Tapioca Age

My grandfather was born in Malaya, a first-generation ethnic Chinese immigrant. Gong-gong’s temperament – quiet and minimalist – fits a man of his humble background, but his eagerness for adventure is exceptional. His extensive travels grant him a remarkably inquisitive palate that is rare among the older generation. Prompted by my curiosity, I once asked my father if there was anything Gong-gong didn’t like to eat. “Tapioca.”

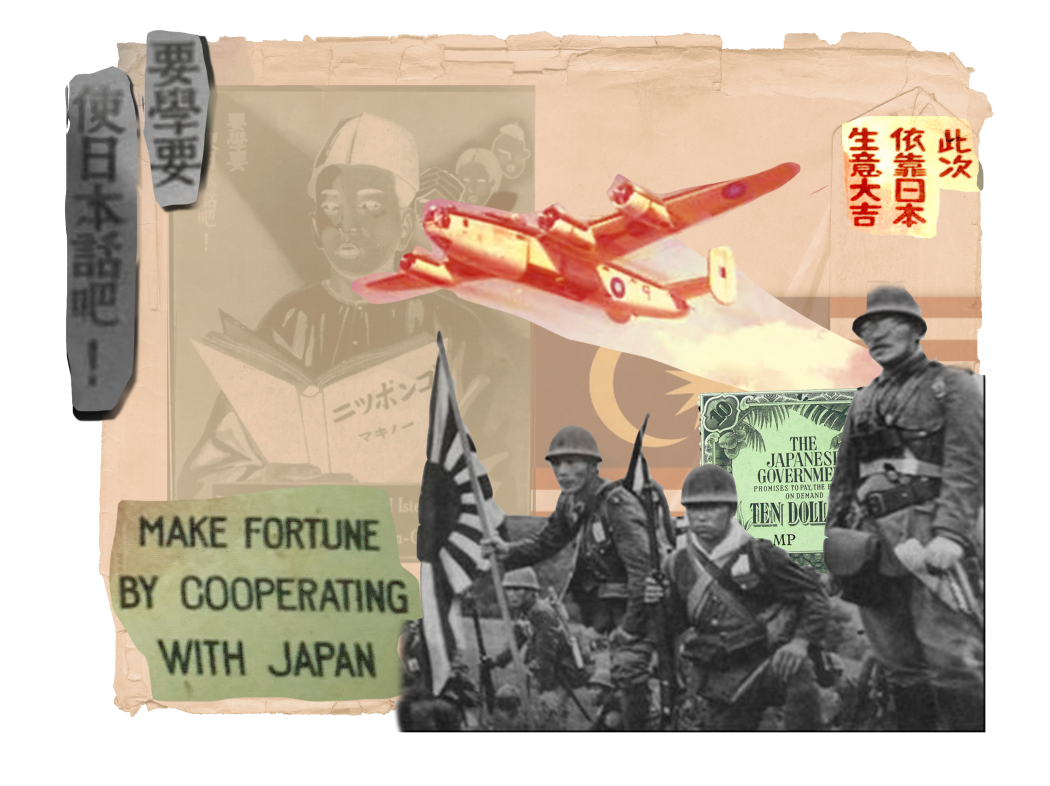

Gong-gong grew up amidst a complex series of events inaugurating Japan’s entry into World War Two. Japan’s Asian campaigns are often overshadowed by the attack on Pearl Harbour in the eyes of a Western-centric world, but the plan was ambitious: establish a vast empire covering most of East and Southeast Asia. They would be treading into territory long dominated by European imperialist powers that had no place in the new regional order.

On 8 December 1941, Japanese troops landed on the shores of Kota Bharu in northern Malaya. Thus, began an advance down south, marking the beginning of a dark epoch. Japanese troops quashed British resistance as they speedily traversed through Malaya’s heartlands on bicycles. By 31 January 1942, the whole of Malaya had fallen to the Japanese. In just under three months, they ended over a century of British rule. Though outnumbered, Japanese troops were mentally conditioned to die for the glory of their empire, whilst the British had their share of problems to deal with back home.

Locals differed on what to make of this new arrival. Chinese immigrants, rightfully afraid, were only too aware of the entrenched Sino-Japanese antagonism. Gong-gong had heard tales of the beheadings and rape which China had suffered. To some radical Malays, Japan embodied a bold resistance to the West. Malaya had been under the yoke of British rule for over a century, fostering a nascent nationalism that Japan exploited in propaganda campaigns. ”Asia for Asians”, they promised. Malaya was no stranger to the empty promises of a foreign power; betrayal and broken treaties had secured the Portuguese, Dutch, and British their nearly half-century-long presence on the peninsula. But the prospect of independence proved irresistible, luring nationalists to fight alongside their supposed liberators.

Malaya’s heterogeneous society of Malays, Chinese, and Indians would have different experiences of the occupation due to Japan’s animosity towards the Chinese. The Sook Ching, a cleansing campaign to eliminate perceived threats, was a manifestation of this antipathy. One by one, ethnic Chinese were screened for anti-Japanese elements by either officers or hooded informers. Massacres were seldom officially reported, but death estimates range in the tens of thousands.

The mass killing eventually stopped. Japan had an empire to build and moved to prioritise the cultural integration of their subjects. Gong-gong survived and considered himself lucky for it. The Japanese occupation brought about a new hell for Malaya, transforming daily life as the Japanese introduced measures to cement their pervasive influence on Malayan society, with education treated as a crucial avenue in building a loyal generation. Schools were taught in Japanese and followed a Japanese curriculum. Rice, so integral to the local diet, was strictly rationed. The bulk went to feed the Imperial Army, with the local population fed on scraps. Students were rewarded for undertaking a Japanese education with additional food supplies, but most locals practiced self-sufficiency by planting easy crops like tapioca and sweet potatoes in order to avoid starvation. Gong-gong didn’t go to school. After a youth spent living off tapioca, it’s not surprising that he now can’t stomach it.

