The Gold Drawings: Evelyn De Morgan at Leighton House

by Eva Stuart | September 13, 2023

As far as is known, Evelyn De Morgan made only seventeen ‘gold drawings’. Eleven of these are arranged along Leighton House’s basement gallery, tracing a filigree thread across the four dark walls. The room is low-ceilinged, and its walls are the same matte grey as the carefully selected woven paper that De Morgan’s symbolist figures gleam upon: the effect, as you slip between the gently radiating frames, is rather like entering a grotto. It is an intimate setting, and it does the drawings perfect service. They glint on the walls like gold inlay.

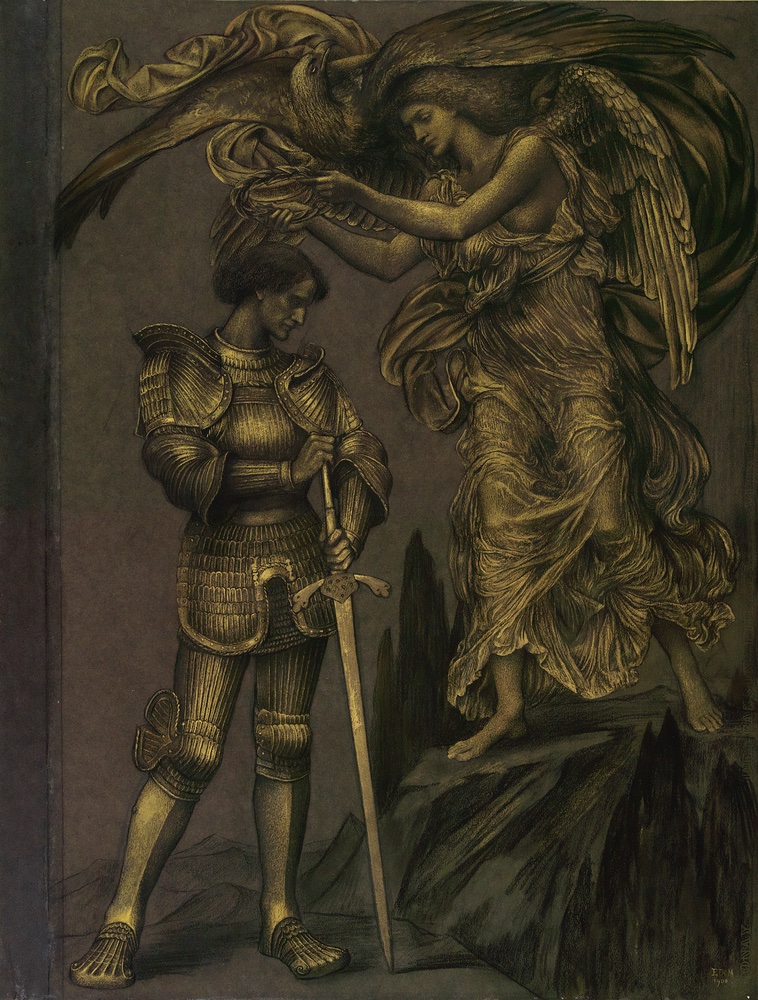

De Morgan was a symbolist painter and draughtswoman of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Her arguably more prolific works– her paintings– reflect the imperatives of the Aesthetic movement, prioritising appearance and beauty over the functionalism endorsed by the late Victorian emphasis on art’s ethical and instructive purpose. De Morgan was a non-conformist: as a young woman, she rejected her privileged lifestyle and refused to ‘come out’ in society and her later works urge pacifism against preoccupied British militarism in both the Boer War and the First World War. Her adherence to the symbolist principles of metaphor and allegory makes her work but one tangible aspect of a consistently recusant profile. The gold drawings are magnificent examples of her artistic priorities, welding together her experiences of the Italian Renaissance from her time spent in Florence with her ceramicist husband, William De Morgan, and her focus upon the spiritual.

