Medieval Clowns in the Style of Matisse, and Other Works Not By Me

by Beatrice Ricketts | June 22, 2023

Choose any subject matter, any medium, any colour palette, any artist’s style. Now go!

This is what DALL-E offers. A ‘text-to-image’ generator, this artificial intelligence programme is for images what ChatGPT is for text, and it is unsurprisingly blaring a big Code Red in the art world. Type in a prompt and receive results within seconds. Depending upon your instructions, the images can range from simple cartoons to disconcerting photorealism.

DALL-E’s speciality seems to be imitation. Visitors of the site are immediately lured in by comedic prompts to challenge the system with requests for renowned artists. ‘CLICK TO TRY: A sea otter with a pearl earring by Johannes Vermeer’, comes up first on the homepage. It turns out to be quite an amusing picture.

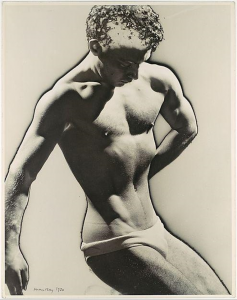

I have to give it a go myself. For my first creation, I type out something I think I would like: ‘an oil painting of a bookshop in Vermont, at dusk, in the style of Edward Hopper’. Within ten seconds, DALL-E has spat out four options for me.

[An Oil Painting of a Bookshop in Vermont, at Dusk, in the Style of Edward Hopper, prompted by Beatrice Ricketts. Artwork by DALL-E / Courtesy OpenAI]

Admittedly, these images are beautiful. They are the Hoppers I secretly wish he’d done. They are also right on many accounts. The empty streets create that melancholic ‘Hopperesque’ mystery, and the painting brushwork (if I may call it so) is suitably smooth and simple. Knowing this was made by artificial intelligence, though, my eye keenly roams to spot incongruities, which are not hard to find. There are obvious problems. In my favourite of the four pictured here, the figure has no face, merely a thumbprint shaped head, and the books look more like the splats of a Jackson Pollock. A more subtle point (which clearly evades the computational aesthetics of AI) is that you’d be lucky to find such warmth in an actual Hopper. The darkness of ‘Nighthawks’ is illuminated by a cool, almost bleak lemon, but here, the light radiates out of the bookshop like a comforting golden hub in the dusk. Such minutiae of mood are arguably what makes a Hopper a Hopper.

Maybe I would have liked the real artist to paint something like this; it would be a breath of optimistic air in his sombre oeuvre. But I know it is artifice and feel like a phoney for quite liking it. It’s a pretty picture, but could I genuinely put this up on my wall, knowing it was made by a computer program? Even if it were perfectly accurate – which I don’t doubt the future developments of such generators will be – there’s no thought behind the painting, no mood, merely pixels.

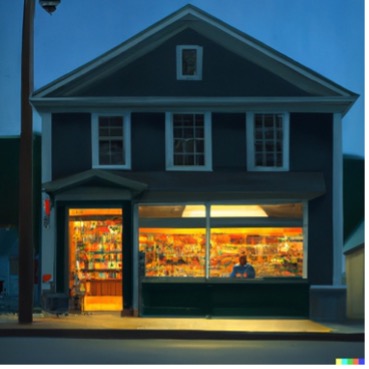

In a more complicated attempt to trial my AI friend’s powers of creation, I test out ‘a pastel drawing of four clowns in medieval robes playing chess in the style of Matisse’.

[A Pastel Drawing of Four Clowns in Medieval Robes Playing Chess in the Style of Matisse, prompted by Beatrice Ricketts. Artwork by DALL-E / Courtesy OpenAI]

This is less immediately concerning than the Hopper, and more amusing – I can confidently say there’s no question of my wanting to frame these bizarre images. What DALL-E has churned out for me is certainly the style of Matisse; it is less so his usual subject matter, of course. But such dismissive remarks are perhaps too confident. If a new exhibition titled Matisse: the Lost Clown Years debuted at the National Gallery, purporting to have found a series of medieval clown paintings which had never before seen the light of day, we might not even question that they were his. We might nod in appreciation. It seems that these programmes highlight the often-arbitrary contextual features which we use to define art. Although a visual form, it is not just what we see that dictates what we like, but who made it and why.

