A Feast for the Eyes

by Imogen Whiteley | March 18, 2020

Still Life with Fruit, Jacob van Walscapelle, c. 1675

1. Against a tastefully dark background, colours look richer. The edge of a crystal wine glass stands out more sharply, a pomegranate seems redder, the bloom on the midnight-purple skin of a grape looks softer. This is what food is in seventeenth century Dutch still life painting – ordinary objects made into monuments. Of course, such a painting is never just about food. Food in images like this becomes a symbol of the wealth, sophistication, and piety of the painting’s owner.

The idea of food as image, as symbolically-loaded art object, is not unique to the past. Food photography on Instagram uses a similar aesthetic language to that of the Dutch still lifes, and the messages are similar too. These days, we don’t need to commission a painting to create an impression of a desirable life. A social media profile is the perfect vehicle for conspicuous consumption. The food we choose to eat indicates what sort of person we are.

The juxtaposition of highly-aestheticised images of toned bodies with images of food on the accounts of popular bloggers makes the link explicit: if we can’t be the ideal woman of our choice, eating like her is almost as good. Following a logic of optimisation, we alter our online image in accordance with the demands of the marketplace. It is now possible to embody the ideal, at least virtually. Food facilitates this manipulation of online self-presentation. By posting images of food deemed ‘clean’ and ‘guilt-free’ – usually meaning low-calorie, prohibitively expensive, photogenic – we atone for not being perfect ourselves. In the world of #cleaneating, verdant curls of spinach and spiralised courgette say ‘I am sophisticated and disciplined enough to prefer eating this to pasta’. Elaborately sliced avocadoes announce ‘I am wealthy enough to have time to do this myself, or to pay someone to do this for me’. Platters of vegan, flourless, oil-less pancakes and biscuits and cakes suggest that even our indulgences need curating. These luxuriant, over-filtered images of food as still life are undoubtedly beautiful, but they are hollow. What’s transmitted is not an impression of a sensory experience, but a message about status and morality. I find these photographs mesmerising, spending far too long scrolling, thumb sliding over each smooth glassy image. It’s hard to tell whether it’s the message or the beauty of its presentation that is more appealing.

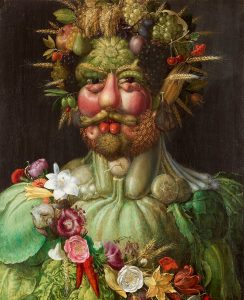

Vertumnus, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1591

2. Every January, diet and wellness culture re-enter our lives in the aftermath of holiday indulgences. Immediately following a period where we as a society engage with the social and sensory side of food, we are bombarded with messages about the state of our bodies. We’re sick, we’re told. Bad food is contaminating our bodies, making us fat and sluggish and stupid. The way to fix this is a juice cleanse. We’ll come out the other side with glowing skin, lithe bodies, and newly productive, efficient minds. Eating the right food will heal us, will re-compose our bodies and souls. It’s not always a juice cleanse, but it’s always pseudo-religious. The exact method varies depending on the ideal self being imagined – for tech bros intermittent fasting becomes ‘biohacking’. Fast like a 14th century saint, accepting only the pre-blended eucharist as ordained by your particular sect, and you’ll be reborn into shiny-haired eternal life.

The spectre of wellness culture makes it difficult to enjoy indulging. The prestige implied by having a perfectly ‘clean’ diet can mean eating becomes loaded with implications about identity. Eating healthy food in itself isn’t the problem, of course. It’s the attitude of purity that permeates clean eating and wellness culture, rather than the food itself, which is harmful to our cultural relationship with eating. In the theology of diet culture, food sins become moral sins.

We fixate on purity specifically: free of fat, low in calories, fitting a particular and narrow set of criteria that prioritise thinness and the appearance of discipline above health. In this consumer capitalist logic, the ultra-thin body is equated with hard work, efficiency, and moral goodness, while other bodies are aligned with laziness and inadequacy. Clean eating is prescriptive, admitting only those who look the part, and profiting from those who see ‘clean’ foods as a way to gain access to cultural capital. The real giveaway that clean eating is more about the state of your soul than getting your five-a-day is the illusion of a lack of effort that is a crucial part of the message behind the image. The most successful clean eating Instagrams are a study of moral perfection in 1080px by 1080px squares. The narrative of this carefully curated portrait of the ideal woman is that she never struggles with temptation – she faithfully adheres, and is rewarded with moral validation.

