Repatriation and Reconnection: An Interview with Saba Qizilbash

by Imee Marriott | February 8, 2023

Saba Qizilbash is an excellent storyteller, which is fitting for an artist whose work is so concerned with narrative, from the interrogating and reworking of old narratives to weaving together new ones from the fragments of neglected histories. Burrowed into a corner of Blackwells’ Caffè Nero, she speaks softly and meticulously – her words charting topographies across South Asia, the Middle East and the Arabian Gulf.

She is the winner of the 2022 Emery Prize, and her solo exhibition ‘Routes of Desire’ is currently showing in Pembroke College’s Art Gallery. The artist (a recent Ruskin graduate) has shown her work all across the world, but her creative narrative began in her childhood. Though she now lives in Dubai, Qizilbash was born in Pakistan and raised in Abu Dhabi and Lahore, where, as a motivated pre-teen, she would set up still lives in her room and practise “drawing in a very vigorous manner”. Qizilbash emphasises that by the time she reached her GCSE years, it was evident that “I just had to be an artist … there was no other alternative path for me”. Studying as an apprentice with a senior artist in Pakistan, she describes how it “of course involved them insulting you, and telling you you were good for nothing”. She toiled through the demanding and “very, very traditional” curriculum of the National College of Arts in Lahore, before continuing to the Rhode Island School of Design, where Qizilbash developed the craftsmanship and eye for observation evident in the detail of her large-scale graphite and pencil drawings.

Success was not instant, however. Qizilbash speaks candidly about the difficulty of her career upon graduation, reflecting that “you feel very excluded, it’s a very lonely state of your career”. She describes years of dismissal by art galleries, and the exclusionary nature of Dubai’s grassroots art scene, but locates a turning point around a decade ago when a transformative experience in her family left her unable to use acrylic, her primary medium. “I ended up destroying a lot of my canvases, I questioned my concepts, and my path, and my creative journey and then I picked up a pencil and I began to draw again…So I untaught myself how to paint and I taught myself how to draw.” It was with this shift that her illustrative journeys began. Her fingers skip beside each other on the table in imitation of a person’s stride, while Qizilbash explains that, full of visions of communication issues and transport breakdowns, “I began to try to walk my way back to my country, Pakistan, because I felt like I needed to go back home, and I couldn’t”. Using road maps, Google Maps and Google Earth, Qizilbash started to draw her route back home, from Dubai to Lahore.

