who carried with pomp,

Two old banners.

The stitches were ragged and worn

And the inscription faded

And it was something like

Freedom and Democracy.

The beginning of Brecht’s 1947 satirical ballad, ‘The Anachronistic Procession, or Freedom and Democracy’, evokes an absurdly literal image of the poem’s idea of anachronism. Set in post-war West Germany amid the rubble of the old regime, Brecht places old and new in the landscape of hope for regeneration. His poem imagines a parade of voters marching through the country, crying out for a new era of US-style “Freedom and Democracy”. The procession forms a panoramic vision of all those who now are unified in calling for this change, who include all areas of society: from the civil service to the Church, to Parliament. But the outdatedness of the procession is made disturbingly clear when the figures marching for change are revealed to be those who were complicit in the former regime, having whitewashed themselves and disguised the past through thinly-veiled cosmetic changes. The effect is haunting:

Follow, because the state needs them

All the de-Nazified Nazis

Who as lice in the cracks

All sit in high offices.

When I first encountered Brecht’s poem, I was struck by the strange power of the procession. As a vehicle for depicting the characters and symbols in a moving performance, the procession provides a unique opportunity for unmasking the ‘real’ workings of society. It can come in a variety of different characters from a religious or civic parade to a military triumph or political march, to the festive procession of a carnival. Likewise, it has the power to include a wide variety of participants and symbols within one spectacle. Just as a real procession congregates disparate individuals as participants, so, too, does the literary procession have the ability to draw together and impose order on the otherwise disconsonant and chaotic field of meaning.

It is perhaps this ability of the procession to carry, order, and display a multiplicity of meanings that has allowed its message to have been felt in so many different contexts. Brecht’s procession may be “anachronistic”, but it still carries forth its ideas with an enduring resonance. This was clearly felt in the ‘80s and ‘90s when the poem was adapted into a political street theatre performance of the same name as a warning against the nationalistic tendencies in Germany after reunification. Still today, ‘The Anachronistic Procession’ remains relevant in our own society; the recent coronation of King Charles III can be understood as a pageant which also had a deep interest in anchoring the present in the authority of the past. Much of the pomp of the occasion – the gold state coach, the standards, regalia, the ‘sword of destiny’ – sought to add a layer of archaising tradition and mystifying symbolism to the ceremony. This performance of meaning and spectacle of supposed solemnity exemplifies one reason for the importance of understanding the procession and why it represents a valuable mode for the satirist.

Brecht was not the first to draw on the procession as a literary motif. Pageants had been used by English Renaissance writers like Spenser and Marlowe as a focus-point for considerations of hierarchy and order, while in 19th century Italy, the Risorgimento movement calling for Italian unification saw the recurring appearance of the procession trope in the narrative literature of the movement. But the greatest influence for Brecht’s poem comes from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1819 poem, ‘The Masque of Anarchy’. Shelley’s poem was a response to the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester, when a crowd peacefully protesting for the reform of parliamentary representation were charged at by cavalry, resulting in 18 dead and 400-700 injured. To evoke a panoramic vision of England and the powers that had enabled the charge, he used the form of a parade to depict this “ghastly masquerade”. The real figures complicit in the massacre are disguised as the personifications of Murder, Fraud, Hypocrisy, and Anarchy, who ride in riotous triumph through the country like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Brecht hailed Shelley’s poem as an exemplar of “historical realism,” which allowed for the ‘reality’ of society to be unmasked through a highly symbolic depiction of the world.

Brecht’s poem is also highly figurative, but he seems to expose reality in a different way to Shelley. Brecht’s drama is well known for its Verfremdungseffekt, or defamiliarisation effect, a technique which seeks to create a sense of alienation and distance between the audience and the performers in order to place them in the position of consciously detached observers who could question and analyse the reality they saw. Perhaps something similar is going on here: the inherent performativity of the procession, with its performing participants and onlooking observers, creates the detachment needed for this unmasking. While the literary procession might often try to impose order on the disordered, ‘The Anachronistic Procession’ seems to revel in the strange and absurd incongruity that refuses to fit neatly together.

