Catherine

by Words by Beth Simcock. Art by Liz Tiskina. | January 2, 2021

One of the women I worked for when I first moved here was also named Catherine. She lived in one of those pretty Georgian terraced houses in an expensive suburban fold of the city that I never usually found cause to visit. The front entrance to the house was through a narrow feature door that for several months trapped a lilac thread in its hinge from the blouse sleeve of Annie, the Tuesday assistant nurse. It was a cold place, but still I grew fond of it.

The other Catherine was kept like a geriatric Rapunzel, bedbound in the attic room at the very top of the house; four and a half flights. This climb I made twice each weekday and every other Saturday. Once a week I was trailed in my footsteps by Annie’s lurching stride, with each one a ‘huh’ noise like the tail-end of a question: another? I imagined it was hard for her to breathe properly because most of the air that it takes went into inflating those breasts which were like party balloons under her uniform button-up.

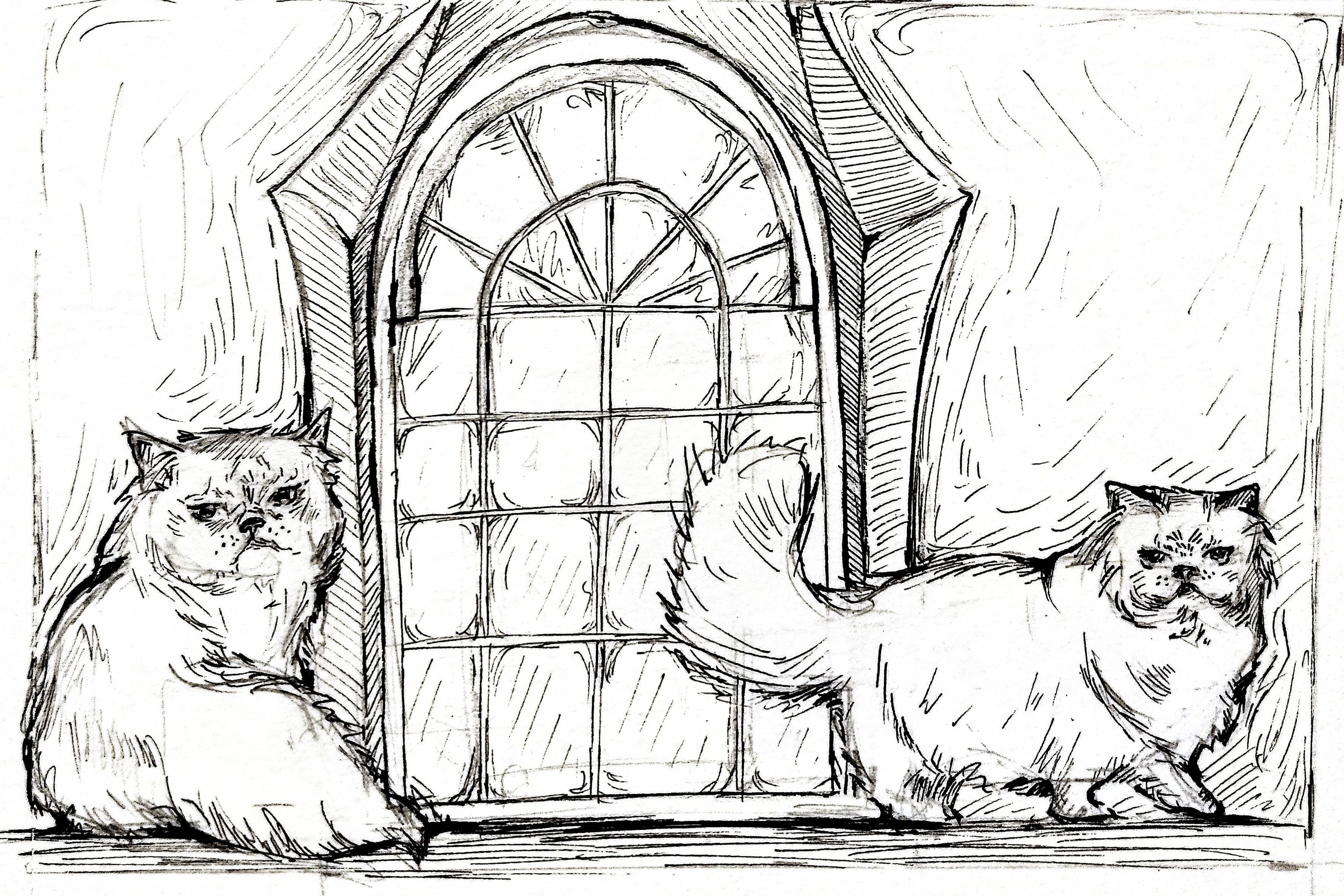

Catherine’s room used to be a library. Arched windows in the far wall leaked a blue-grey dishwater light over the sparse dark wood furniture. In the daytime the low-vaulted ceiling and bookshelves held diamonds of that shivering wet colour, like the reflections on the surface of an indoor swimming pool when you are underwater and looking up.

The first time that I took back her paisley patterned blanket to bathe her, I was shocked by the white tufts of pubic hair that grew out of her like desert grass. It had never occurred to me that that might happen to you. I later learned that it often falls out completely. Eventually you come to your grand old age bald and wrinkled like an infant – such is the supreme irony of living, I am told.

