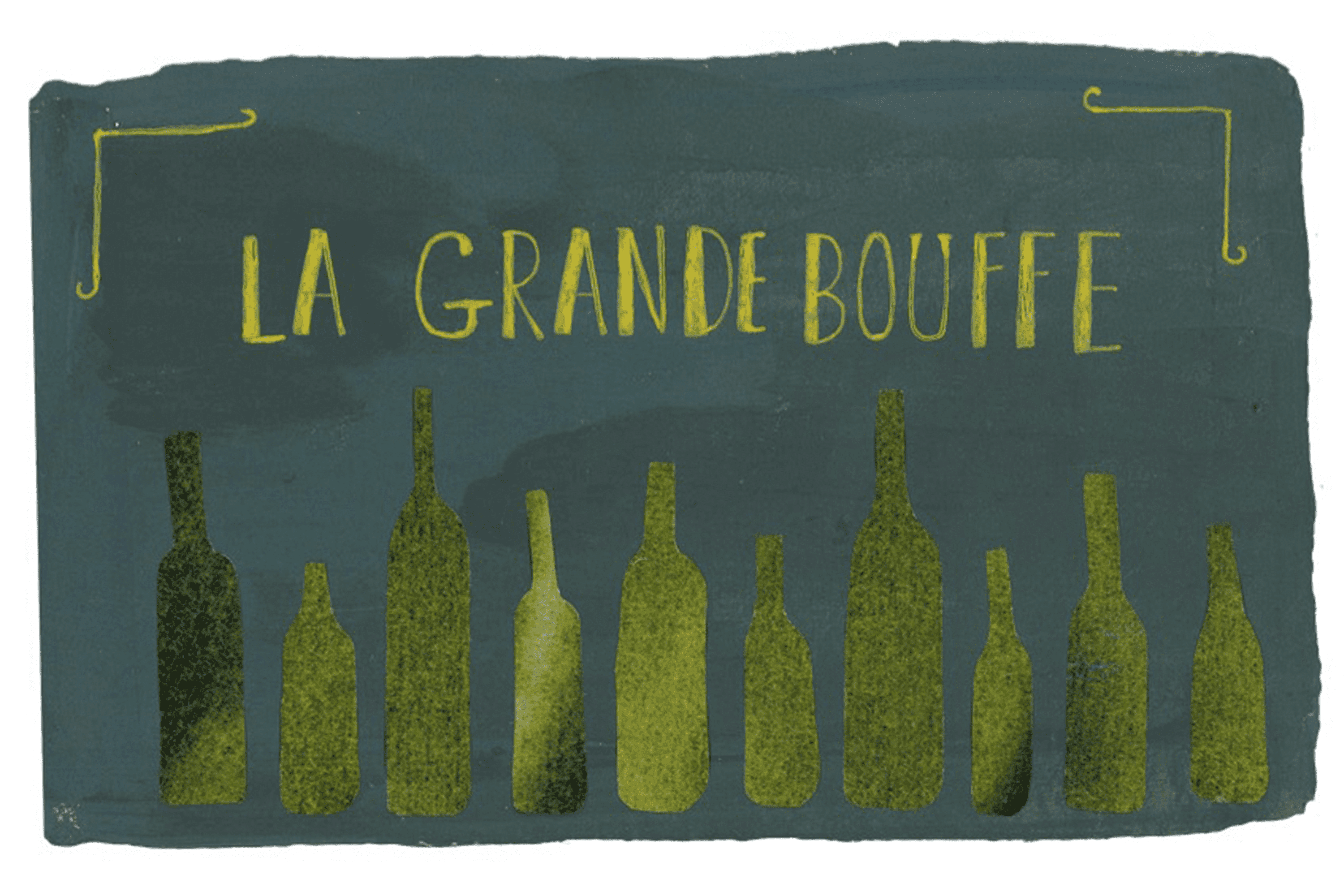

La Grande Bouffe

by Isaaq Tomkins | September 6, 2022

There is no fate worse than dying with a fully stocked wine cellar. He wasn’t sure where he’d read that, or if he had come up with it himself, but he took those words very seriously. As did they all. There were four of them in the dining room of Château de Montbrun: a Butcher, a Banker, himself, and a local journalist. Of course, there were others scattered around the place: chefs, waiters, a porter, and the like. They’d organised everything meticulously. The food would be delivered via a dumbwaiter into the long narrow room, and nobody would stop eating until it was over. The journalist had agreed to document the affair on the condition that he would not interfere under any circumstances – the Banker suspected that it was morbid curiosity rather than journalistic integrity which prevented him. The reason they had gathered was simple. They were all going to die at some point – some sooner than others – but they had mutually agreed that they’d all like to go on their own terms.

So, there they were. For their first course each man had jambon cru fumé with brown mission figs, goat curd, rocket, and candied walnuts. In the centre of the table sat a bottle – a Balthazar of Clos des Mouches, twelve litres in total. It was advertised as dark and oily with a silky texture and aromas of pepper, tobacco, humus, and undergrowth. A silence settled around them. He wondered how to start them off. Should he say grace? Or perhaps just shout “Bangarang!” and let them all tear into the food with their hands? The Butcher settled it for them all by reaching out and pouring himself a drink. In fact, he struggled to lift the Balthazar, so the journalist ran over to help him, but eventually he poured out three glasses, albeit with some spillage. They toasted to nothing in particular, and dug in.

