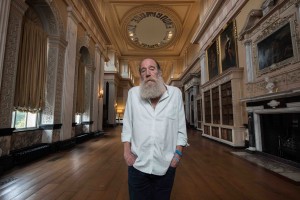

On Hew Locke’s The Procession

by Millie Dean-Lewis | May 10, 2022

The viewer does not walk with The Procession on arrival, rather against it. The work, by Hew Locke, is a vast installation: a protest, a carnival, and a funeral march all in one, composed of around 130 figures who travel from the back wall of Tate Britain’s Duveen sculpture gallery to meet its entrance. Constructed in patchworked cardboard and adorned with thread, hessian, and pearls, these uncannily realistic adults and children walk alongside humanoid forms and people on horseback. Leopard skin permanently gloves hands; medallions, ships, and animal heads are found in place of human ones. Screen-printed fabrics — in an eclectic collection of greens and blues and pinks and yellows and reds — provide a rich variety of socio-political symbols that underpin the work. Centrally, the work draws on three imminent crises: increasing numbers of refugees, the continuing effects of colonialism, and the threats of climate change. A cross-cultural and transtemporal jumble of histories, it relies firmly on temporospatial relations which nominate the future as in front of the present, and the past as behind. The Procession, tackling definitional anxieties surrounding terms such as ‘post-colonial’, suggests a forwards movement that relies not only on a recognition of the past, but also on an awareness of its lasting effects as experienced in the present.

With reference to on-going and historical forced migrations, the work is imbued with an infinite and kinetic quality. Screen-prints on expansive sheets of cloth punctuate the artwork as flags and banners and capes, and the viewer journeys seamlessly from the early 20th century Turkish-Greek war to modern-day refugee camps in Greece, caused by the war in Syria. Modern comment on a conflict-induced displacement of people, on coerced voyage, is further insisted by model boats that overwhelm the heads of a series of figures, acting, in some sense, as figureheads. Alongside share certificates for the Jamaica Trading Company, a railway construction company in India, and gold mines in Nigeria, these symbols serve to spread the viewer about the world, and they themselves become an object of relocation. An Atlas-like figure who ends the piece broadens the physical scope of the work even further: this Titan, condemned to hold up the heavens for all eternity, stands on the very edge of the earth. The viewer is met in their present moment by a share certificate for the Russian General Oil Company, pasted onto the skin of a drum held by one of the procession’s leading figures. In this way, extremes of place and time bookend the work, and it expands limitlessly across tragedies.

The piece’s migratory note is not entirely doomsaying however, where the movement inferred becomes less literal. There is a child, for example, stepping forwards with all the others, whose left foot is about to tread down on a flag draped onto the floor by a figure in front. In the paused moment that Locke has created, the viewer knows that the flag will be moved forwards as its carrier travels, preventing any stalling – Locke here demands a collaborative movement, acknowledging the possibility of futures characterised by trial and tribulation, but ultimately drawing the viewer away from them. Any references to refugee crises that the world currently faces are balanced by a forwards glance to more uplifting futures.

Post-colonial elements are equally balanced, complex, and plural. Across flags and blazer backs, a repeated image of the Parliament Square statue from Locke’s 2008 work Churchill, greatcoat gorgeously defaced, harkens now to Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. A similarly embellished image of Queen Victoria (Hinterland, 2013) alludes to an era of British colonisation in India. Velásquez-esque dresses drawn wide with panniers and covered in mournful black cloth hint at dwindling monarchist traditions that reach back even further. By playing with familiar images from his own body of work, as well as diverse symbols of various pasts, Locke’s piece collapses centuries of colonies and their colonisers into a singular artistic event.

With this extreme condensing of peoples and places arises the opportunity to highlight self-contradiction inherent to a society, and the all-too-easy tendency to reduce such a multi-layered existence. This contradiction, arising from an essential plurality, is not to be hidden nor smoothed out. One object, requisitioned from a colonial side is John Singleton Copley’s The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781 — a piece also on display at Tate Britain. It is rendered in Locke’s work in cut-up sections, pasted on an object that seems a cross between a vehicular litter and a coffin. Teetering symbolically between reverence and destruction, the inclusion of this painting in which a black slave faithfully seeks to avenge his master’s sniper reveals an act of appropriation. This commandeering, then, exemplifies a distancing from dogmatic colonial narratives, and highlights the understandable uneasiness of a post-colonial piece that itself relies on the Tate Britain, of all galleries. Founder Henry Tate, whilst never a slave trader himself, made his money from sugar plantations in the Caribbean that depended on the legacy of slavery. The Procession, situated in such a proudly derivative neoclassical gallery, seems acutely aware of these facts, and the space and its commissioned work carry within themselves contradictions of identity that are here forced into constant dialogue with one another.

Looking beyond this reconciliation of difficult and complex histories, present predicaments make themselves known in images evidencing the rising of sea levels. These climactic references are pragmatic as well as theoretical, as the work’s physical composition appears relatively sustainable. With its figures predominantly constructed from recyclable materials, its clothing largely second-hand, there is not only an acute awareness of a crisis at hand, but a helping hand offered in practical response. In a piece that reminds of Lubaina Himid’s Naming the Money, metaphorical reusings of Churchill and Hinterland are accompanied by a group of figures who wear clothes physically repurposed from Locke’s 2015 piece The Tourists — most clearly a pearl-encrusted red jacket and a hat embellished with skulls. There is an overlapping of theoretical and literal borrowing that, despite its constant acknowledgement of persistently dispiriting issues, allows the work to be at times active in its stances, progressive, and motivational.

When walking back through the piece, the viewer joins not only The Procession, but a suggested societal progression too. Now travelling alongside the rest of the figures that take up space in the gallery, the presence of a handful of figures in the work that do not face forwards and out the door becomes clear. Most are children. One, maybe halfway down the procession, is a body in patchworked green who, owing to their countermotion, appears lost. Another, in white mesh and cardboard, clearly turns back to take the hand of a parental figure. These younger, less experienced members of the march now come to function as past instances of the viewer, who, now older, is wiser for taking a plural past with them. Locke’s work recommends both a marching forwards and a looking back, with strides and glances spanning continents and centuries.

The Procession is on display at Tate Britain until 22 January 2023.

Words and art by Millie Dean-Lewis.