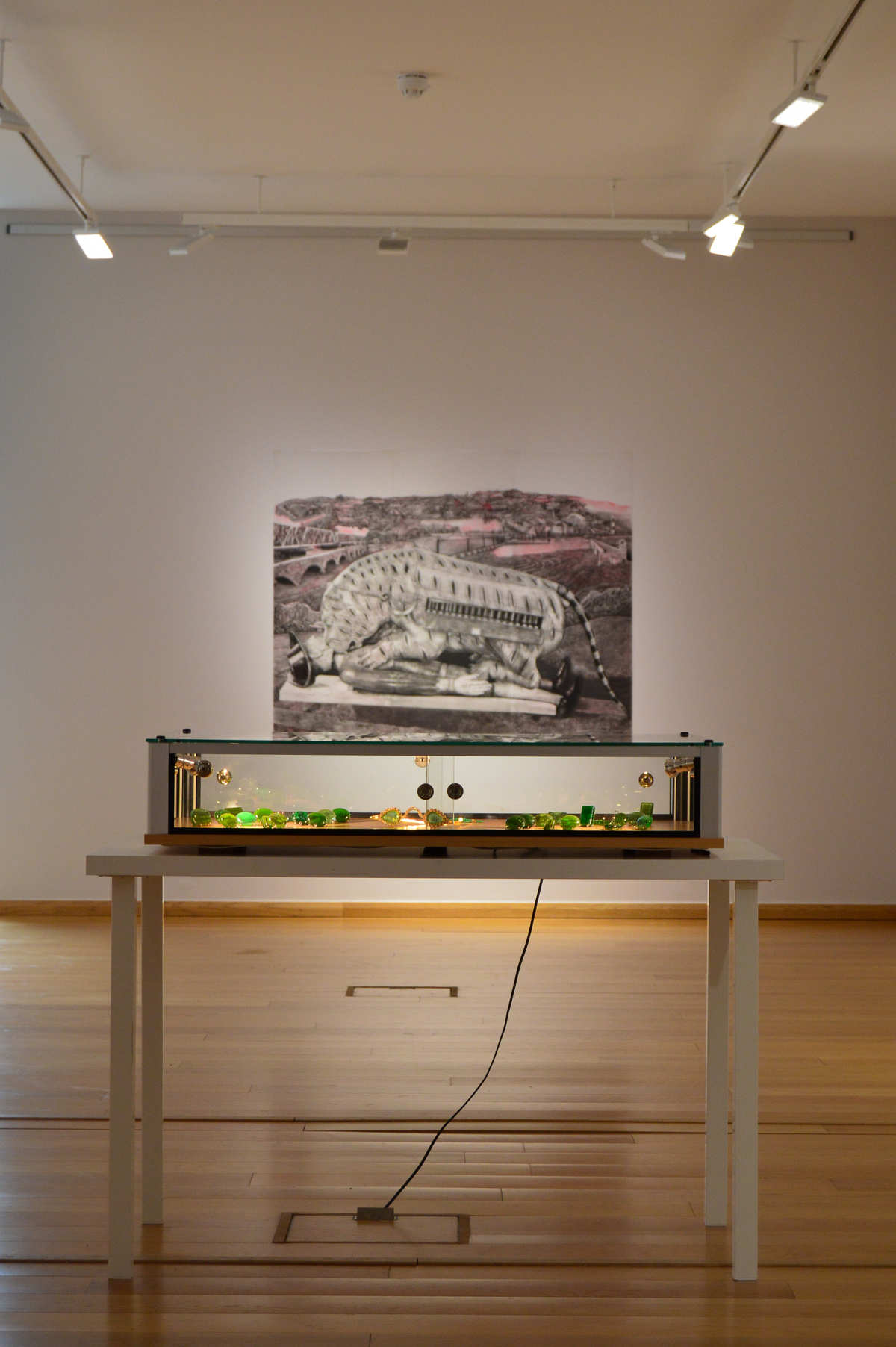

This innovative way of sketching how to return home is one of my favourite works of ‘Routes of Desire’. In a 122 x 152cm graphite drawing, at the end of the long, rectangular space of the Pembroke Art Gallery, a mechanical-esque tiger mauls a European man; in the background, brigades, forts, temples and palaces intersect and overlap. This is Qizilbash’s “Repatriation of Tipu’s Tiger”, and its conception lies in a guided tour of the V&A Museum. The tour culminated in a discussion of how the museum could better contextualise one of its best-known objects: the semi-automaton tiger and its soldier-prey, looted from the treasury of Tipu Sultan, who was killed by the British East India Company army in 1799. I sense Qizilbash’s frustration as she recounts the responses from their discussion group, including suggestions that the artefact should be made more accessible to children. “There is a danger”, Qizilbash recalls thinking, “of turning this into the tiger who came to tea … [but] it has a violent history. Someone was killed, his entire family was kept hostage for a year, and they were displaced and removed from history at the time this tiger was taken away from this palace.” As for her response to the question of what to do with this colonial trophy, her answer is definitive: “this needs to go back”. She acknowledges that this isn’t a simple solution, questioning what the current Indian government would do with a symbol of Muslim resistance to the British, but she remains firm in her conviction: “let it go through that process, [and] if it is destroyed in that process, that’s where it could be. But it cannot be a trophy that’s incarcerated in a museum, generating revenue.”

Animated by her visceral reaction to the object, and frustrated by her inability to actually return Tipu’s Tiger, Qizilbash turned to her art. “I believe in the power of manifestation through my drawings,” she says, “so I visualised the repatriation of Tipu’s Tiger back to its home town where it was taken from.” Using the journals of Henrietta Clive (wife of Lord Edward Clive, Governor of Madras), which trace the looting of the original artefact and its displacement to Britain, Qizilbash’s illustrative route ends at the site of Tipu Sultan’s destroyed palace, where a museum now stands housing a placeholder for Tipu’s Tiger.

