CRITICAL NOTICES: The Tempest, Bull, Suddenly Last Summer, Troilus and Cressida

The Tempest (Magdalen President’s Garden, 20th-24th May)

The Tempest lends itself particularly well to a natural setting, and the walled garden at Magdalen provided an apt location for a production fascinated by control. When I took my seat, the glowing loops of LEDs and wiry backdrop of microphones amongst the shrubbery didn’t quite give me the ‘remote island’ setting that I expected. However, it was soon clear that sound and light would be central to the production: magic, expressed in song and soundscape form, became less of a theatrical spectacle and more of a study in deception, manipulation and disorientation.

Clearly taking ‘the isle is full of noises/ sounds and sweet airs’ very literally, directors Seb Carrington and Aidan Lazarou, alongside sound designer Lucian Ng, fully pad out Shakespeare’s musical interludes. From the roaring storm to eerie songs sung by Ariel (EP Siegel), Prospero’s (Artemis Betts) power is immediately sensory—and also stolen. Betts’ Prospero very clearly depends upon her magical servants for any real potency. Ariel and Caliban (Henry Nurse) deliver standout performances as the magician’s mistreated slaves, forced into servitude by emotional manipulation and threats of violence. I found it increasingly difficult to sympathise with Prospero, though she appeared on the verge of breakdown herself; relationships are solely on her terms, even with her own daughter.

I loved Liberty Mountain’s costuming—my first scribbled note was ‘Excellent cape!’. In harmony with the lighting, Prospero and Ariel’s blue garments contrast with the reds of Caliban, Trinculo and Stephano, whilst the nobles are clothed in greens and browns, the distinctions of courtly hierarchy also visible. Lighting changes during scenes of conflict mirror power transfer between the groups via their corresponding colours, a clever technique that only became visible in the darkness of the second act.

Whilst I thoroughly enjoyed the relationship between Prospero and Ariel, and Caliban and his new masters, I felt less convinced by that between Ferdinand and Miranda (Toby Bowes Lyon and Annabelle Higgins). Though their love story is engineered, the discrepancy between their meeting and their betrothal—the leap from Miranda enchanted by Ferdinand’s manliness, to Prospero dragging her daughter’s hand into the arrangement—felt too jarring of a change opposed to the developed and nuanced relationships elsewhere. The omission of the disappearing banquet and the wedding masque scenes was prudent, given the difficulty in staging and the length of the play, but Ferdinand’s brief reaction to invisible spirits felt out of place amongst the forceful songs.

That being said, any chance of happy union/reunion in the play was quashed deliberately, leaving the resolution full of underlying tensions as the pace slowed down, pauses between lines lengthened, and a sense of collapse abounded. The electric static soundscape left the scene feeling unsettled; perhaps a reminder that this happy ending was entirely artificial. Maybe it would have been nice to have some lightness, but the desired impression was certainly made, and certainly not one I expected from another garden Shakespeare. ∎

—Eve Wilsmore

Bull (Burton Taylor Studio, 20th-24th May)

What makes theatre so great is that you can’t leave when it gets uncomfortable. Mike Bartlett’s acid-tongued 2013 play, ‘Bull’, is all-too aware of this fact. It forces its audience to sit through 55 minutes of some of the worst things we can possibly do to each other.

On the surface, it’s a comment on the venom of modern capitalist life. Three young employees wait to see which one will be fired by their boss by the end of the play. Two take great lengths to torment the weaker one—ousting him for their own materialistic, self-obsessed gains.

It’s much more than social politics, though. Instead, the stakes are made much higher by Bartlett’s visceral and rhythmic writing. It’s about survival. How we can act if given the opportunity. As the play makes it clear, we are no better than animals in how we treat each other.

There are some great moments where the direction and acting shines to allow this intense, animalistic cruelty to come across. For example, Leo Bevan’s Tony (a stand-out performance among a strong cast!) stands proud, centre-stage, and demands his colleague, Thomas (Aidan Kane), to place his face on his exposed chest. It’s an obvious social game—made more chilling by the unflinching stillness of Bevan contrasted with the skittish pacing of his weaker co-worker.

The scene’s elongated to excruciatingly gripping lengths as Thomas tries to worm his way out of the playground bullying from those around him. It ends with a particularly striking image: Selma Lee’s glacially impervious Isobel facing the audience, with a peacock-proud grin, rubbing her face on Tony’s chest. As a consequence, it becomes such a successful moment for the actors involved, as well as director Charlie Lewis.

