China’s Third Way

by Barney Pite | November 16, 2019

Shenzhen, the fourth largest city on the Chinese mainland, and one of the largest cities in the world, is contemporary China at its most bizarre and contradictory. Straddling the border with Hong Kong, and part of the broader geographic and economic region known as the Pearl River Delta, Shenzhen is the centre of the Chinese high-tech industry and a city of futuristic high-rises, a surgically clean underground system, and an affluent, ambitious middle class. But between the bank headquarters, tech unicorns, and insurance companies, Shenzhen is a city under a nominally communist government, despite all the bells and whistles of a market capitalist system.

I realised this one-day last summer, as I sat on the subway in the Chinese city of Shenzhen. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a tiny hammer and sickle in the corner of the electronic display board opposite me. The screen was playing a political advertisement produced by the Chinese Communist Party. I didn’t understand all of it, but the subtext was clear: loyalty to the nation and submission to the party. I was confused by the tiny symbol. It seemed out of place.

This dissonance addresses something crucial about contemporary China. China does not play by the ideological rules which the West uses to categorize the world. Western political formulations depend on the validity of Western narratives, but China has its own past to answer to, and three thousand years of it. China is communist in name and capitalist in nature, but in truth, it is neither of those things.

Shenzhen’s taxis are electric. The air and streets are clean. There are carefully landscaped public parks with basketball courts and football pitches, mountains you can hike in, an inexpensive and well-maintained subway system, and countless electronics stores and ice-tea parlours. Shenzhen is a fun place to spend a few days, closer to the Western perception of Singapore than Shanghai or Beijing. And yet public transportation (used by Shenzhen’s bankers, engineers, start-up innovators, and disruptors) carries authoritarian iconography – iconography representing the immense and omnipresent Chinese state.

This contrast runs deep in modern China. Despite its name, the Chinese Communist Party hasn’t pursued defensibly communist policies since the 1980s, when China, under the premiership of Deng Xiaoping, first began to modernise. Shenzhen’s largest corporations – Tencent, a conglomerate centred around social media and gaming, BYD, which sells electric cars, and Huawei, the mobile phone manufacturer with nigh on 20% of the global market share – are all privately owned corporations. But Huawei has been described as both state-owned and private, depending, for a large part, upon the circumstances of its description. There is an ongoing and contentious debate surrounding the extent to which the Chinese government influences Huawei’s corporate affairs. Some argue that China uses the company as a vehicle for its geopolitical goals. In this way, as in so many others, China should perplex us; it eludes our traditional ideas of political and commercial categorisation. The more we hunt for clarity, the more it evades us.

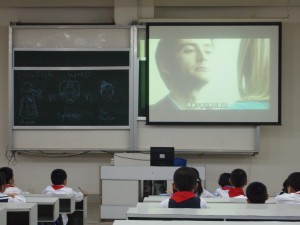

China offers us fierce traditions in the midst of overwhelming change, a chairman who promises a freer market but a stronger party, and a communist government staffed by tech moguls and entrepreneurs. How can outsiders make sense of this? How can a country reconcile these oppositions? How can it nurture and support an economy based upon the principles of market capitalism, but adorn its schools and public transportation with the hammer and sickle? The answer, in the case of Shenzhen, is the distinctive and unusual way that China walks a tightrope between these separate systems: Shenzhen is a Special Economic Zone, or an SEZ, a designation first used in 1979 to allow coastal areas of the Chinese mainland to open themselves up to trade and investment from the West. The Special Economic Zones, which now number 20, are characterised by free-trade, economic freedom from the centralised government, and their co-operation with and utilisation of foreign capital sources. They, and Shenzhen particularly, have been unbelievably successful. Shenzhen has gone from a fishing village of 30,000 residents in the 1970s, to a mega-city of eleven million, and, in 2017, grew its GDP by 8.8% to $338 billion, roughly the same size as Hong Kong or Singapore. All of that from nearly nothing.

It’s remarkable that a city as huge as Shenzhen could rise from nothing in so short a time; that everything, from roads to bridges to train stations, could all just appear where there was nothing 20 years before. And this growth will continue. In August of 2019, China released a document outlining how Shenzhen will transform to demonstrate ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics.’ China is like this – it is a country which moves more quickly and with more ferocious purpose than almost anywhere else. Where else, save perhaps the nations of the oil-rich Gulf, could simply decide that a minor border town was to become one of the world’s most innovative mega-cities, and then deliver on that plan?

All of this growth, both demographic and economic, is down to the distinctly Chinese third way, down to the path between centrally planned economic policy and market freedom to innovate and disrupt. China has always had a history of state power. Between the time of the Tang Dynasty and 1905, the greatest honour for a young Chinese citizen was to pass the Chinese civil service examination and take a roll in the huge imperial bureaucracy – so great was the culture’s focus on enlightened centralised governance.

Even today, China doesn’t ever let you forget the authority of its centralised government. After you buy a ticket to ride the underground, you have to go through a full body scanner and have your bags x-rayed. Stern-looking police officers stare you down at road crossings. There are cameras everywhere – on the streets, in the markets, on the underground, and it’s impossible to access Facebook, Google, or YouTube without a VPN.

Centralised Chinese power extends further. Sinopec, the world’s largest oil company, is state-owned, as are China’s grid, airlines, and telecommunications companies. Yet China is home to three of the largest stock exchanges in the world and some of the most innovative technological enterprises anywhere, and most of it in private rather than governmental ownership. In a country not known for its car companies, China sells some of the most reliable electric cars on the planet through BYD, EV manufacturer part-owned by American mega-investor Warren Buffett, despite the constrictions of the trade war. China’s economy – in much the same way as its political system – strikes a fragile balance between public and private, but it also constructs newer, more relevant categories. For better or for worse, it makes its own rules.

China’s willingness to consciously and deliberately transcend Western political designations – to integrate the best of market capitalist systems with schemes of economic planning – is res. Shenzhen is convincing and confident – the buildings are mesmerising, the infrastructure futuristic, the skyscrapers reach ever higher into the clouds.

It has been 70 years since the foundation of the PRC, and it is impossible not to wonder how radically and fundamentally it will have changed in the next 20 years. And China, like every country and every empire, contains contradictory multitudes. It straddles the boundaries of ancient and modern, of prosperity and corruption – and, crucially, of capitalist and communist economic and political models, but it also disrupts and confounds those very categories. China’s fusion of various, potentially conflicting political forms reminds us that China has never been a country which plays by Western rules or fits into Western categories – it represents another twist in the path and another bend in the road. China predates Marx, Keynes, Adam Smith, and Milton Friedman by some three thousand years; it has every right to throw their anachronistic categories to the wind and make to make its own way. We must confront the ideological realities of Chinese hegemony and the challenge it poses to established political categories, and we must confront a world with the hammer-and-sickle, albeit one with an altered, elusive, new meaning – resurgent. We cannot rely on old categories. The world has outgrown them. ∎

Words by Barney Pite. Artwork by Wikicommons.