In the Path of a Distant Star: in search of Allende’s lost generation

by Nicholas Clark | March 23, 2022

In late December 2021, following a long nail-biting campaign, insurgent left-wing candidate Gabriel Boric was announced as the victor in Chile’s presidential election. Boric, a former student leader, swept the polls roundly defeating far-right candidate José Antonio Kast, becoming the youngest president in Chilean history. After decades of far-right dictatorship and neoliberal governance, the election represented a turning point in Chile’s recent history, reflecting the aspirations and hopes of Chile’s young dreamers. The clash between Kast and Boric naturally opened up old wounds. Playwright Ariel Dorfman wrote that the election was for the “soul of Chile”, one inevitably moved and shaped by “ghosts”, namely Chile’s dead. With Boric’s victory, many now feel that they can look away from the past and begin to look to the future.

The election followed significant calls for dramatic structural reforms in Chile. In response to high rates of social inequality, protestors had taken to the streets in 2019 to demand sweeping and radical constitutional changes. Boric himself played a significant part in negotiations over the country’s constitutional redraft and his election is indicative of the rising tide of popular discontent in a country scarred by its recent past. The ascent of Chile’s left is a rare glimpse of hope for reformists and revolutionaries, Boric being the first left-wing president since the end of the far-right military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. This comes at an age where, in the words of Frederic Jameson, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”. To break out of this paradigm requires hope in large-scale political alternatives during a period in history where this has seemed almost impossible. Chile, perhaps, has shone a light on the path forward for social movements.

Chile has a tumultuous political history. The country’s old constitution, now discarded following a 2020 plebiscite for constitutional reform, was drafted under Pinochet’s dictatorial leadership. As a right-wing military official, Pinochet seized power in September 1973, rapidly leading to a consolidation of his position through far-reaching reforms which decisively broke away from the socialist government of Salvador Allende. Prominent within his new government were the interventions of the ‘Chicago Boys’, a group of University of Chicago faculty members which included the economist Milton Friedman. These advisors advocated for substantial economic reforms such as the marketisation of the Chilean economy, stripping state-held assets through privatisation, and dramatically cutting social spending. These reforms were the basis for the ‘neoliberal turn’ which quickly inspired other movements elsewhere, galvanising Chilean economic growth and making the country one of the wealthiest in Latin America. This, however, came at the substantial cost of vastly exacerbated inequalities, political illiberalism until Pinochet’s abdication from power, and the execution or internment of tens of thousands of political dissidents.

Chile’s lost generation can be glimpsed through the eyes of its politically and literarily fervent poets, artists, and thinkers, who came of age in the age under Allende, only to be exiled (as was Bolaño), killed (as was ‘Chile’s Bob Dylan’, Victor Jarra), or to join the ranks of the country’s desaparecidos (disappeared). Chile’s writers – Pablo Neruda, Isabelle Allende, Gabriela Mistral, to name a few – have escaped the boundaries of language and translation. The late author Roberto Bolaño, described as the “sad Socialist son of Pinochet’s Chile”, was renowned for breaking the perception of Latin American literature out of the confines of genres like magic realism, in turn gifting us with a useful set of metaphors for understanding the feelings of hope, desire, and distance of Chile’s lost years.

Bolaño’s posthumous work has attracted significant attention in the Anglophone literary press. An early novel of his, Distant Star, captures the anguish and political hopelessness of the Pinochet years. Written from the hazy perspective of an exile, Arturo B – a plain allusion to the writer himself – the novel revolves around his acquaintance with poet Ruiz-Tagle (who is really, as it is revealed, Carlos Weider). Following Pinochet’s assent, Arturo’s capture, and subsequent imprisonment, his acquaintance later turns out to be a far-right air-force lieutenant. Weider, whose presence haunts the novel, skywrites poetry in a WWII-era Messerschmitt plane over the Andes. Many years later, in exile in Spain, Arturo finds a now exiled Weider, meditating on the passage of time, and the recession of the Pinochet years from popular memory. Arturo exclaims “Chile had forgotten us as well”. For Chile’s exiles, the ‘distant star’ also stands for a country now far away in both space and time. As Arturo is interned at Santiago’s Estadio Nacional, along with thousands of other political prisoners, Weider writes “death” in the sky above the stadium. Weider encapsulates the bitter irony of his own freedom-indulging in poetry, far above Santiago, unmoored by the horror of the ground, a ‘distant star’ that dualistically represents freedom and oppression.

