Farewell to the EFL

the people are all homesick today or desperately sleeping,

Trying to remember how those rectangular shapes

Became so extraneous and so near

To create a foreground of quiet knowledge

In which youth had grown old

— John Ashbery, ‘The Bungalows’

Oxford has enough limestone. Tourists and traditionalists like it—students-turned-influencers would be nothing without it—but the honeyed surfaces of the city centre can get a little sickly, especially with a deadline looming. The English Faculty had always been, to me, a blessed relief.

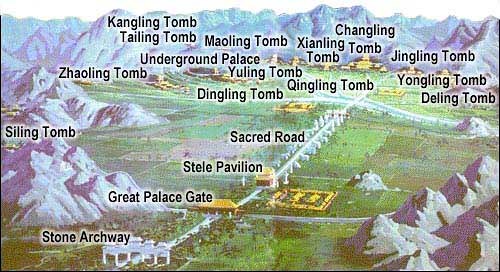

Over the long vac, English has left its old home behind. For a while, though, nestled between Uni Parks and Holywell Street, the buff brick of the St Cross Building has been kept at arm’s length from the sandy cohesion in the middle of town. The English Faculty Library was established in 1914, but only conceptually: before finding a spot in St Cross, the collection bounced around Oxford, sofa surfing in other faculties. By the time building plans were being drawn up, its shelves were so stuffed that it was considered a health hazard. But it was about to be the sixties, so something had to give. Set safely apart from the Rad Cam and its satellites, the St Cross site allowed architects Leslie Martin and Colin St John Wilson to think along the lines of modernism for the faculties of English and Law.

The St Cross Building is not the best-loved in Oxford; most would put it somewhere between an eyesore and a bore. Lots of us, including myself, are at best agnostic to most sixties architecture. It’s still in that awkward stage after the radical thrill has worn off, but before nostalgia fully sets in. Le Corbusier was all the rage at the time, so of course Oxford’s new building had to be a machine—a network—a system: when I hear this I can’t help but picture pistons and girders and levers. It doesn’t feel intuitively literary, though perhaps that’s my lack of imagination.

Anyhow, the English and Law building isn’t mechanical. It’s made up of a series of interlocking boxes, but they’re broad and unhurried. Geoffrey Tyack wrote that the outer staircase, in its impressive scale, evoked ‘subliminal images of the Odessa steps in Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin.’ It’s an unfortunate comparison, and not one I’ve ever been struck with myself. Perhaps the odd exhausted finalist, though, on their way into a Troilus and Criseyde revision lecture, has quietly likened themselves to a brutally massacred civilian. After climbing the outer steps, you descend again into the belly of the building, where the lecture rooms are sunken and windowless. Inside the wood panelling is abundant and richly stained. It’s hot, and all that dark wood can start to feel oppressive after an hour sitting shoulder to shoulder with your coursemates.

The English Faculty Library—at last a real, physical space—stands in bright contrast to the rooms below. It’s white-walled and open, with generous avenues between the shelves; these make the most of the light from the strip windows which wrap around the building. The ceiling is all skylight. The senior librarians, Helen and Jo, told me they’d miss the light in the library after the move—after all, it’s not the first thing you’d associate with working amongst the stacks of the Bodleian. Jo said wistfully that she’d miss the sound of rain on the roof. The sunlight, the rain: the EFL is full of little intrusions from the outside world, which is all too rare for the armoured interiors of Oxford University.

I quickly became fond of the EFL in my first year. I liked how it wasn’t a destination library; its total lack of glamour meant there would always be a seat. (The seats, by the way, like all the furnishings, are sixties originals, and there’s a whisper of the egg chair in their ergonomic shape.) I liked arriving there in the morning, always forty minutes or so later than I had planned to. Coming from Keble, I fell into the rhythm of taking the picturesque route through Uni Parks. I loved that little walk, and having a reason to do it. I used to treat myself to a browse of the twentieth-century poetry section; I’d select the most beautiful edition of John Ashbery (the Carcanet Press hardback of As We Know, if you’re interested), or some other poet too clever for me, and lay it proudly on my desk in my room, unread. I just liked looking at it. The EFL, more than anywhere else, has taught me how to judge a book by its cover. Many times I have refused to borrow the only available copy of a set text because it was simply too hideous. In my experience, having so many editions of the same canonical works at one’s fingertips sharpens the aesthetic senses far more than the scholarly ones.

The building’s own exterior doesn’t stand up to such superficiality, so easily outshone by the crenelations and gargoyles which crowd the rest of the city. But it has a solid, homely charm—you know the St Cross Building. Your local council probably operates out of something similar. And perhaps there’s something to the structure which suits the work going on inside: Martin and Wilson subscribed to the Corbusian motto that the Plan is the generator, that ‘without a plan, you have a lack of order and willfulness.’ Generations of undergrads have come to accept this same hard-learned lesson within the EFL’s walls, scrambling to make a tutorial essay out of a few bullet points and a couple of hours.

