“It could be the next Tiananmen Square”

by Poppy Sowerby | June 22, 2019

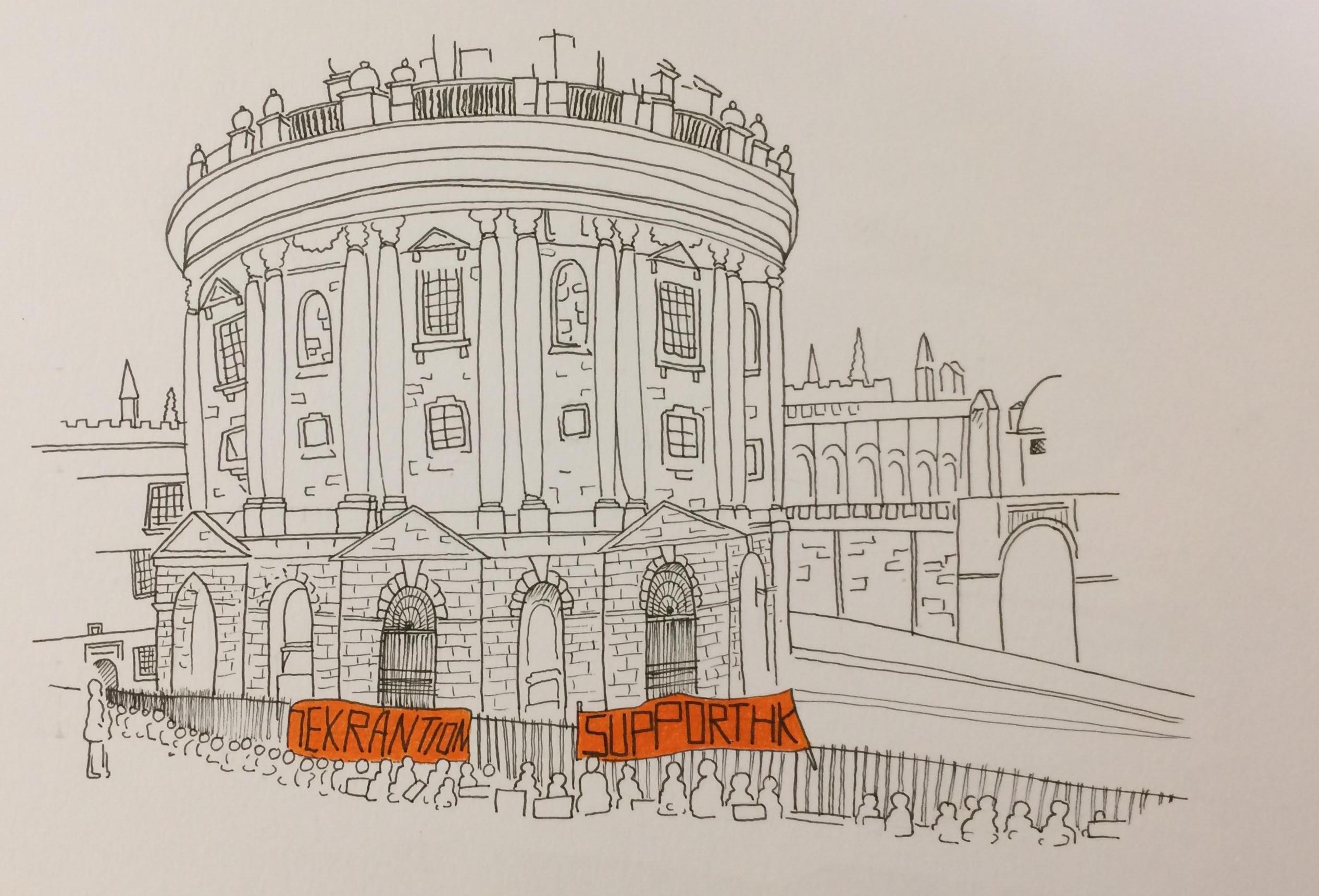

Last Thursday, a throng of students and staff gathered outside the Rad Cam to protest the proposed Extradition Law Amendment Bill in Hong Kong. It’s a silent protest, reflecting the pacifism of the activists these people follow closely in the press. Still, quiet conversations patter beneath umbrellas along the iron railings of the Bodleian. It’s a strange atmosphere: sitting on the cobbles with banners and leaflets limp from the rain, their hush is broken here and there by finalists cheering in Exeter and Brasenose, by others shrieking as they dash through the cold from the library.

