Observances

by Kate Greenberg | January 8, 2021

I was staring at the spidery print and into the fresh whiteness of my copy of Beowulf one Friday evening last September, while far away and unbeknownst to me, tales older and stranger had begun to sprawl inside my phone. A reticent but attentive member of an English freshers’ Facebook group, I scrolled, a day later, through a conversation gone sour. In response to some innocent query of everyone’s favourite novel, I saw that someone had ventured ‘Mein Kampf’. There followed then silences and words of showers which I didn’t understand, and then, further, much deeper down, came the leak of an ancient sadness which I didn’t know how to pronounce.

In advance of leaving for university, like many of my Jewish peers, I had been given fair warning about atmospheres going awry, had been lent advice about how to know how hard I should bite my tongue. The 2019 election approaching, a general disquiet in the Jewish community sat more loudly and stewed more deeply. In those months and moments it was like gathering spare buckets from the back of the shed, watching fundamental details drip through cracks on high. In the bigger picture, in other rooms and parts of the country, those cracks and tears might have been invisible: rustlings of the wind, of coins, the clamour of business as usual. But for the overwhelming majority of Jewish people, signs and smoke and damp ceilings were very, very difficult to pass under.

But measurements must be taken, distinctions must be made. There remains a certain kind of discrimination which Jewishness holds dear; which embraces all the laws and melodies and customs passed down from generation to generation in order, to some degree, to be separate. These things fall and have always fallen; the curl on the corner of the forehead, the silence and the knees during prayer, the seafood platter without the shellfish, the soft and loose pages of my grandfather’s siddur.