Yet, I don’t think the stakes of absolute survival, at all costs, are fully realised in Cross Keys/Boulevard Productions’ adaptation.

Firstly, in order to make the truly explosive moments of the play work, there needs to be some sort of build up to them. True electricity on the stage comes from knowing how to make the tiny moments—the suit Thomas wears; the dandruff on his hair—catastrophic enough to destroy a person.

The play starts with a great and compelling intensity, but it doesn’t change substantially enough. And it has little scope to go any further as a result. The entrance of their boss, Carter (Cameron Spruce), provides a great opportunity in the script to inject some new energy into the play, but it is underutilised. Intensity, when sustained too long without changing, only leads to a slight sense of burnout.

In conclusion, ‘Bull’ is a play that shows characters hate each other—and these characters are so evil that it makes you hate yourself a bit as well. There’s absolutely nothing to redeem Isobel and Tony as they destroy their fellow co-worker with quasi-Machiavellian creativity. What happens to Thomas is frighteningly unfair.

If Cross Keys and Boulevard Productions are going to stage such a confrontational play, then it needs to believe in this message ever-so-slightly more. Give us proper evil. Make us wait for it. Make us suffer.∎

—Ruby Tipple

Suddenly Last Summer (Burton Taylor Studio, 20th-24th May)

It is possibly the most Freudian theatre experience in Oxford—watching your college mother playing a mother, in a play sort of about incest, with a psychologist on stage. Suddenly Last Summer is not your A Streetcar Named Desire. It is a minor work that encompasses everything that makes a Tennessee Williams. It is sort of hyper in every sense. In short—it is his B Movie, best taken as a kind of self-conscious melodrama. And the Analogia Productions staging is even more John Waters.