This spiritualism permeates, emerging to the viewer though the complicated allegories depicted. In Mercy and Truth Have Met, Righteousness and Peace have Kissed (undated), the abstract concepts of Psalm 85 are personified into golden women. Visually, they are exquisite – their faces are sensitive yet defined, deftly sculpted in gold monochrome, and they illustrate her awareness of tone – but they are not merely evidence of artistic capacity. Serene and effigy-like, they emphasise the notion of God’s salvation brought to Earth. Expression of these themes is enabled further by the gold De Morgan used: in The Soul’s Prison House (c.1889), a bowed figure radiates, implying a precious salvation, whilst the black chalk setting around her is earthly and dull. De Morgan’s ingenuity is evident in the streak of silver used to depict the scroll the woman clutches. Containing the words of St Augustine of Hippo, this scroll is immediately the focal point as the streak of cool metal bifurcates the warm gold. De Morgan’s artistic influences are varied, but the exhibition allows room for each of them to become apparent, and her indebtedness to the Italian art she encountered is evident without being overwhelming. There is a neat continuity between the depiction of St Francis of Assisi, derived from Giotto’s fresco at the saint’s basilica, and the more subtle allusions to Andrea Mantegna’s Instruction of the Cult of Cybele at Romethrough the terracotta chalk sky in her The Valley of Shadows (1899).

The very medium used – crayons of her own invention – speaks to her intense spiritualism. Well-chosen text upon the wall confirms this: she knew of the Swiss Renaissance alchemist and philosopher Paracelsus, who believed gold to be the colour of salvation, and this broader cultural and spiritual dimension of gold is employed effectively in the drawings to emphasise allegorical and religious subjects alike. It gives them a sanctity that colour perhaps could not. De Morgan made the crayons herself, from dry gold ‘cakes’ bought from the artists’ supplier Charles Roberson and fashioned into drawing implements similar to those used by Edgar Burne-Jones. The support is a grey woven paper: the selection of grey, and not black, gives the piece a softness that mutes the chalk pastels, allowing the gold to gleam, and indicating her sensitivity of tone. Her figures quiver as they catch the light: they are beautifully animated.

Most of the drawings are finished works, but one is a preparatory sketch, and this Study of an Angel (undated) is a useful inclusion in illustrating De Morgan’s working methodology. Dark chalk creates the outline of the figure and landscape, before yellow and white chalk highlights are added. Dry gold paint is then worked over the top, layered and built up in a somewhat sculptural approach to create varied tone and a highly realistic sense of physical depth. The works on display are both experimental and accomplished – De Morgan herself noted the difficulty of her technique because “no erasure could ever be made”. In Victoria Dolorosa (1900), the soldier’s armour is clearly rendered, its panels of hard metal directly contrasting the membranous drapery billowing around the angel beside him. The materials are convincing and almost tactile, and it speaks to De Morgan’s ability that she could make a single monochromatic medium evoke such textural variety.

The exhibition foregrounds De Morgan’s gold drawings without giving the viewer a narrowed understanding of her ability. The intentional absence of paintings illuminates a selection of De Morgan’s oeuvre that is not only often overlooked but that, in itself, offers significant understanding of her innovation and non-conformity. Broader context is available through well-phrased accompanying text panels, and, as such, the drawings avoid seeming isolated or parochial. Instead, it seems a joy that they are being exhibited as artistic works in their own right. The gallery itself certainly helps to justify the presentation of the drawings alone: the low, alcove-like space allows the works to dominate, and the figures quietly shine against the grey walls. They do not need accompaniment – indeed, colour would ruin the sacrosanct feeling the gold invokes – and the effect is highly compelling. The exhibition is a neat defence of the case for specialised shows.∎

‘Evelyn De Morgan: The Gold Drawings’ is on at the Tavolozza Drawings Gallery, Leighton House, until 1st of October 2023.

Words by Eva Stuart. Photography courtesy of Leighton House.