I don’t believe I’m the only one with an attachment to the St Cross English Faculty, but there hasn’t been a huge outcry against the move to Jericho. And I don’t want to over-elegise; the St Cross Building isn’t going anywhere, after all. Now that Michaelmas has begun, my fellow sentimental EFL readers and I will be herded into the Stephen A. Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities, under showy archways emblazoned with the name of a man with a strong claim to being the world’s biggest slumlord. (Schwarzman is CEO of Blackstone, the largest asset management company on the planet, involved in everything you might expect from a company worth over $1tn.) It’s spectacular, historic, state-of-the-art; it has libraries, exhibition spaces, a concert hall, and a recording studio. It’s made of limestone.

I’m always uneasy with change, but there’s something especially poignant about the loss of the EFL at St Cross to the shiny new monolith of the Schwarzman. 60 years in a building isn’t a long time in Oxford; I wish people were sadder about it. Those rectangular shapes will soon become extraneous, at least to English students, and I’m sure I’ll feel a little homesick.

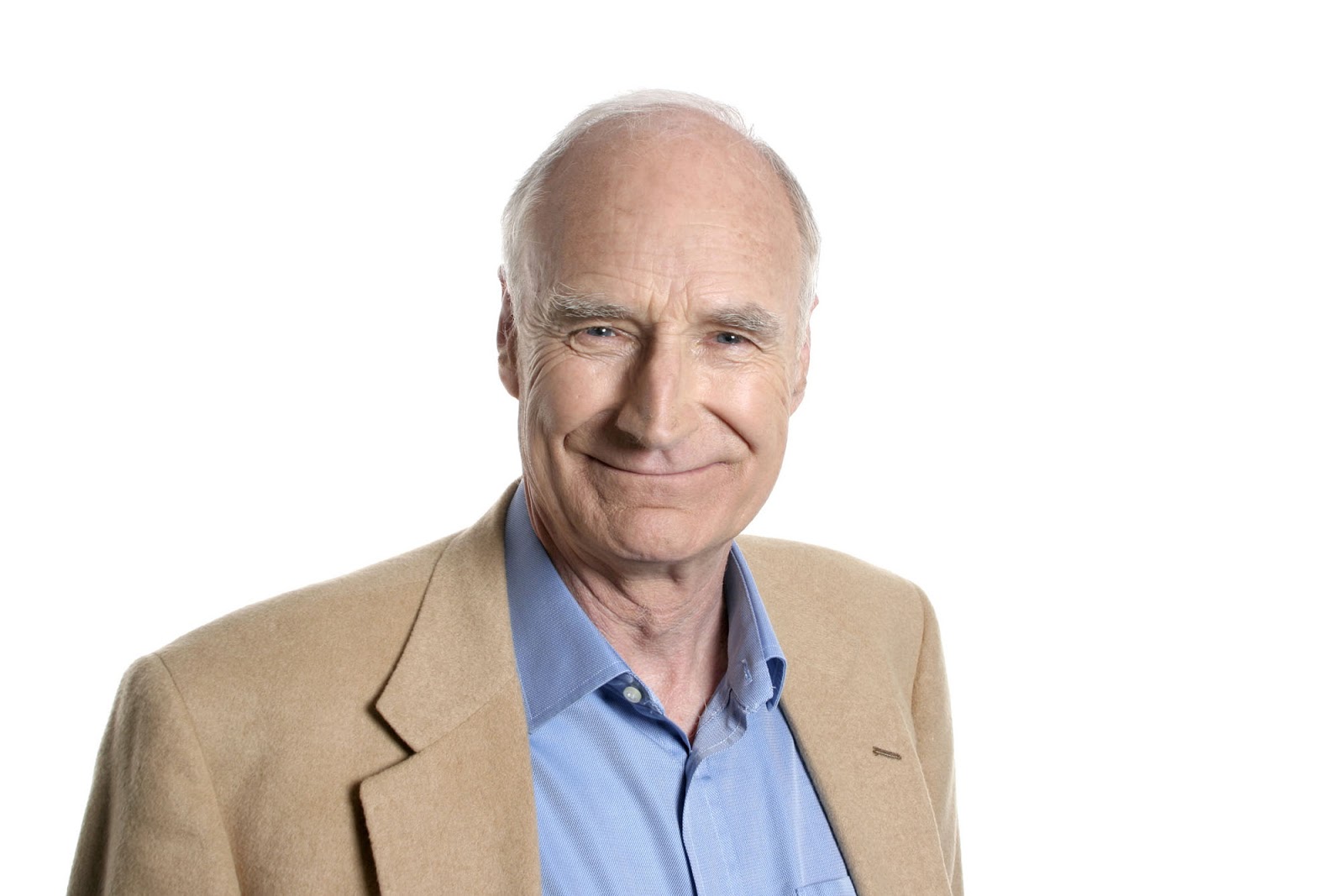

Words by Isobel Brewer. Image by Timothy Endicott via Wikimedia Commons.