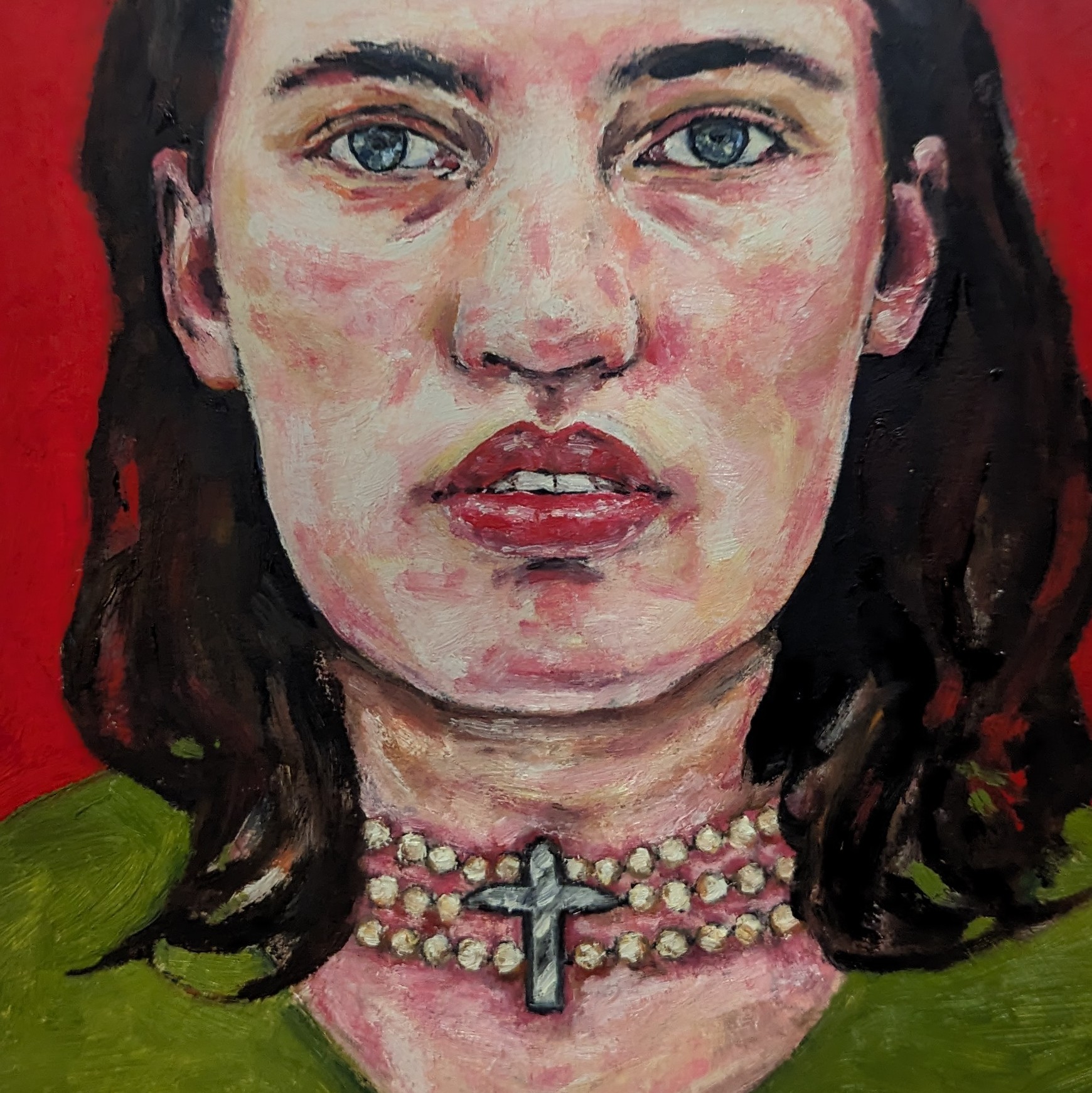

Set against a red mural of Pollock x Bacon—completed in one of the quieter nights of a Peckwater living room (as seen in Jem Hunter’s story, who plays Dr Sugar)—sometimes Sebastian’s luscious New Orleans garden, and other times the sublime landscape of his death on the Galapagos: this is a Southern Gothic of Pink Flamingos.

This 1959 play surprisingly taps into hot topics: lobotomy, cannibalism, dandy and diva, mother! Céline Denis’ neurotic mother is reminiscent of Victoria Ratliff in White Lotus—’Piper no!’ The impatient brother played by Akarsh Shankar could also fit into the new season. Hafeja Khanam who plays the institutionalised Catherine delivered an impressive monologue.

The marketing seems to be aware of—and has capitalised on—the play’s relevancy, by which I mean the marketing is really good, like, better than most: a moodboard of Blake and Bosch and Pasolini’s Salò; moody headshots by Louisianian waters (probably just Worcester lake). It almost makes you forget it is a BT play.

There were interesting uses of one of my less preferred venues in Oxford—I would let you see for yourself. Michelle Tse does the sound again (Is there a show in Oxford she is not in? Amazing woman). But remember that if you do go to BT, it might be just as hot inside as the semi-tropical setting, so opt for a jacket not a jumper.∎

—Zac Yang

Troilus and Cressida (Burton Taylor Studio, 13th-17th May)

Despite being set against the backdrop of the Trojan War, the tensions of Moribayassa Productions’ staging of Troilus and Cressida came not from the under-emphasised central conflict, but from a wide array of conflicting theatrical choices.

Disorienting decisions were made across design and direction, in many instances with ample overlap between the two. Between lines (which, due to the original actor dropping out weeks before, were read off an iPad), Pandarus—covered in white face paint—could be seen ripping a Juul, blowing massive clouds between teeth smeared with black paint. And while other actors maintained their natural accents, Cressida’s servant, Alexander, had an inexplicable American Southern drawl, and Diomedes had a similarly rogue Russian accent.

While the play’s primary visual component—a VHS-style early ‘00s TV that occasionally played pre-recorded scenes—was aesthetically compelling, it served no narrative purpose whatsoever. Its Y2K look also proved somewhat discordant against the mix of costuming which stylistically ranged from Berghain-reject, steampunk prom date, junior college vice principal, and Depop balaclava knitter.

However, the eponymous leads of Troilus (Rufus Shutter), and Cressida (Georgie Cotes), deftly delivered incredibly strong performances. There were also memorable punctuations by more minor characters such as the mischievous Thersites, phenomenally acted by Walter McCabe, and Ulysses (Gabriel da Silva). Unfortunately, these actors’ evident talent simply struck another contrast against the more two-dimensional performances of the remaining cast.

On the whole, perhaps we can sympathize with Troilus: it can be frustrating when someone can’t commit.∎

—Mary Lawrence Ware