Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism

by Eva Stuart | February 7, 2023

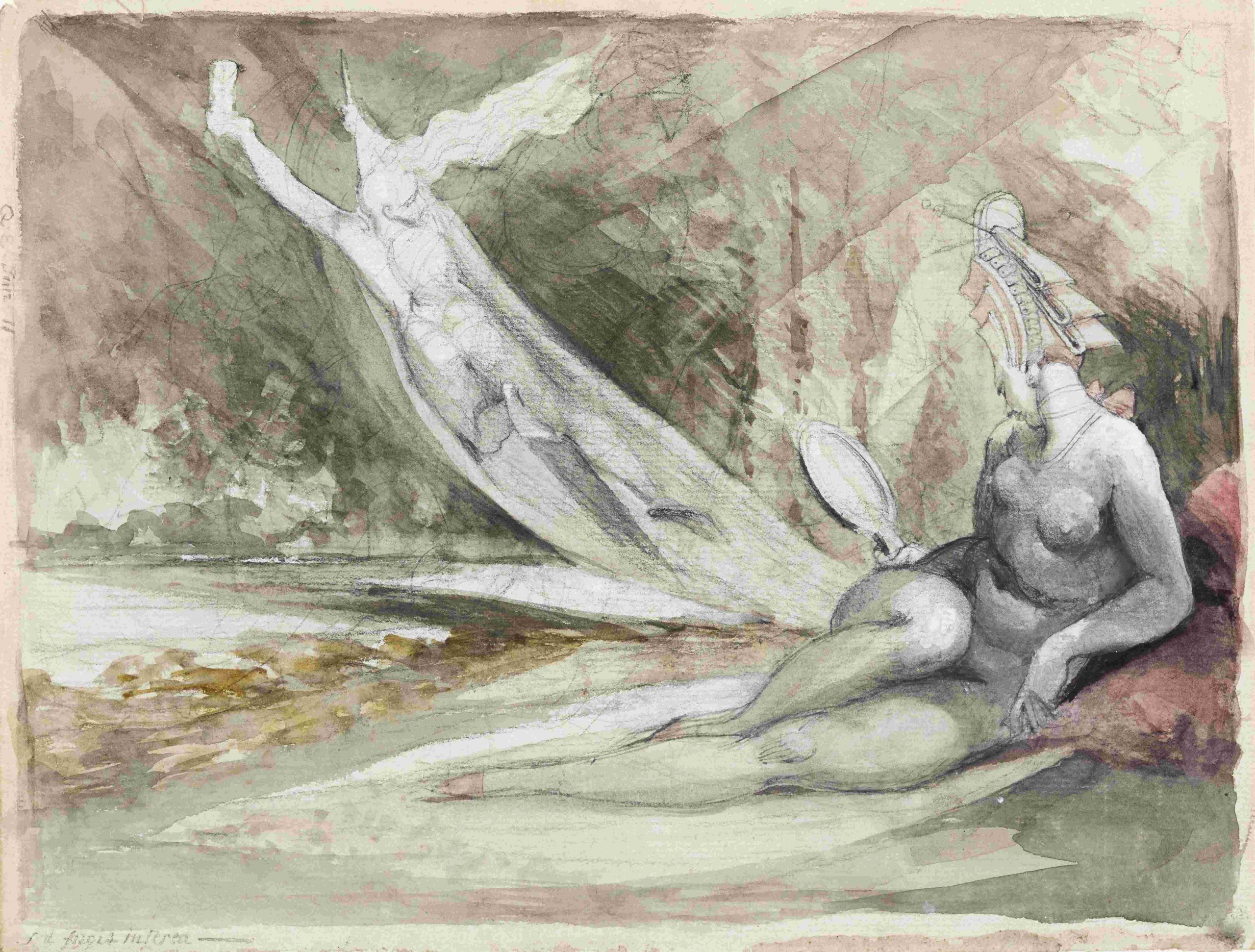

Sophia Fuseli burned her husband’s drawings. Of the tossed sheaves, around fifty were spared and temporarily decorate the walls of the Courtauld Gallery. Each page is a giddy mass of penwork – confident strokes of graphite and washes of pale ink – so that Henry Fuseli’s (1741-1825) sketches invoke a particular allure through their depicted subjects. Courtesans and prostitutes abound, coy yet blatantly conscious of their observer, their postures displaying their figures in luxurious curves. The women possess an unsettling power at odds with the increasingly domesticised, mannerly female of the eighteenth-century societal standard. In one drawing, a woman claws at a man’s hair, forcing his head towards her in a wholly emasculating manner. In another, a courtesan wears a collar and lead. Yet whilst the agency appears to lie with the women, it was Fuseli who contrived the scenarios. These sketches fetishise: woman is portrayed by a man as temptress.

