FOR THE PARTY, NOT THE NATION

by Alex White | April 18, 2017

The Conservatives may be ready for a general election, but the country isn’t.

In the past week, the Conservatives have been placed twenty-one points ahead of Corbyn’s Labour Party in two polls. Many Labour MPs have accepted that not only do they face no real chance of forming the next government, but that a good number of them will lose their seats in the next election. In conventional wisdom, it is not a big surprise that Theresa May would call an election to catch the unprepared Labour Party off-guard, giving her a strong mandate for her own premiership.

These, however, are not conventional times. Politics is always about big questions, but the questions facing Britain in 2017 seem even bigger, almost existential. It’s not just about Brexit—although trying to discuss any political matter now without mentioning it is near on impossible—but about the nature of our union of nations and our democracy. Even the peace of some of our territories is in question. It may make sense for Theresa May as leader of the Conservatives to call a general election, but it doesn’t make sense for Theresa May as the leader of our government.

It can be easy to look at England and question what would be so dangerous about a general election. However, this isn’t an election taking place just in England, but in Wales, Scotland and, crucially, Northern Ireland too. Stormont is currently still suspended. The Unionists and the Republicans have still not reached any agreement on returning to the power sharing executive. Direct rule from Westminster still looks like a real possibility. Northern Ireland has already gone through a bitterly contested assembly election as recently as the 2nd of March. If power sharing is to be restored and Stormont to return to its everyday business, there needs to be a focus on fostering consensus, unity and compromise. Elections are noted for doing none of these. All the gains made from the Good Friday agreement are facing one of the greatest challenges to peace in Northern Ireland. By calling an election in the middle of this Theresa May is showing a disregard for the precarious situation existing in Belfast in favour of gains against Labour in the English heartlands.

There is, of course, Brexit. Brexit has underlined every major political question since the vote in 2016. It will continue to dominate politics for the next ten years as Britain comes to terms with its exit from the European Union. Whether Brexit was a good idea or not and what kind of Brexit Britain wants to see will be the one of the major campaign themes. Everyone, no matter which side they voted for, wants to see the best deal. The only certainty about the whole procedure is the time we have to do it in. The time scale for Article 50 is twenty-four months. Six of those months at the end are dedicated to passing whatever deal is agreed on through the European parliament and the assemblies of the major states. Clear and bold leadership is needed to steer Britain through those negotiations where time will be of the essence. It’s hard to see how this can be provided when—for at least six weeks—the key ministers will be running around the country campaigning and focussing on winning votes from Labour instead of Britain’s relationship to the single market. These are intelligent people; they can focus on more than one thing at once. But the defining issue of our generation deserves more than sharing attention with party politics.

Brexit and the continued political instability in Northern Ireland mean we do not live in conventional times. But even when politics was ‘normal’—and to a certain extent predictable—snap elections have always been slightly dubious. The ability to call an election whenever the Prime Minister chooses has only ever been used to advantage the ruling party. Yet this occasion seems particularly questionable. Theresa May has consistently said she would not call an early election and many people believed her. Due to this, there has been very little drive to get people registered to vote. These drives can last months and start well before the six week official ‘short campaign’. We now have fifty-one days until the election itself and the deadline for registration is usually about two weeks before. Of course, ideally everyone should be registered to vote anyway. But people move, people forget, and often people just don’t bother unless prompted. This is especially true of young people, due to woeful political education in schools and the remarkable inability of politicians to connect with the young. Before the European referendum, there was a sustained campaign in Oxford to get students to register. It’s hard to see how that can happen on less than fifty-one days warning. A sudden snap election doesn’t give as much time for registration drives, for campaigns, for education and information. In the pursuit of more votes, the Prime Minister is limiting the opportunity for some people to vote at all.

This will be amongst the first of many column inches on the election that you’re going to read, and it’s only the first day. You’re going to be bombarded by Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Snapchat, Instagram—not even your Tinder will be free of it. Such is the joy of democracy. But it is difficult to see the joy in democracy when it puts the interests of a nation at risk and disenfranchises that nation’s own people. Theresa May has a lot to win from this election. It’s entirely possible that she could put Labour out of power for a generation with a decisive victory. Yet by doing it she is risking the prosperity, peace and liberties of the citizens she is meant to represent. A general election makes a lot of sense to the Conservative party, but it makes a lot less sense to the interests of Britain. The country isn’t ready for the election in June and as our Prime Minister, Theresa May should have recognised that.

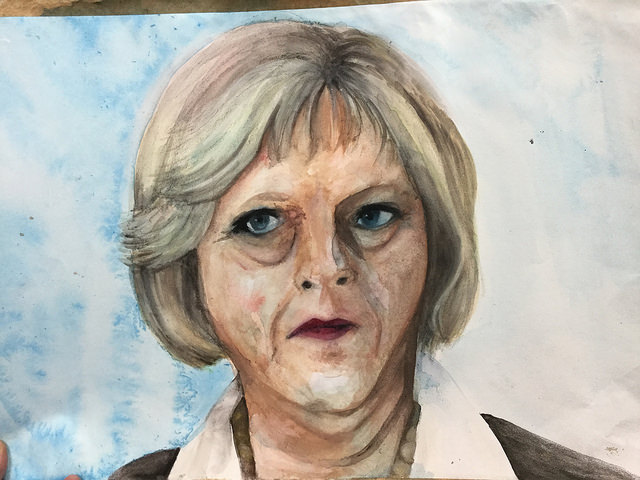

Photo: Flickr