Allende’s government is a particularly fascinating aberration in the polarised politics of the Cold War, a rare, socialist third way between the free-market capitalist West and the Marxist-Leninist model of the Eastern bloc. Allende, with the backing of his socialist party, favoured a constitutional transition to a democratically owned model of ownership and production. His policies featured some hallmarks of post-war social democratic governance, including the nationalisation of key industry and a move to socialistic ownership, greater than any other democratic governments had attempted. Key to this agenda was “Project CyberSyn”, a cybernetic model of production that paired nascent computing technology with central planning, networking hundreds of Chilean factories. Plans to expand this network were rapidly halted by Pinochet’s assent, with the main operations centre destroyed soon after. Bolaño writes that the revolutionary fervour of the Allende years presaged what was to follow, as young members of the Chilean literati dreamed of “revolution and the armed struggle that would usher in a new life and a new era”. Before its swift and brutal demise in 1973, the people of Allende’s Chile caught glimpses of a new sort of society, brutally stopped in its opening phases.

Pinochet’s rule, too, witnessed the birth of what is now described as neoliberalism, a model quickly adopted by western democratic governments in the following decades. Indeed, the assumption of neoliberalism as the ‘final stage’ of Western development, with no horizon for large-scale change or development, has become formative to our understanding of politics. Neoliberalism itself has been described as post-historical, a miasma that binds the future and the possibilities contained within. Margaret Thatcher claimed, brusquely, that “there is no alternative”, referring to the foreclosure of political possibility that came with the assent of neoliberal capitalism. As history ostensibly reached a terminal point with neoliberalism, however, little thought was spared for the bodies it left in its wake.

Arturo’s exile in Spain, a refugee from Allende’s deceased political dream, is an effective metaphor for the position of the political left in the neoliberal era, broadly outcast from mass politics and unable to envision an alternative to modern capitalism. Pinochet’s political programme provided the ideological mettle for similar market reforms in the US and UK, adopted elsewhere in the West and the developing world. These too saw many more such casualties of hope, from the miners crippled by Thatcher to the victims of Reagan’s interventions in Central America. Dissidents who opposed the expansion of market reforms found little political refuge, as traditionally left-leaning opposition parties in the West embraced marketisation, with ‘third-way’ politics quickly becoming the platform of the centre-left. Despite the brutality of much of the former Soviet Union’s socialist model, the shock of market reforms in the 1990s was similarly apocalyptic. For the children of neoliberalism, caught between the dreams of the past and an inevitable, inescapable future, aspirations for reform and liberalisation quickly gave way to destitution and political decline. For disappointed revolutionaries, such as Bolaño, the absence of a political future left only the outlet of fiction, writing “nobody, and literature even less, is capable of not blinking for a long time”.

To the relief of many international observers (not to mention Santiago’s moderates), Boric’s recently announced cabinet adheres closely to a social-democratic agenda, emphasising a green recovery from Covid-19 and substantial increases in taxation and welfare spending. In many countries seeking to rebound from the pandemic, this is less a task of revolutionary politics and more of a new economic orthodoxy. Indeed, the label ‘social democrat’ is one that Boric has openly embraced, a break from more overtly radical political predecessors in the Latin American left. Allende’s visionary social thinking has not translated to the modest political agenda of the new Chilean government, to the disappointment of Chile’s past and present radicals. But for a left-wing that has only recently regained confidence in its vision of another world, his election nevertheless represents a turning point. Democracy in the twenty-first century is caught between a feeling of inescapability, and hope for an exit. However small it may be, Boric’s victory may coronate an off-ramp from the inevitable.

Dreaming is often compromised by the difficult task of governance. Boric’s government may find this too, as the heady optimism of electoral victory gives way to the arduousness of compromise and legislation. As Allende’s ultimately failed struggle proves, the task of building “Heaven on Earth” is long and treacherous and such a lofty aim may very well find itself to be fruitless. Indeed, more pessimistically, Bolaño writes of the young Chilean left as “vaguely aware that dreams often turn into nightmares”. Boric’s ascension, nevertheless, is a reminder that struggle, both small and large, against the seemingly hopeless and totalising weight of injustice can reap rewards. Allende, in his last speech hours before his death, rousingly announced: “I have faith in Chile and its destiny. Other men will overcome this dark and bitter moment when treason seeks to prevail”. Regardless of one’s politics, ambitions, or credence to romanticism, change may have been found after decades of wishing on the flicker of a distant star. ∎

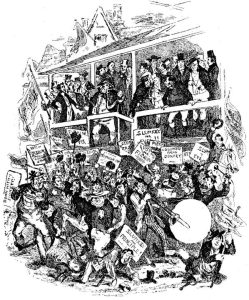

Words by Nicholas Clark. Art by Eloise Cooke.