It’s strange for other reasons, too. Mainly because this is Oxford, where protests are held almost weekly with no rubber bullets, no teargas, and no fear of consequences from the authorities, should protesters be identified. These are not the conditions today. The risk associated with this quiet, rainy protest is unlike anything Oxford usually sees – in Hong Kong itself, peaceful activists have been subject to police brutality, imprisoned and marked by the government, endangering their jobs and families. Among the protesters is Dr Anders Corr, an independent analyst who has worked in US military intelligence, including nuclear weapons and border security. Now, his analytics company provides political risk analysis to commercial, non-profit and media clients, and he refers to complexities of the political predicament of Hong Kong that I initially find surprising. As the numbers of students grow, Dr Corr is clearly impressed by the courage of the scene.

“The CCP infiltrates everything,” he tells me. “I saw one guy I know who was from mainland China, and he wasn’t in the group; he didn’t get his picture taken, but even to show up on the side-lines is brave.” At half past six, they crystallise: a band forms outside the dome, photos are taken. People wear pollution masks to obscure their faces but thrust their banners into lenses. Passers-by watch, pausing in the cold to read the placards. As the organisers are talking, Dr Corr adds that there “may be people here taking pictures from the Communist Party”. There is more at stake for these students than I thought.

Events in Hong Kong are constantly developing and have moved on even since this Thursday night gathering, but the background of this wave of turmoil is both long-term and complex. It was Thatcher and Premier Zhao Ziyang who presided over the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, in which Britain handed over Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China. The PRC gave a guarantee that Hong Kong’s legal system and way of life would be unchanged and uninfluenced by China for fifty years, from 1997. There have been infringements on this treaty ever since, culminating in the 2014 Umbrella Movement, which in many ways set the tone for these current protests. During a 79-day occupation seeking more transparent elections, protesters responded to police use of pepper spray by using umbrellas, quickly resulting in a symbolic image of passive resistance. The movement – of which many former leaders have recently been imprisoned – attracted international attention for its pacifism and predominantly young demographic. June has seen days of protesting in Hong Kong itself as a result of the proposal of the Extradition Bill. This controversial law would allow the country to deport criminals with a prison term of more than seven years to China. Part of the difficulty is the slipperiness and uncertainty of the bill: as one protester asks, “what even is a crime that would entail seven years? It hasn’t been very clearly applied in legal terms in China, so they can apply those ambiguous boundaries to Hong Kong”. Suspicion of governmental motives and the creep of corruption into the public sphere seems not so far from home.

The governmental response to the protests in Hong Kong has been confusing and hypocritical, something many protesters wryly connect with domestic politics in the West. Those I speak to have much to say about Carrie Lam, Chief Executive since 2017 and a central Chinese-backed figure both spearheading the bill, and orchestrating police response to the demonstrations. Two students here point to a recent interview in which Lam referred to herself as “like a mother” to Hong Kong, using her two sons as an analogy for her personal attachment to the country. In spite of this motherly attachment, activists have been subject to shocking police brutality. One post-grad questions, “if she really cares about her sons like the Hong Kong young people, why did she use so much force to crack down on the protests?” Two other students claim that “both of her children have foreign passports”, along with “most Hong Kong officials and policemen”. Lam has defended the bill by arguing that without it, Hong Kong would risk “becoming a haven for fugitives”, a phrase that is unfailingly met with eye-rolls as I quote it. One student puts it simply: “it’s not like Hong Kong doesn’t have its own legal system”. Over the evening, the Chief Executive emerges as a sort of broken Theresa May figure: some feel sorry for her (“it’s a terrible job to do”), some doubt her legitimacy (“she was not elected by a majority”); most agree that her leadership puts the independence and the national identity of Hong Kong at risk.

