Voices from the Aral Sea: Oxford Students Take On Oral History

Over the summer, three students from St Hugh’s College – James Chapman, Annie Liddell and Oscar Fraser Turner – will be recording an oral history documentary about the Aral Sea crisis, an environmental disaster currently unfolding in Uzbekistan. At first glance, oral history might seem an odd approach to take. The response to environmental crisis – especially one on this scale, where an entire sea has shrunk to a tenth of its original size – is typically scientific research. But while the situation of a student filmmaking expedition to Uzbekistan might be somewhat unprecedented, the team are keen to point out the various precedents which inspire and justify their methods.

When I ask second-year history student Oscar about oral history, he responds in the tone of someone name-dropping a favourite celebrity: “Have you heard of Svetlana Alexievich?”. Alexievich, author of the ground-breaking history Voices from Chernobyl, sent oral history to new heights of fame when she was awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature for what the judges called “polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.”

The Nobel committee acknowledged what practitioners of the approach already know: that oral history is uniquely able to capture the immediacy and emotional rawness of speech. In the title of Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl, it is voices which stand in for the people from Chernobyl. Her study, like the oral history itself, implies that the ability to communicate is what it means to be human. Even in commonplace idioms, finding one’s voice is a metaphor about finding the ability, or perhaps the courage, to begin storytelling.

Alexievich describes oral history as “the spilling of these feelings past the facts”. It’s an approach to history that sees truth as fact combined with feeling, with voice as its backbone. Voices, after all, have the power to move: to move the listener, and crucially, to move or travel far beyond Chernobyl itself.

It’s no wonder the Project Amu Darya team are taking such care over voice in their documentary. They plan to translate the final cut into four different languages – Uzbek, Russian, English and Karakalpak, the language spoken in the autonomous region that contains the Aral Sea – and they are currently discussing whether they want a voice actor to read out the translations of their video interviews. Oscar, for one, would prefer the alternative: subtitles and the interviewee’s voice recordings. He points out that dubbing an Uzbek fisherman with the squeaky voice of an Oxford student might introduce some unintended humour to the final product, which they expect to be a tough watch at times.

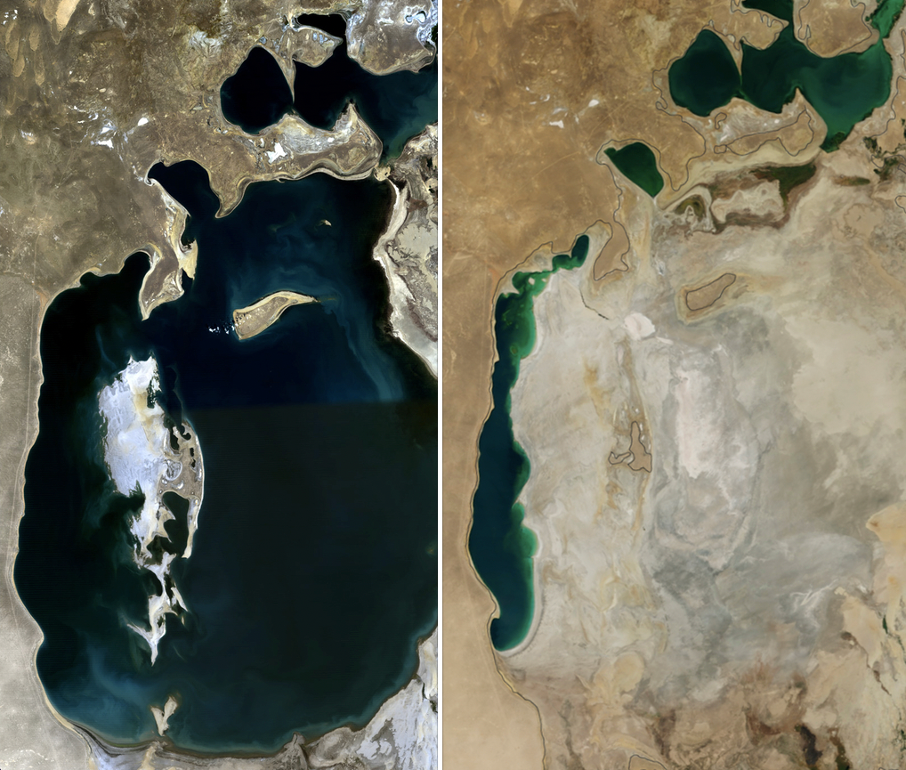

The Aral Sea Crisis is not worlds away from Alexievich’s Chernobyl: it’s another man-made disaster which has permanently altered the natural landscape. This much is clear from satellite and drone photography:

In 1960, the Aral Sea was the fourth largest lake on earth. Subsequent Soviet irrigations projects along the Amu Darya, its main tributary, have led to the decimation of the entire ecosystem. The Aral Sea is now one tenth of its original size, a change that makes this one of the fastest environmental collapses in history.

The human impact of the Aral Sea Crisis, though, remains unclear. The lake is located in an area where there is no access to historical archives, in another striking similarity to Chernobyl. The bulk of the crisis took place under the USSR and under the post-Soviet dictatorship, which continued until 2016. Oscar points out that environmental histories have not been able to include the Aral Sea crisis because of archival restrictions, which is where oral history can intervene: as an approach, oral history distinguishes itself by its use of human sources rather than archives. A sea drying up is, of course, not the same as an explosion at the Chernobyl reactor – it has been happening much more quietly. Oral history, then, could be a response to this silence.