The exhibition gives insight into the tension between the accepted and that which was restricted to fantasy, revealing a subliminal aspect of the supposedly polite British culture of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In 1765, after being forced to leave his native Switzerland due to conflict with a local magistrate, Fuseli arrived in Britain, whose status as a fledgling artistic epi-centre was inextricably connected to the commercial middling order – and thus to their obsessive anxieties about “polite” appearance. With the support of Sir Joshua Reynolds, Fuseli spent time in Italy cultivating his artistic potential – the somewhat erratic quality of his sketches can perhaps be attributed to his lack of formal training. In 1799, he was appointed Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy, and later became its Keeper – the institution made tangible the connection between British art production and the fulfillment of genteel appearance. Despite the sensationalism of much of his work, Fuseli projected a superficial image of propriety. In this context of politeness and Fuseli’s prolific role, the exhibition sketches are incendiary.

I move between the picture frames. Permeating the sheets hung on the gallery walls is precisely this tension between polite projection and obfuscated eroticism: Fuseli has made his women at once plausible members of society and sexually deviant. They are placed within the domestic sphere that was increasingly associated with eighteenth-century women – I notice, for example, that one portrays a woman sewing. I look closer and see she is tied to the wall by a leash. Their fashion is excessive: the busts are absurdly low, the hair profligate, and the empire lines pull their waists in before their hips swell outwards in deliberately contrived curves. One courtesan sits placidly, but her breasts are exposed, and a phallus is inked to her armband. Although Fuseli’s sketches appear initially acceptable, closer inspection reveals a salacious urge barely suppressed beneath a veneer of decorum.

The subjects’ postures are artfully arranged to display their figures to the best advantage. In one sketch, two courtesans’ arms form loose arcs that mimic the very curves of their bodies. A common silhouette in his work – indeed, it seems to have been observed with obsessive repetition – displays a woman’s back. The subjects’ contrapposto stances set their figures into luxurious curves, hips jutting. Their arms reach backwards to clutch at their skirt fabric, an act of necessity that nonetheless consciously draws focus to their rears. This was by no means an uncommon practice – in the contemporary Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen’s Mr Darcy notes how women take a turn about the room because “you are conscious that your figures appear to the greatest advantage in walking.” But in Fuseli’s sketches this coquettishness is made brazen. The unobjectionable practise of walking – the polite promenade – is deliberately sexualised.

On the furthest wall hangs ‘Three Women with Baskets, Descending a Staircase’: the foremost subject is practically nude. Indeed, her diaphanous shift is wholly perfunctory – instead of veiling her, it draws more attention to her very nakedness. Her arm is extended, directing the gaze to a pale armpit and exposed breasts, and the languid wrist implies passivity. It is jarring when I realise that her outstretched finger seems to echo God’s own hand in Michelangelo’s ‘Creation of Adam,’ which Fuseli saw during his eight years in Rome. A religious motif placed beside a body so overtly sexualised renders her looseness quietly outrageous. Here, too, the models’ postures are carefully arranged to display their figures, but their nudity pushes them beyond the bounds of politeness into coy exhibitionism.

These anxieties about presentation and the middling order’s culture of self-elevation through appearance are also found in subtle classical allusions. Portraying oneself as educated was a means of achieving respectability, and Fuseli seems no different. In one image, a bust of Medusa stares outwards, fixed not in her coarse mythological stone but in polite marble. Indeed, one sketch is even displayed beside a photograph of a classical bust, drawing direct comparison between the tight curls of Fuseli’s models and the ancient hairstyles that perhaps inspired them. It seems, initially, that he too is attempting to frame himself within this educated, respectable blueprint. I complete another loop of the gallery. With a second look, I notice once again the subversion of this polite culture. In one drawing, the inclusion of the allegory of Vanity is perhaps a commentary on the dangers of pride. In another, the word “Nemesis” has been stitched onto an otherwise tender portrait of a domestic arcadia by his wife. This allusion to the Greek goddess of revenge speaks to contemporary alarm about taking polite appearance to excess. Fuseli’s sketches exemplify this tension between acceptability and subversion, as well as projecting anxieties about appearance.

The exhibition is unsettling but exceptional. The women within the images have a curious degree of agency, dressing their hair and arranging their postures as they please – many even seem to be dominatrices – but they are contrived and then realised by the male fantasy. Collectively, the images hung on the walls of the Courtauld are an intriguing illustration of contemporary anxieties about gender and respectability. Fuseli’s women are fetishised into beings wholly apart, yet plausibly connected to, the late eighteenth century culture of decorum – the sketches indicate a suppressed and often alarming eroticism lying perilously close to this respectable surface. It is little wonder his wife burned them. ∎

Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism was on at the Courtauld Gallery, London, 14th October- 8th January. All images courtesy of the Courtauld Gallery, London.

Words by Eva Stuart.