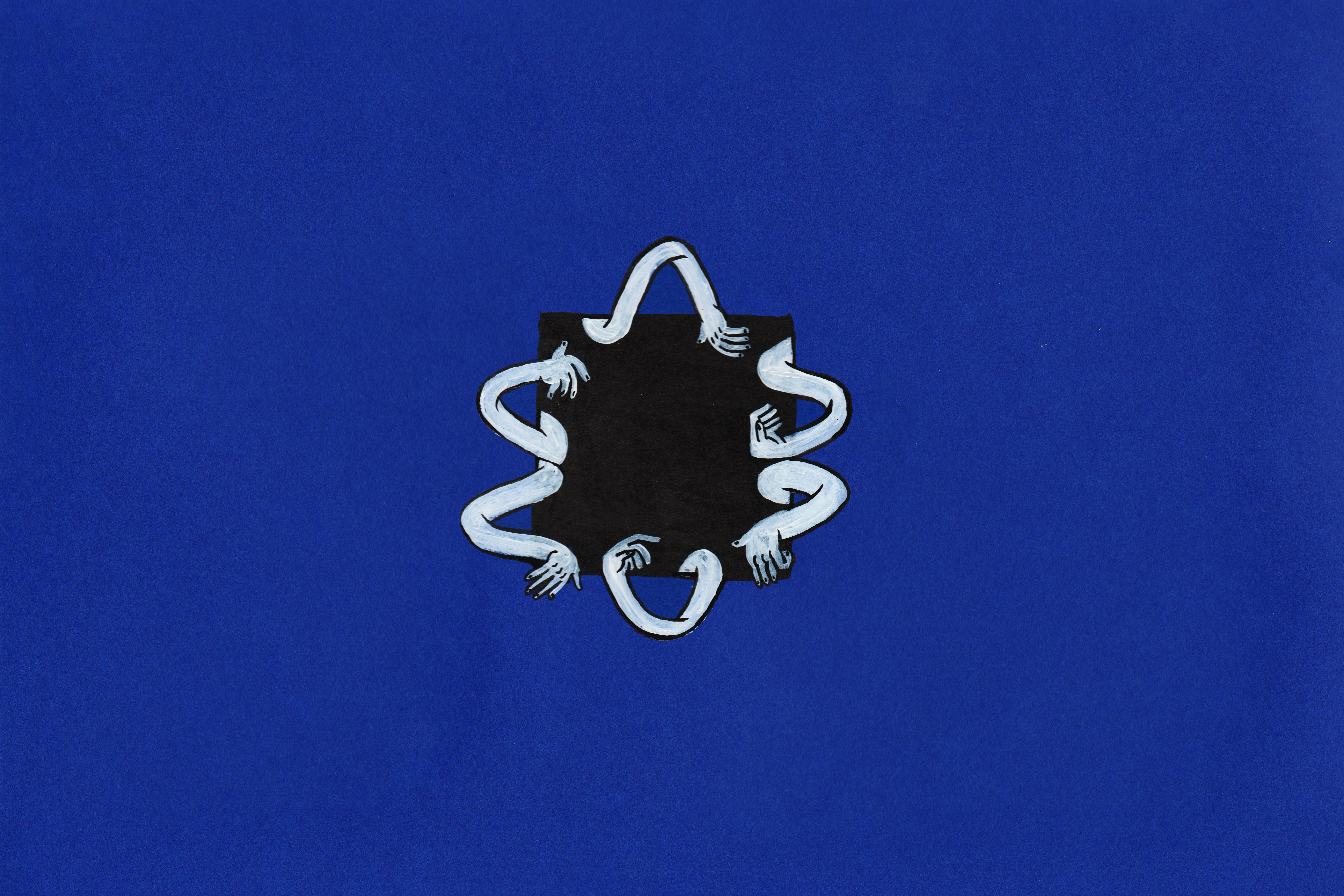

But I turn them with my own hands now, and through so many fine shades and shelves of difference, through so many different depths of desire to draw them. It is but a footstep, but a plummet from clause to clause. In disbelief I have tripped over swastikas on pavements, have raised my hand to my mouth at the long blast into the ram’s horn. I love Israel with a love that is lost inside and found apart from myself. I stand with the Palestinian people and carry their tragedy in the corner of my star of David that is always getting tangled around my neck. I do not always know what to say, or if I am expected to say something, or if I have said too much, at the wrong table and at the wrong time. I have forgotten what some words mean in Hebrew, but have learnt new ones in Yiddish.

I have ruined my eyesight straining to connect worlds, trying to get the accent just right. But I can still figure out human faces, continue to trip and trust across so many caveats, so many cushions. I have missed out on countless opportunities which have fallen on a Saturday, or a Shabbat, that heaviest and most precious piece of furniture. On the third day of freshers’ week, with some happy solemnness I did not participate in any planned events or go out and meet new people: it was Yom Kippur. I fasted, prayed, and played board games I’d brought from home with friends from home whom I’d never met before. I used to know the rules off by heart, but now I would say it is more by ear. I have spent long mornings tweaking emails apologising for the inconvenience and pointing to the moon, have broken my words, have regathered them in a different order, have fallen asleep over the pages of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle late in bed. It went over my head when I bought it, translated and removed, but still sometimes, and since memory, I stare at ceilings, thinking about names and names and other names, hills of unbuckled shoes. Those faraway and morbid lands lie under so many carpets, in so many dusty corners. They have always been there and I have always known them. Perhaps enough time has passed for things to be turned on their head, but I find I am still looking over my shoulder, through loopholes, inside wrinkles, holding onto some last length of railing, holding out for faces I’ve only ever heard of.

That Yom Kippur, there were words of a shooting in a German synagogue, thoughts of ambulances faraway, a hum which stayed and stayed inside our throats. This I write a year later in the flurry of a long Shabbat afternoon, with a brick of guilt balanced on my chest, unable to wait for the sun to set. This is just a turning down of some angry noise, some twittering and pecking that has gone on too long. This is just a paying up of sorrows with what I happened to have in my pocket.

And some things are not up for sale. It must be said that white Jewish people are privileged today, and do not suffer the ongoing reality of systemic racism as Black people do. There is no exchange rate here. Today we have space, whole suburbs, to breathe in; we do not live in fear of being stopped and strangled by the police. We can hide our Jewishness in the attic, when we need to. But when may we need to? I fear there must be and long has been some assumption – that all Jews are white – as well as some sub clause – that the whiteness of white Jews comes with strings attached. Tones and pages have been turned with terrifying grace, people have been turned into goats, been herded in by the hundred to warm consciences and whiten Christmases. Lately, I have seen photographs of cattle-cars and long queues far away, and well up with thoughts of full circles. I sit buried in my sofa, and only saddle upright to hope against old sentences being replayed, new silences being respected, more museums made.

Saturdays aren’t so special now; now the falling of snow a miracle; winters now like springs. But there is something in the air, something else which I wear on my sleeve. My oldest book sleeps by my bed, waiting for me to want it all to come flooding back, the frills and the warts and all the words. I kiss the covers when I close them, and sometimes that is all that I have done. Once, crossing the main road on a Friday evening, holding onto it, a man shot his head out the window to yell at us, us fucking Yids. I held it so hard then, I dug it into my ribs, and then afterwards, sitting in synagogue, I squinted at the letters of gold and the yellow pages which touched my cold and mottled palms, trying to see what he caught sight of, trying to make out something in the angles and between the lines. There settled drops of water, rivers of ebony twigs and ivory bones, filled with every slight look and syllable for which I have tried to find an answer, have tried to find a different home. ■

Words by Kate Greenberg. Art by Bee Eveleigh-Evans.