Out of the disordered and multitudinous mass of meanings and associations being carried along in ‘The Anachronistic Procession’, perhaps the most interesting is that of the festive and carnivalesque. The custom of a carnival has varying definitions and traditions within Christian and Pagan cultures. Common elements include parade, disguising and masking, theatricality, and the temporary dissolution of established hierarchies and standards. Accordingly, the Carnival was interpreted by the Russian literary critic Bakhtin as a social institution that “uncrowns” the higher functions of thought, speech, and the soul by translating them into the “grotesque body”. The grotesque here can be viewed as a style of bodily excessiveness and exaggeration, with a particular emphasis on body parts which protrude or open, bodily fluids, and acts like laughing or cursing, which “allow in” the outside world into the pure body. The poem’s semantic field of laughing, loud singing, bursting, hatching, hanging, swinging, writhing, and formlessness echo Bakhtin’s ideas. While the procession of Shelley’s ‘The Masque of Anarchy’ is carnivalesque in its festivity, freedom, drunkenness, and the confident comfort of Anarchy “who bowed and grinned to everyone,” Brecht’s poem goes far beyond into the recesses of the grotesque:

Blood and filth in the elective affinities

Marched through the German countryside

Belched, vomited, stank, and cried

Freedom and Democracy.

In Shelley’s poem, the English countryside is almost mythologised as it takes on the role of solemn witness to the protests of the people. Here the German countryside is placed in quite a different position.

The festive and carnivalesque nature of such grotesquery climaxes towards the end of the poem when six figures emerge from the old Nazi headquarters and join the procession in six coaches. These figures (or Party Members) are named similarly to the personifications of destructive forces in ‘The Masque of Anarchy’, as the reifications of evil: Oppression, Leprosy, Fraud, Idiocy, Murder, and Robbery. They ride by in a highly performative spectacle of comfort and bodily pleasure, revelry, and leisure; the ease with which they play their role is sinister:

Behind him rides Fraud

Swinging a great tankard

Of free beer. To have your fill

You only need to sell him your children.

Hanging an arm out the side of the car

Murder drives up,

The brute sprawls out to his comfort

Singing: Sweet dream of liberty.

The excess, the melodramatics, and the pleasure they take in their farcical performance all grossly exhibit the cynical actor’s own awareness of the fiction. The result is surreal, absurd, and alienating in its strangeness.

The nature of this procession’s identity is discordant and disorientating, but the carnivalesque perhaps provides a way of uniting them. At first glance, ‘The Anachronistic Procession’ appears to be a political procession with its voters, banners, and rallying cry for “Freedom and Democracy,” but the vast field of symbols and characters in the parade also include religious characters as “two stepped by in habits / Carrying a monstrance past”. A civic suggestion is indicated by the participation of civil servants and professionals of the former state, such as teachers, physicians, scholars, newspaper editors, judges, and even the SS. The loud singing of the Western Allies’ parodied anthems also points to the civic:

Allons, enfants, god save the king,

And the Dollar, cling, cling, cling

Then, towards the end of the poem, they finally arrive at the bank of the river Isar, “the capital of the movement”. This was the site where the ashes of several convicted Nazi war criminals, including Göring’s, were scattered following their execution in 1946. Revisiting the site of the dead implies that this represents a funeral procession, an idea reinforced by the singing of a requiem at the end as a hearse is driven behind the six figures carrying “an unfamiliar breed”. Given the carnivalesque notes in the rest of the poem, there is a potential implication here that this is similar to a festival of the dead, in which participants seek to bring back the dead for a period of time. Finally, the threatening undertone of a military march emerges at the end of the ballad when the figures of Oppression and Leprosy ride by in armoured tanks as if celebrating in triumph. The anarchy of meaning here is supposed to be overwhelming: the procession may try to impose order on reality, but in this instance perhaps the point is that the reality doesn’t make sense.

Revelling in a surreal mix of high and low, fact and fiction, ‘The Anachronistic Procession, or Freedom and Democracy’ is well summed up by the poets of the ballad:

Artists, musicians, princes of poetry

Screaming for laurel and for sausages

Their initial demand for laurel is high, solemn, triumphal, cultured. The sausages that follow – the low, reconstituted flesh of a carnival – is the grotesque reality.

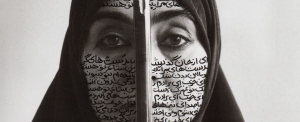

Words by Miranda Devine. Photography by InChan Yang