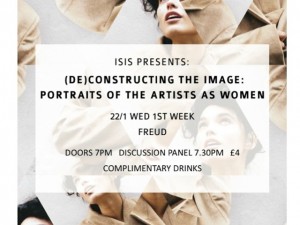

Pearl Necklaces, ‘Dada’ Bracelets and Crucifixes: Jewellery and Image-making

by Layla El Hajame | January 22, 2024

In the intricate realm of crafting one’s image, be it in the political or personal spheres, the choice of jewellery serves as a nuanced yet impactful form of self-expression.

Whether it’s the enduring charm of pearls, favoured by iconic women like Jackie Kennedy and Lady Churchill, or the seemingly unassuming bracelet on the hand of Rishi Sunak during his political ascent, these adornments take on a meaning beyond the aesthetic. In the age of social media, a single image can spark a cascade of opinions. Consequently, individuals in the public eye have increasingly invested careful thought into their jewellery (among of course a myriad of other) choices.

Historically, jewellery has long stood as a powerful communicator. It has always transcended mere adornment, conveying status, symbolising allegiance, religious belief, and cultural belonging. From the social standing suggested by ancient Egyptian headdresses; to the language of remembrance, dedication and sorrow expressed by Victorian mourning jewellery; to the sacrifice, valour and pride emanating from war medallions – the communicative power of jewellery has been immense.

Some other choices have been much more subtle, but no less meaningful. Take the tradition of women in politics donning pearl necklaces, for instance. In the words of Jackie Kennedy: “pearls are always appropriate”. Lady Churchill went even further, naming pearls her “security blanket”. To these women, something about pearls seems to strike a perfect balance. They evoke an elegance and poise that is tempered simultaneously by just the right amount of approachability. In their eyes, the relative attainability of pearls in comparison to say, diamonds, set them apart as the ‘appropriate’ choice.

If Harry Winston was correct in declaring that “the love of showing off diamonds is human nature”, then Churchill and Kennedy (who both owned their fair share of diamonds) certainly made efforts to suppress this primal need when on political engagements. The jewellery of these women served as statements as to which facets of their identities they choose to emphasize in specific contexts. The pearl necklace in the political sphere was (and indeed is – take for instance, Kamala Harris) inextricable from a wider project of balancing the delicate equilibrium between power and relatability in politics.

This notion of relatability, though quite specifically sans the grace of elegance, surfaces elsewhere – namely, on the hand of none other than Rishi Sunak. During the peak of his bid for leadership in the Conservative Party, Sunak regularly sported an untidy, rather wholesome, bracelet adorned with beads that spelled ‘dada’. Crafted by his young child, the messiness and casualness of this bracelet no doubt softened his image.

While Sunak’s bracelet, simply yet admirably, embraces personal and familial connections, it is difficult to not notice something of a tension between this and the experiences of women navigating a path that demands proving commitment to their political careers. This no doubt often involves a distancing, at least in professional contexts, from personal connections and maternal responsibilities that may be perceived as conflicting with the expectations placed on them.

Admittedly, this is a somewhat strange comparison to draw. I do not seek to take the example of a few women wearing pearls, and a singular man wearing a messy bracelet to make the argument that jewellery choices in the political sphere reflect gendered privileges at all times. Yet I do think that there is something to be said about the way jewellery can be used to communicate a point. Indeed, the point one seeks to prove, whether that be a commitment to the professional or the sentimental, can certainly in these cases be read along gendered lines.

It is certainly evident that different political figures have used jewellery to prove something unique about their identity and priorities, but this does not render every bracelet or necklace on the hand or neck of a politician a political tool.

In seeking to distinguish myself from that GCSE English Lit teacher who sees, behind every singular word on the page, a deep intentionality on the part of the author, I must add that some jewellery is quite possibly, just jewellery.

I would imagine after all that politicians, like the rest of us, are most probably capable of simply fancying a particular piece because it looks rather nice, or has some sort of sentimental value. As a Muslim with an embarrassingly large collection of rosary and crucifix necklaces, I can attest that personal jewellery choices aren’t always a direct and intentional reflection of self. When I throw on a crucifix half-asleep ahead of a 9am lecture, I do so quite simply because it looks rather pretty. The last thing on my mind is the image I wish to portray to the world.

Yet, nonetheless, it sparks introspection. Might it be the case that in wearing such necklaces, I am addressing a subconscious desire to connect with the Christian side of my family? I do think it entirely possible that a yearning to bridge the religious and cultural gaps within my own heritage has led me to such jewellery choices. It seems to me that there can be something deeply exploratory about wearing jewellery. It serves as much as a vessel for the confused, unformed and forming identity as it does the meticulously curated one.

So, what, then, does jewellery truly say about the wearer?

I would argue that, as with any art form, the beauty of jewellery lies as much in its ambiguity as its capacity for directness. It embodies and melds together the unspoken, the evolving, and the carefully crafted facets of our identity. And, even if you cannot unearth some profound meaning in your own jewellery collection, there remains something notably personal and somewhat nurturing in the ritualized act of adorning oneself with these pieces. And, if all else fails, and my musings prove vacuous to you, there is an undeniable solace in this simple truth – they do look lovely.∎

Words by Layla El Hajame. Image provided by Wikimedia Commons.