There was no overarching logic to the order or choice of food because none of them knew how long the affair would last. Rather, each man chose a series of his favourite dishes, which were sent up to the dining room as they were prepared. The first course was quickly followed by boeuf bourguignon, which must’ve been the Butcher’s choice since he took to it with such zeal, bringing forkfuls to his mouth. The Banker liked it, but he didn’t care much for the dish personally – though he did enjoy the sliced carrots, which had been quickly simmered with fresh orange juice, honey, ginger, dried currants, and some spice which he couldn’t quite place (it was turmeric, but that was beside the point). The first few courses were difficult. Despite the brave faces and lofty comments (perhaps spoken a little too forcefully) they were scared of what was coming. Perhaps it was nerves. In any case, once the procedures began in earnest, they took to the task with vim, devouring each course with ease as it came at them, like cows swatting flies with their tails.

The day wore on and more food was brought. At some point, Bouzigues oysters with mousseline sauce, parsley crumb, and foraged sea herbs were sent up in the dumbwaiter. With them came a bottle of 18-year-old Talisker whisky and three crystal tumblers, each containing a perfectly transparent sphere of ice. The glasses were so chilled that condensation formed on them, wetting his fingers ever so slightly as he passed two of them down to his companions. The cool sensation of the glasses made him realise how hot he had become, holed away in that long, narrow room, and he instinctively brought his glass upwards and pressed it against his forehead. Slowly the room seemed to come into focus, and he surveyed it, taking in all the elements together. He saw the journalist in the corner, eyes trained on his notebook, only glancing up briefly to check on their progress. He saw the Butcher slurping down his oysters – his pace had slowed since the beginning of their adventure, but he pressed on. He noticed the Banker had abandoned the present course in favour of a more impressive feat: he had a block of Emmental in front of him and was carving off chunks and placing them onto a raclette grill. (Did he bring that from home?) He then began to pour the cheese over everything in front of him before stuffing it into his mouth. Gnocchi, potatoes, and tomatoes were all being covered in cheese and shovelled into his face.

A wave of nausea came over him. By this time the heat from his head had begun to melt the ice in his glass and he had no more desire for clarity anyway, so he hastily poured some whiskey into the glass and gulped it down.

At this point a tray with some cakes on it had been brought in, at the centre of which was some unidentifiable figurine in a toga (an emperor perhaps, or maybe a god?). He pitied whichever pâtissier had laboured over it. The figure had a tasteful arrangement of orchard fruits in his lap: apples and plums, damsons and dates – all sorts of sweet delights. He expected the Banker to say something grand, but no words came, so pausing only briefly, he reached out to take a handful of fruit. At the very lightest touch, however, the cakes and fruit would spurt out an unpleasant saffron-infused syrup which had mixed with the juice, just missing his mouth. The Banker stared at him triumphantly. Ignoring the Banker, he grabbed fistfuls of fruits straight from the figurine’s lap, tilting his head back and squeezing the nectar into his mouth. Then, for a brief second fuelled by the Banker’s fading smile, he brought the tray over to himself and began to lap at the spilt mixture like a dog. The Banker looked at him indignantly but did not comment.

Up in the dumbwaiter came yet another dish. It was relatively simple – a leg of Welsh lamb with crispy roast potatoes, parsnips, and carrots on the side. He recognised it as his own request. The lamb was from Cigydd Butchers in Aberdyfi, where his family used to holiday when he was a boy. It was one of two butchers in Britain where the lambs were killed on site, and their meat was the best he’d ever had. He thought it would be a comfort, but now, with his belly already bloated from the other courses, he looked at it with dread. The lamb, having been transported across the Channel, had lost any particular freshness it might once have had, and it barely registered on top of the lingering flavours of his previous courses. He should’ve left it where it was, an untouched memory. His trousers were beginning to feel tight now, his heart pumping away like a locomotive going up a hill, and he suddenly felt constricted in the ready-to-wear suit he’d picked for the occasion. His tie at some point had found its way into a puddle of gravy. His twill shirt was untucked, the top button undone. To hell with it, he thought, and tore it all off with a sudden urgency – the tie, the shirt, the textured blue jacket, all of it – until he sat in his underwear, out of breath from the frantic exertion. Now, when the fat dripped from the meat and crumbs flaked off into his lap, he thought nothing of it: the charade of decency had been dropped.

Like men enraged, each of them attacked their food. His knife sawed away at the lamb, and his fork intermittently screeched on his plate as he stabbed and scooped at his peas. At some point a large ceramic pot was knocked to the floor, crashing down and scattering itself in all directions. He only registered it when he felt a shard of porcelain digging into his foot under the table. The Banker was gouging out great hunks of bread and chewing them noisily. The Butcher was still, slumped back in his chair as if to say, “I’m stuffed”. The two men who remained ripped away pieces of meat and shredded them, and then they gnawed at the bones, and they sucked out the marrow, not considering for a second what they were eating. And the journalist just stared. ∎

Words by Isaaq Tomkins. Art by Rachel Jung.