Japanese military police, the Kempeitai, oversaw the enforcement of law and order. During their frequent house visits, Gong-gong and his family would hide in bushes to escape the regular beatings and stabbings. The Kempeitai routinely inflicted barbaric torture on civilians in order to extract information on anti-Japanese activity. A particularly cruel example, ‘Tokyo wine’ involved water being pumped into a subject’s mouth. Interrogators would then stomp on the subject’s bloated abdomen, forcing the water out through their orifices. Meanwhile, young women were forcibly taken from their communities to serve as sex slaves, euphemised to this day as ‘comfort women’. They were confined to their own rooms and faced rape up to 60 times a day. Most did not survive their time, and those who did endured severe sexual trauma.

Malaya’s experience of the Japanese occupation is by no means an anomaly. Atrocities defined the abominable period of history, shared across nations that fell under Japanese rule. The true extent of Japan’s impact in East and Southeast Asia deserves attention for the permanent mark left on the lives of people who lived through it. Mainstream history in Western countries has not afforded Japan’s war crimes a similar amount of attention as it has to Nazi Germany’s, easing the pressure on Japan to examine its past. Malaya’s unconventional recovery from these imperial wounds also failed to involve the retrospection thought essential for reconciliation.

Instead of holding on to grievances of events fresh in their memory, newly independent Malaysia moved on with remarkable speed. Poor, vulnerable, but finally free, a profound sense of excitement for self-determination and prosperity took precedence over demands for justice. Japan, thriving in its post-war economic miracle, presented an opportunity for a valuable source of investment into Malaysia’s industrialising economy.

The coming decades saw Japanese capital pouring in, helping stimulate the country’s subsequent economic development. The now familiar signs of Japanese influence slowly made their way into Malaysia’s culture. Malaysians showed a liking for these innovations and the nation which developed them. Politicians consciously cultivated good relations to continue driving growth, as when Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed endorsed a Look-East policy calling for the emulation of the Japanese work ethic and management style. These official sanctions by the government further solidified an admiration of Japan among Malaysians. No longer were they murderers and rapists. Japan is now viewed as an ally, a contributor to the nation’s higher standards of living, and a society of extraordinarily civilised people.

Flipping through the pages of the history textbook as a young Malaysian, an undeniable tension occupied my mind. It is hard to reconcile our history with the current reverence we have for Japan. Anger somehow felt trivial, directed towards horrific events that were quite detached from the present. I didn’t live through the occupation. I live without fear of persecution, privileged enough to enjoy the many comforts Japanese capital has brought to my country. Even Gong-gong likes Japanese things as much as anyone else.

To those who lived through the 1940s, forgiveness wasn’t a choice. The state had already granted it on their behalf, effectively shutting off hopes of reconciliation. They contented themselves with enjoying the material benefits of economic development. The older generation don’t hold explicit grievances towards the Japanese and rarely talk about their experiences during the occupation. It’s hard to tell whether the wounds have healed. Perhaps the decades seeing Japan in a positive light made up for the brief period of hell. Asian culture revolves around a ‘show, don’t tell’ principle. Outright expressions of remorse are hard to come by, and apologies are often presented in a material form instead. To the older generation who are most familiar with these norms, maybe Japan’s help in lifting the nation’s standard of living symbolises a genuine apology. Perhaps, true to their emotionally closed off selves, they’ve managed to bury those ill feelings – still very much alive – and got themselves in line with a society that cannot see the Japanese the way they do.

Malaysia’s experience in moving on from the occupation was set amidst a major imbalance of power between the two nations. The government chose to swallow their pride and reap the economic benefits of strong relations with their former tyrants. The power imbalances a nation faces appear to affect how strained relations are repaired post-conflict. Japan got off easy because of what they could offer. They weren’t forced to confront their past in a way conventionally expected of perpetrators of war crimes. Their investments didn’t reflect pure remorse but allowed them to extensively reach a booming market as a bonus. In comparison, survivors of the occupation had to suppress their intense anger and come to terms with the fact that the iniquities they faced might never be resolved. For a while, South Korean society looked to have moved on from decades of Japanese imperialism in exchange for economic support. However, long-suppressed animosity seems to have recently manifested after South Korea achieved its own growth miracle. No longer restrained by an unfavourable position, young South Koreans are taking on the grievances of those subjected to Japan’s atrocities.

It feels wrong to attribute the status quo to Japan’s efforts. Japanese aid was valuable, but the true burden of moving on was borne by the Malaysians who lived through the 1940s. They didn’t deserve that emotional labour but took it on anyway. Is moving on comparable to a reconciliation between the two countries? Maybe Malaysia has been lying to itself and will one day attain a renewed consciousness of history as South Korea has. This possibility of a resurgence in anti-Japanese sentiment seems unlikely. Though Malaysia is now less dependent on Japan, there is little to be gained from revisiting old wounds. Moving on from the past traumas inflicted by Japan and Britain allowed Malaysia to achieve a sense of mutual respect with its old oppressors, affirming for people that the colonial subjugation of the past will not be repeated. However, Malaysia’s progress in looking past its history was the result of its own effort. Our experiences cannot absolve Japan’s responsibility to ultimately confront its complicated history. ■

Words by Gee Ren Chee. Art by Eloise Fabre.