Her skin was an unruly pink all over, just like the pickled things in jars at the Middle Eastern grocery store. Her image was a little slack; the likeness of a close friend drawn fondly but inexpertly from memory. A bleached photograph at the bedside showed her as a grinning young woman – too many teeth and the same long, fine hair blown soft about a handsome face. The type of pretty girl that you want to make laugh. She liked to have her hair brushed each time I came over – hard, with a heavy gold paddle brush. On special occasions I would braid it with a ribbon like the tail of a prize pony. We found many special occasions between us – full moons and half-birthdays, religious holidays we knew only by their names under the date on the weekly flip calendar.

While I fussed with my brushing or sticking the bright blue incontinence pads to the crisp ironed sheets, she would talk to me. She had few other people to really talk to. The only other person living in the house was the youngest of her adult sons. Charlie was late into his 50s and hadn’t yet graduated to ‘Charles’. The nurses and I regarded him between us as an asshole of the highest degree. Charlie brought with him for company a string of thirty-something-year-old girlfriends with tasteful gel manicures and PA jobs in the city, each new shampoo bottle lasting only a few weeks or months on the bathroom shelf until the inevitable door-slamming flurry of khaki trench coats and expensive acid-wash jeans marked the changing tide. And then there were two dozy slat-eyed Persian housecats: Elvis and Prissy, bought for company by a well-meaning relative as a gift to Catherine, who diligently took a daily pill for her allergies. The cats she loved dearly and they never left her bedroom.

The two of us talked the way that people talk in arthouse movies – little beats between each question and answer. She would stroke one of the cats over her chest and ask me things like if I had a favourite song (I didn’t), or a boyfriend (I didn’t) or hunch about how I would die (yes, I had always harboured a tender fear of deep water). She told me that she had always believed she would be savaged by animals; this was why she had never been to the zoo.

I said that she was lucky to have escaped her fate and she said: “maybe, but now I think I would’ve liked to see a penguin.” We left it like that. She had a maddening way of just ending conversations where she chose. This was an infectious habit and so it happened that our conversations stopped and started like passing sailboats on a still lake.

One afternoon I brought up a letter addressed to her, a large cream envelope that I tripped over on the threshold so that it bore the print of my plimsoled foot across the front. It was a little different from the mail I usually read aloud to her; postcards from tropical destinations from her other children – glib tales from sunny all-inclusive resorts in Aruba that she received with the appropriate smiles and eye rolls. This new script was a terribly romantic letter from a high school boyfriend who had discovered that she was still alive and wanted to reach out before he died, which would be soon. My reading made her deep eyes glitter over. Prissy, whose turn it was lying over her breast, found her grey marabou tail constricted in a tight fist.

This was probably the first time that the fact of her dying had really occurred to me and it felt something like waking up with concussion. It made my stomach ache to know that she wouldn’t be able to leave this house or this room, where her teeth floated in a glass beside her bed like a poisoned goldfish, until she was cold dead. I thought often of her little sick-bird body, of her insides slowly puddling to mush in there. If I lifted her to her feet, I was sure her flesh would just slide off the pit of her, like the soft part of a rotten fruit.

I cried stinging crocodile tears for the wide-armed running TV-soap airport reunion that I wanted for her and the dying ex-boyfriend from the letter. I knew that she would have taken a cashmere slipper to my head if she had had the strength; she hated crying, and it didn’t do to be so pathetically romantic.

Life took place in those quick hours somewhere between the bed and my little reading chair and the view out of those glass arches – the dull-bricked backs of other people’s houses; wives of lawyers suntanning pale breasts in their backyards, and teenagers throwing loud, late parties, and starting ill-fated rock bands while their parents are out of town. The fat-fingered bloom of magnolia trees hung sweet over garden fences; leaf blowers and games of hopscotch turned to far away and simultaneous colliding stars. Then it was back to evening and our two bodies in a strange room, quiet enough but for the occasional passing car far down on the street and the two cats purring fat and constant at her lap.

“For me it’s like this all of the time.” You learn to feel things from a distance.

I wanted so badly to plan an escape for her.

In the last few days of Catherine’s sickness, the family asked that I didn’t make my visits anymore and gave me the week’s pay in advance. I waited, thinking of her, and all of the universe carrying on around her in its usual way, and how much she would hate the fuss.

When the phone call came it told me that I could come to the house after the memorial service, if I liked. I arrived to a room full of people whose names I only knew from the postcards, all with the same sloped nose. The smell of a new plug-in air freshener perfumed the funeral small-talk – it was her time to go and what a shame that Sarah had to cut her holiday short.

After I had eaten enough cold appetisers to want to leave, Charlie stood up and grabbed me by the arm. He said that he had never liked cats and would much rather I take them home with me, if I wanted, because they preferred me anyway and he knew I lived alone. A teary, mute girlfriend nodded toward the kitchen, where I saw two stacked cat crates and a plastic shopping bag full of collected animal paraphernalia propping open the door. I cried all the way home in the taxi with them beside me on the car seat.

That night I dreamt of being mauled by a tiger. When I woke to small rough tongues between my toes, I took both cats in my arms and brought them to the garden, where I intended to set them free. The animals tripped into their brave new world like new born lambs before the rising sun called their soft bodies sweetly to the warming dirt. Lying supine in the first yellow light of the morning, Elvis rolled his dark belly skyward and thought, I imagine, something about how good it is to be alive. ■

Words by Beth Simcock. Art by Liz Tiskina.