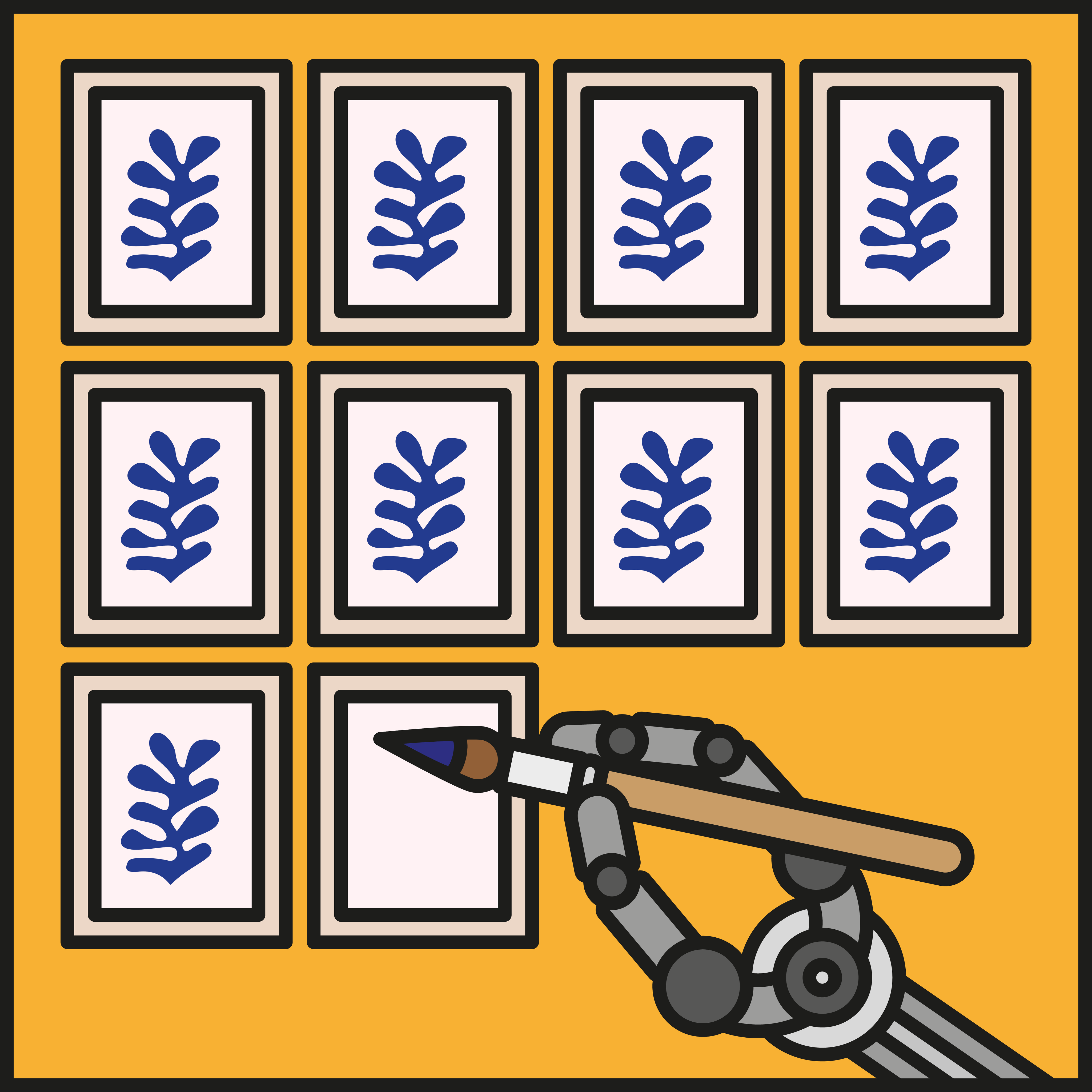

Now I have my own Hopper and my own Matisse. And I can confidently say ‘my’. As boasted by the company’s name, OpenAI, these creations are truly ‘open’; anything I create using this generator is legally mine to distribute as I wish, be it plastering the image onto a t-shirt or using it in an article. These programs unsurprisingly burst open a Pandora’s box of ethical issues. This Silicon Valley company, responsible for both DALL-E and ChatGPT, which numbers Elon Musk amongst its co-founders, proclaims on its website the lofty mission statement to develop “friendly AI” that “benefits all of humanity”. To uphold this goal, the creators have focused first on the names of their robot offspring. They have slapped ‘Chat’ in front of the more clinical ‘Generative Pre-trained Transformer,’ whilst the name DALL-E is a playful portmanteau of Dalí and the anthropomorphic Pixar robot WALL-E.

