Les Uzetiens

by Annie King | January 13, 2020

Marie Moreau, wife of the fishmonger, was fifty-four years old, childless, stout, and unimaginative, and had lived at number 31, Rue Jean Jaurès, for each of those fifty-four years. For her, the sweetest moment of the day was her cigarette on the balcony of her late mother’s house, forbidden when the old woman had lived there and forbidden now that her husband did. Marie’s life had been a series of decisions made by other people, including that of le maréchal Pétain to sign the armistice and thus throw in the towel and, most devastatingly, that of her father to give her to a balding man who smelled like something pickled and whose eyes bulged like those of his fish. Marie was not a bitter woman. She ironed and cooked and washed and moved about her day with no complaint and no sound, save the creaking of her knees. For a woman like Marie, the decision to smoke a cigarette (tobacco rations allowing) on her balcony at twenty past nine with the sun on her face and the sound of the alien city in her ears, watching the sway of her pansies in the window-box – well, that was more important than any number of Assemblée-issued decrees. This moment was a treasure because it was hers, and for five minutes of the day, she was living a life that she had chosen. Marie Moreau was an ordinary woman, and so demanding more than five minutes to herself was pure self-indulgence. She was a woman, not a saint, the latter being far more admirable.

The Rue Jean Jaurès was narrow, lined on both sides by pale limestone houses which seemed to lean forward conspiratorially to catch whispers from each other. Marie’s house was no exception, and it found itself in conversation with that belonging to Sévérine Durand, a dumpy woman with a sharp nose and a sharper tongue, whose pleasures included rubbing black-market lotion into her carbolic-worn hands, peeling the paint off her window shutters in large strips, and sneering sardonically at her neighbours. Her life was much like that of Marie Moreau, except for the fact that her husband, six years her junior, had been called up and killed pushing back the Germans; this had painted her countenance with a few more wrinkles and dusted her hair with a little more grey, and she lived under the mistaken impression that she had, when married, been happy, which gave her the luxury of bereavement to blame for her discontent. Perhaps for this or perhaps for her talent at the practice, when she happened to venture out onto her balcony at the same time as Marie, she delighted in bestowing on her an acid comment or two. Because Marie’s balcony-time was the sweetest moment of her day, to have it thus molested wounded her immensely; the guttural back-and-forth which ensued was a fairly regular occurrence, and it was this which Joseph Macleod heard and rejoiced over as he walked beside Arnaud on his first jaunt into town.

“In my house,” Joseph remarked, “everything is cold and still and quiet, and you can barely breathe. This town, this life of yours… it’s quite the opposite. Everything is alive, these people are all movement and vigour!”

“Mmm.” Arnaud, who could understand the barked argot of the women in question, bit his lip and walked by wordlessly.

The world they stepped into was not at all the same which Joseph had seen the night before. All was ensoleillé, and without the distortion of hunger and fatigue, the streets were lent a new and inescapably cheerful aspect. The cobbles which divided the streets, to Joseph, seemed quite limned with gold. Just as the silence of the night had been laced with the sleeping of the city, the music of the morning was being played by the Uzétiens. The trundle of misguided cars could be heard at a distance, pierced by the yells of vendeurs; and somewhere, the frail sound of a busker floated through the streets towards them. The noise of the rest of the town was too great for them to catch any words of the song, but the hoarseness of that woman’s voice seemed to brush roughly off something in Joseph’s heart.

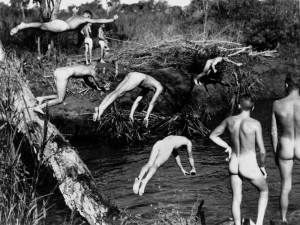

The glimmer of emerald caught his eye first as they turned into the square. It was a canopy of green, created by plane trees with their boughs softly drooping, their broad leaves falling gracefully to land in begrimed fountains. Naked children darted this way and that, their backs burning, to sup at the spigot or – to Joseph’s revulsion – scoop warm brown fountain-water into their mouths in handfuls. Laundry dangled from each iron-wrought balcony; flowers bloomed from each window-box. All the square was favoured with the dappled dance of sunlight filtering through the listless leaves. A gaggle of young paysannes chattered over one another nearby, erupting into waves of hilarity when Joseph murmured to Arnaud in English.

There was mourning in his friend’s eyes, despite his peaceful countenance; for all was smooth, but so much was at once ragged. Footprints sang out on slate and stone surfaces as they were forced to squint from the sun bouncing off a hundred porously creamy buildings. Yet there was a grime beneath the fingernails of the town which couldn’t quite be forgotten; there was pain in the bronzed faces which met theirs. There were distinguished old men in impeccable suits who sipped at their coffee in silence, and children folded away in street corners, their limbs fit to snap, their skin withered and jaundiced. There were ladies in white dresses who promenaded arm-in-arm, glancing bashfully at every man they passed – and lipsticked women with their breasts half-exposed, prowling the side-streets which Arnaud wouldn’t look down. There were houses, shops, businesses up for sale and others which were aging poorly, the paint flaking from their worn shutters and sills like dead skin.

It was only when Joseph caught sight of a pathetic scrap of paper, a rag on one of the walls, dirtied with dust and faded with age, which bore the ancient, baleful legend, ‘Je cherche mon mari’, that he pieced together the battle-scars of the town. Uzès, he saw, like countless other towns in France, was still warring with the infection Britain was doing her best to forget, which had cursed his birth and Arnaud’s with its foul taint and plunged all Europe into unending grief when they were far too young to understand what had been lost. Of course, this could not be voiced; and so, like Arnaud, Joseph turned his face from the darkness lurking in his peripheral vision, and only smiled. “It’s just so beautiful.”

Arnaud slowed as they approached a dark shop whose lettering was in the process of fading from a brassy gold to a peculiar green colour. Cobwebs caught the sunlight in the hollows of the undertaker’s window-frames, and dust lined every surface. The thought of the proceedings therein turned Joseph’s stomach, so he inclined to wait outside while Arnaud stopped in to speak with M. Fournier. The blood beat loudly in his temples as he turned his back to the sordid little shop – and his thoughts away from dead things.∎

Words by Annie King. Art by Ng Wei Kai.