And it is an identity, a quickly-faltering freedom, that these people are here to defend. One student who has lived in Hong Kong all her life tells me “the brutality is really scary for me to see, somewhere that’s so safe. I feel so much safer walking out at night in Hong Kong than here.” For many here, Hong Kong’s identity is wedded to regular and tolerated protests, safe streets, and a sense of independence. The violence of police retaliation and the profound consequences of state control in this distant and complex conflict can sometimes seem difficult to conceive of in an environment of privilege and relative stability. But for many people here, the attachment is emotional. One man remembers a different Hong Kong: “people have had their freedom taken away gradually, bit-by-bit, and it’s not easy to take when it’s something you used to have. When you see the news it feels very heavy. It’s deeper than that.”

For other protesters, it is the spirit of solidarity that draws them to these damp cobbles. When I ask them why they’re here, there’s a collective response: not for themselves, but for the people of Hong Kong, and for the general defence of freedom. I notice the protests are student-heavy and compare them to the similar makeup of those abroad: one man responds emphatically that “one day students will be in positions of power”, another insists that “it’s going to light a spark”. I ask them what impact this evening will have: Michael Rowand, a post-grad within the huddle, tells me “even if you can’t be a leader in a protest movement, you can be a good follower and do what you can, so I’m choosing to do that. I think those people [protesting in Hong Kong] are heroes, so how can we not come out here and sit through a little bit of rain and stand with them?”

After an hour in the drizzle, the organisers thank everyone. They peel off into the warm. The protest has gone well, with a high turnout despite the weather. The Rad Cam looms behind the group in the photographs, a reminder of the symbolic support this university can lend to movements that need it, and the strangely familiar context of this international protest. The turmoil in Hong Kong rumbles on: Dr Corr suggests it could amount to “the next Tiananmen Square” if Chinese influence on the country continues to creep in. I ask the protesters what they think will happen next: nobody knows. What is clear is the risk and courage of many among these hundred or so people, who may well have feared identification.

Student protest is alive and well in Oxford, and is critical at a time where political events here and abroad become more febrile, and increasingly beset by the distortions of social media. This evening has been a success, but the strangeness of cause and context reflects more widely on demonstrations held at this university. Here, a political reality involving blood and bullets is paired with a dome that stands in for the entire reputation of Oxford, printed in gloss on thousands of postcards. The power of protest here relies on that reputation, the inference that if there is support in Oxford, there is support in general. A post-grad tells me a recent India-Pakistan protest against activities in Kashmir made headlines in those countries; he hopes the same will happen here. There’s a strange continuity between these students peering through the rain in a famous stone square and the tourists filtering through the souvenir shops a few streets away. In each case, the image of Oxford is a monolith, an idea. Beneath it all, there are shadowy complexities that won’t make the headlines. There won’t be a counter-protest here, but these students know many others who support the Chinese Communist Party, and who wonder why Hong Kong residents can’t simply “trust the government”, as one man puts it.

On Tuesday, the Guardian reported that Oxford will receive the biggest single donation “since the Renaissance”, a £150 million gift from the American Stephen Schwarzman. Dr Corr informs me that Schwarzman is “deeply embedded in pro-China networks”. Perhaps this demonstration will emblazon papers tomorrow, but the layers of influence in this historic conflict rumble beneath this scene on the cobbles: the actual impact Oxford will have in Hong Kong lies in the quiet machinery of our financial manoeuvrings, and in the noticeable absence of pro-extradition groups. The feeling of the evening is clear. The ink will soon dry on the masked faces of these careful students, but networks of power appear to spread beyond us. Despite this, the role of student protest is enduring: to drag these complexities out into the open, and to catalyse a response. The protest has ended, and the violence of protests on the 12th June saw Carrie Lam forced to suspend the bill indefinitely. Yet the objectives of this movement ring out in all demonstrations here, in the next groups that will cluster around these railings. Underpinning it all is the hope that placards in the rain can in fact create dialogues with large systems, systems that need to hear us.∎

Words by Poppy Sowerby. Illustration by Eve Robson-Rooney.