Influenced by Dheeraj Alkolkar, a director who works with oral history, Oscar believes that the narrative arc of the documentary will ultimately come down to decisions made post-production. “It’s research. You can’t impose your own story here, you can only approach with questions. You almost aren’t interviewing your subjects, you’re just hearing them – that’s the goal. Then, after recording, you have to sit with your producer and ask, “What story does this want to tell? Do we want a voice actor to dub it, or are the interviews so unified in their themes that they don’t need it?”

Rosie Robinson, the documentary’s producer, answers my questions from Cannes – unsurprisingly, she is keen to “give the documentary a good run on the festival round”, and has been collating various documentary-specific festivals to enter. Rosie muses, “I’ve heard someone describe the meeting of the academic technique of oral history with documentary as creating a living art form, and I like that a lot. Of course, there are a million different ways of making documentaries, and of telling a story, but the technique of using oral history is one which I’m excited to see at play. If you imagine documentaries we might watch on TV, you might think of an educational voiceover, or talking heads with various experts; with oral history, we’re going straight to the source. The people we’re talking to aren’t experts by virtue of study, but through real, lived experience – there’s no one better to tell the story than them.”

As well as the documentary, the team will produce an academic transcript of the entirety of their interviews, but Oscar stresses that the two products of the expedition serve two very different purposes. The transcript is intended as a contribution to the archives, lending itself to further academic research, whereas the more concise and emotive documentary will be screened for education, public awareness and fundraising, starting with NGOs in Uzbekistan who will use the documentary in environmental workshops at schools.

The educational aspect of the documentary gains an unexpected significance in Uzbekistan, where professional journalists, including a team from the New York Times, have recently been turned away from researching the Aral Sea crisis.

“We really don’t want this to come across as a journalistic project,” argues Oscar. “That’s not something that we think is appropriate in these circumstances. We want this to be educational and that’s helped us with the process of getting visas and getting permission to do the research, because the idea isn’t to critique the potential flaws in the Uzbek management of this crisis. We want to hear the personal rather than the political side of this crisis. And as students, obviously we are less politically motivated than, say, the New York Times, and I think that’s gotten us access.”

“The government’s put a lot of effort into trying to address the Aral Sea crisis now, but since it was so restrictive until 2016, there’s very little conversation about it – it’s quite a slow process to get the environmental awareness ball rolling.” Repression in Uzbekistan seems to have been a key part of why awareness of the crisis is so low: it’s what has prevented a documentary like this being made before, and what makes it so necessary.

Of course, being a student isn’t always an advantage – it remains somewhat baffling that a team with no filmmaking experience are raising upwards of £10,000 to make a documentary. So far, Project Amu Darya is being sponsored by the Oxford University Expedition Council and by the Royal Geographical Society, having attended their annual Explorer conference and won the RGS’s undergraduate fieldwork grant. The team are understandably keen to compensate for the gaps in their own expertise by getting as many experts on board as possible. Oscar adds, “We’re currently emailing a bunch of different advisors, on equipment, on training, on medical, on medical kit on government approval, actually with the Uzbek government on school networks, on, on translator networks, the whole thing. And so the day-to-day right now is basically just building a contact network and working on my photography and video photography skills. I’ve done photography before, but I’ve never filmed anything before.”

“That’s definitely something I’m going to spend a big chunk of the summer working on,” he adds, “hopefully making practice short films and just really getting the technique down. You really need it to be fluid when you’re in the interview – the authenticity of it is so contingent on the fact that you can set up the camera just like that. If it takes 20 minutes for you to get the F stop right on the interviewer, they might freak out and probably won’t tell the same story. You need to enable comfort and enable openness – that comes through.”

The very methodology of the oral history interview – the need for a rapport between interviewer and interviewee – tells a story about a wider need to connect. You might even draw parallels between the network of Uzbek interviewees which the Project Amu Darya team are putting together and the network of collaborators which they have established, drawing on the experience of documentary filmmakers and the Oxford arts scene – collaboration has been integral to every step of the project. In practice, the ‘polyphonic’ quality of the oral history puts a special emphasis on the interactions between multiple voices, lending significance to the ways that they overlap and qualify each other. The documentary aims to build up a rounded impression of a story with multiple sides to it, ultimately leading to an impression of the felt impact of the crisis on a community.

Alexievich begins her Voices from Chernobyl with an extract she calls ‘A Solitary Human Voice’. It’s a story from Lyudmilla Ignatenko, a woman who’d lost her husband after he was sent to put out the fires at the reactor. “They die, but no one’s really asked us. No one’s asked us what we’ve been through. What we saw. No one wants to hear about death. About what scares them. But I was telling you about love. About my love…”

Ultimately, this is what the oral history comes down to. The Amu Darya team are going to Uzbekistan for the living memory of the Aral Sea crisis – not to impose their own narrative, but to be the voices who, finally, ask.

https://www.projectamudarya.org/

@project.amu.darya