The Milkmaid, Johannes Vermeer, c. 1657–1658

3. Recently, a shift in public opinion has taken place. Even Deliciously Ella herself, the glossy-haired patron saint of wellness blogging, has recognised it and renounced the term ‘clean’. Writers confronting the damaging effects of wellness culture reject the idea of food as an image rather than an experience, focusing instead on the pleasure of eating extravagantly. Recognising that there is no reason to feel guilty for eating is a crucial step in rewriting our cultural relationship with food. But exchanging a culture of restriction for one of hedonism is not the solution.

Ordinary, ‘unglamorous’ food often has the greatest power to heal, if not in the transformative sense that wellness culture suggests. When I was eight, I went to my best friend’s house on Friday afternoons. We’d sit at a little two-seater table in her living room and listen to Harry Potter audiobooks while eating frozen pizza with a glass of UHT milk. It wasn’t sophisticated, but as a child it always felt special and comforting. The meal that Vermeer’s Milkmaid is putting together isn’t elaborate, but a profound sense of calmness emanates from the painting. She’s doing something simple that she’s done a thousand times before and will do a thousand times in the future. It’s a quiet moment in a busy week – a moment to shrug off the day like a rain-soaked coat and notice what the light’s doing. It’s in this way that cooking and eating can be an act of meditative self-care. The sugary hedonism of a Cadbury Twirl is one type of pleasure, but there’s a quieter one to be found too. Doing something kind for yourself, even, and especially, with ordinary ingredients and methods, is its own type of emotional healing.

Sunflowers, Vincent van Gogh, c. 1888-9

4. The first time I saw Van Gogh’s sunflowers, I wanted to eat them. The way they glowed was mesmerising, the only way to describe the colours delicious. There’s something in the brushstrokes that’s distinctly edible. I think this impulse comes from wanting to get closer to the moment preserved by the painting, to the feeling that the artist felt. In some ways that’s what painting is – a perfectly contained moment, like a cake under a glass dome. Food as portrayed in art is often about status, but there’s another connection between the two that is often overlooked – the similarity between the sensory experiences of eating something delicious and seeing something beautiful.

For me, lemons are the ingredient that have always cut through the oppressive heat of the lowest points in life. Once, in a therapy session when I should have been thinking about myself, the idea of lemons appeared fully formed in my head and wouldn’t leave. I couldn’t stop thinking about their burning, sun-like scent, the bright yellow of their dimpled skin, their stained-glass segments when cut open. I bought a bag of them, the biggest and most beautiful I could find, on the way home. They made me feel alive. I spent most of the next week drawing them badly, trying to capture what it was about them that felt like light.

Those lemons were objects of art then, but that was just as true when I finally used them, in salad dressings and pasta sauces and on the edges of drinks. Food looks beautiful in a still life painting, but it’s more beautiful and more substantial when you can taste it. The lemons marked the start of my appreciation of food on an aesthetic and artistic level, and of cooking as a kind of therapy for me.

The use of food as a status symbol, both in art and in wellness culture, has damaged our cultural relationship to eating. But this doesn’t mean that an aesthetic appreciation of food always has to be this way. Cezanne got it – those burning, shifting patches of colour in his still lifes, the desperation to capture the colour just as it lay on the surface of the fruit. Artists have been attracted to food because of what it can say about culture, seeing its artistic potential in its potential symbolism, of luxury or gluttony, sexuality or revulsion. The idea of food as an art object isn’t compromised forever – we can reclaim it, and our cultural relationship to eating, by appreciating its aesthetic qualities. Seeing the sensory experience of eating as an artistic one can transform it into a celebration of the everyday miracle of being alive.∎

Words by Imogen Whiteley. Art by Sasha LaCômbe.