Qizilbash isn’t just concerned with weaving alternative, utopian narratives and journeys, but also with resuming those that have been interrupted. Discussing the artistic property of South Asia that is now housed in British Museums, she argues that “these objects, when they were taken away from our region, they interrupted an evolution of design making, … so I feel an urge, or desire, to pick up and bring back, through replicating – whether through drawings or the making of objects – and bringing them back and displaying them in India, in Pakistan, so the people of our land have access [to them].” This desire manifests itself in ‘Repatriation of Tipu’s Tiger’ but also in Qizilbash’s ‘Chasme Badoor’, a hand-crafted pair of golden spectacles, which replicate a seventeenth-century pair titled ‘Astana-y-Ferdous’, reputedly the property of a Mughal prince. Qizilbash first encountered the glasses on social media, when a photograph of Scottish historian William Dalrymple posing in them went viral. I sense the urgency and frustration in Qizilbash’s voice as she describes her reaction to the photograph, pointing out that “the kind of access that he enjoys is the kind of access I will never have”, despite her strong sense of identification with these objects and their histories. As Qizilbash set about making her own pair of spectacles, a controversy involving Pharrell William’s uncredited appropriation of the design for a collaboration with Tiffany “added another layer” to a project increasingly imbued with questions of appropriation and access. After all, Qizilbash reminds me, only a small number of people from her homeland can access precious South-Asian objects – housed in auction warehouses and European museums – in person.

Intending her glasses to function as a vision corrector, Qizilbash has embedded graphite drawings of refugees from the 1941 Partition in resin in place of the emerald lenses which characterise the original. At the start of our conversation, Qizilbash emphasised how much of her artwork is connected to the Partition, and the present-day implications of colonial interference in South Asia. Her research interests led her down roads connecting the nation-states of the region, charting her homeward journey from Dubai to follow the conquest route of Mohammed Bin Quasim, as well as the eighteenth-century diplomatic mission of Tipu Sultan. Qizilbash found her attention drawn to the gaps – the No-Man’s Land between borders. “Erasure of occupancy in the No-Man’s Land has been a huge interruption to the flow of religion, trade, culture, people, language … and I realised that the fence, if I pushed them down, they act like staples – you can sort of push them down into the land and hem that space and open it up for open access. So I began to do that in my landscapes and began to visualise connecting dividing land”. Qizilbash’s desire to visualise the connection of divided land stems from the fact that “[my] identity is very tied with undivided India, and pre-migration India”, as well as a sense of the urgent need to record the “horrific stories” of Partition. Speaking tenderly of her grandparents, she explains that “I have tried to excavate their stories [to] try and write about them and I have a lot of objects that they carried with them when they crossed over, so I’ve used them, the material memory of those objects and tried to record as much that I can.”

A waitress approaches our tableto let us know the café is closing soon. As we take our last sips of tea and coffee, I ask Qizilbash what she hopes people take away from her art. She pauses to consider the question: “I love invigilating the space when I have a show opening, and watching people look at my art, and what I enjoy the most is them being still. Because I’ve noticed that my work makes people stand and observe for very long durations. And I see them walking through the path that I walk through in my drawings … to be able to hold their attention long enough to be moved in a certain way is what I hope for my viewers.”

Two days after the interview, I am perched on a stool in the corner of the Pembroke Art Gallery, an Invigilator’s badge clipped on my jumper. I am used to keeping a half-eye on the patrons who enter and circle the gallery, phones at the ready. Today, however, something seems to siphon the urgency out of the medley of visitors who flow in through the Brewer Street Doors, interrupting their usually swift circuits. Instead, they wander, pause, look, and look again – and remain still. ∎

‘Routres of Desire’ was showing at the Pembroke College Art Gallery, Tuesday 31st January – Tuesday 7 February 2023

Words by Imee Marriott.