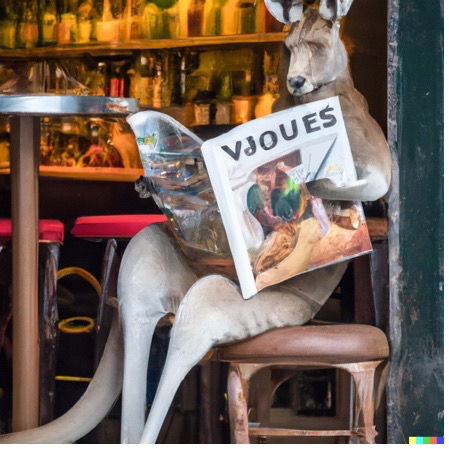

Despite their inviting names, the implications of this technology are worrying. The magical accuracy of the generators is the result of their being trained on millions of images pillaged from across the internet – sources which will unavoidably include living artists and copyrighted images. Requesting a Rembrandt painting of a burger, if that’s what you’d like, seems harmless; the artist in question happens to be long gone, and will not be calling up for royalties anytime soon. For many DALL-E creations, though, the information harvested is more troublesome. Intellectual property is a tricky and capricious territory: ask for Mickey Mouse in the style of Lichtenstein, and there he is. Ask for Vogue magazine, and the text on the cover is carefully distorted to say ‘Voogu’ or ‘Vogouo’.

[A Kangaroo in a Bar Reading Vogue Magazine, prompted by Beatrice Ricketts. Artwork by DALL-E / Courtesy OpenAI]

Artists are now spiralling into an existential crisis, fretting that their work is being stolen without consent, and piling up lawsuits. Yet AI is made to impersonate humans, imitate their speech patterns, and copy their art. Maybe this encyclopaedic feature is just another facet which reflects our own minds. When we walk along the street, visit an art gallery, or scroll on a phone every image subliminally enters the library of reference inside the human mind. This is exactly what is happening in the mechanics of DALL-E.

Even if there is explicit influence from another work evident in an AI creation, ripping off someone else is no new development between artists. There would be no Caravaggio without Titian, no Sickert without Degas. Am I forging a Hopper, or being innocently influenced by his style in my own work? Our dystopian fear of the unknown may be insularity, discriminating against a new method of art formation which is just an upgrade of the old. We draw an indignant line between positioning a subject behind a camera lens and writing a prompt into a program because we distrust artificial intelligence. Yet, in neither case have we personally created what is in the image (as with painting) but have simply chosen it.

Regardless of whether we believe the work of artificial intelligence to be on par with human creativity, it is already infiltrating the gallery space. A recent exhibition at Gagosian in New York, from March to April 2023, consisted of eerily indescribable DALL-E images which were made to look like nineteenth-century sepia photographs. Another artist, Charlie Engman, exploits the uncomfortable artifice which plagues AI art through truly bizarre tableaux. Humans twist into biologically impossible positions to kiss in car parks, children sit next to horses whose legs morph into sofas, and the artist’s own mother’s face sticks sombrely out of a large melting wheel of brie. Engman, using Midjourney – another popular generator – demonstrates a computer’s fundamental lack of understanding of reality with these malformations. This is strangely comforting. We are reminded that not only can computers make mistakes, but that the product of these programmes, like the Vermeer sea otter, can be harmless.

I spoke to the Brooklyn-based Engman over the phone, and he told me that he is “interested in embodied states and what it means to represent physical realities”. Midjourney is exciting precisely because “it is so divorced from physical reality”. Where these programs succeed then, it seems, is when the artist can acknowledge and embrace the fact that they are not human. Artificial intelligence is not limited merely to a mediocre imitation of what humans have already achieved with their own hand; its extraordinary abilities can rather be used to create a hybrid of the real and the unreal, a nonsensical strangeness which the ingrained logic of the human mind would not otherwise allow us to explore.

I asked Engman if he believed there was any hierarchy between art forms. This may have been a faux pas. “No!” he hastily exclaimed, “This is a hill I will die on!” He suggested that art enables the experience of information, and that the “substrate” (painting, photography, AI) computes this information. If this substrate is independent from the subject, then it does not matter what the medium is: the experience should be the same. Or so says Engman.

I find it hard to divorce context so assuredly from art, and here declare my hand as an AI art sceptic. The defining aspect of the artificial intelligence revolution for the art world seems to be that it is simply scary, with the scale of development surpassing human ability to accommodate it.

For the time being, though, we might as well make some absurd pictures on a website.

[A Salvador Dalí Painting of a Golden Retriever Eating a Burger, prompted by Beatrice Ricketts. Artwork by DALL-E / Courtesy OpenAI]

∎

Words by Beatrice Ricketts. Cover art by Dowon Jung.