Memories of a teen soldier

by David Saveliev, Yaroslav Amirkhanov | August 15, 2019

The Situation

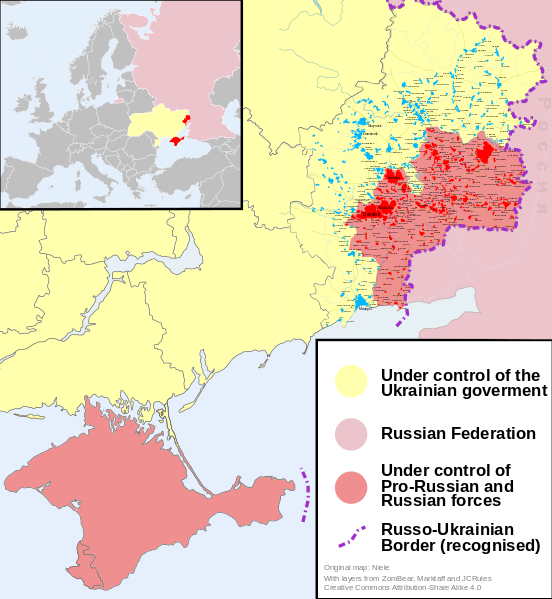

Ukraine has always been a battleground between the East and the West. In 2014, in a new spiral of the centuries-old geopolitical gamble, Russia annexed the strategically vital Crimean peninsula from Ukraine. It did so after the leaders of the pro-western Revolution of Dignity overthrew the old, pro-Russian Ukrainian government. Fearful for its sphere of influence in Eastern Europe, Russia also began funding separatists in the majority-Russian eastern regions of Ukraine. The separatists clashed with unprepared Ukrainian military, beginning an ongoing war that killed thousands and displaced millions.

The Author

In the middle of this conflict were young people, ground away by the cogs of war. The three autobiographical short stories I am presenting to you are written by Yaroslav Amirkhanov.

He was an underage volunteer, fighting with the disorganised Ukrainian forces against the separatists and their Russian backers. He fought and killed at an age when young people in Britain begin their first year at University. Disenchanted with the war he came back with a medal for heroism, a great deal of scars and even more stories. He has written a book in Ukrainian that is yet to be published — three stories from that book are presented here.

Songs play a big role in his stories, as well as in Ukrainian culture. I highly recommend listening to the songs he mentions in the stories while reading — the links are in footnotes. Nowadays Amirkhanov study to be a doctor. He also works as an EMT in Ukraine. I hope you will find his stories as meaningful and sincere as I did.

The Translator & Illustrator

My name is David Saveliev. I am a Fourth Year International Relations student at Johns Hopkins University, studying abroad at the University of Oxford for the academic year of 2018-19.

I am an American with roots in the former Soviet Union. The East-West dichotomy in my family history has always fascinated me. Thus, in 2017, I embarked on a journey to the Ukrainian war zone to make a documentary film about the war’s impact on Ukrainians. A year later, one of my Ukrainian assistants introduced me to Yaroslav Amirkhanov and his book — that is how our partnership began.

Amirkhanov is a promising writer; and I hope I did justice to his unique style of storytelling.

Please enjoy.

The Date

Autumn meets me with an Indian summer. My breakfast —a pear from a military-issued backpack. I eat the whole fruit, swallow the sour stones. Satisfied, I throw the pear’s tail in my pocket. It will rest together with an old grenade ring — what fed me and what protected me.

I walk onto the Sumskaya street and, as I always do, begin to run.

My Walkman plays Spleen. The good old Lifeline[1].

The fires are burning, the stars are twinkling

All is hard and all is easy

We’re gone off to the outer space

There is nothing left to strive for in this world

I hear a jingling in my chest. My most important possessions: a silver crucifix and dog tags. My mother’s and my father’s faiths.

I look around me at the smiling teenagers. The longer I watch them, the more I wonder: “Why am I not smiling?”. My thoughts are interrupted by the humid air radiating off the Mirror Stream Fountain and then suddenly —a warm embrace.

She was waiting for me.

I hear her laughter, but feel her tears on my cheek.

She smells like an angel.

She looks right through the mirror of my eyes, into my soul.

I only say a little bit, because with her I don’t need to much.

— I love you.

It’s a pity I can’t say it in fewer words.

I catch the urge to take her to the church walls or under the Opera and Ballet Theater or somewhere else —to find cover, away from the open space.

I see myself in her eyes: stone faced, and in her hazel mirrors some frightened beast, which has forgotten how to love and be loved.

I didn’t come home from war.

It’s wasn’t me who came back.

Two zincs[2] full of words

Victory is not just a celebration. For the losers, everything is over.

For the winners, the work has just begun.

First, we need to search for the dead.

I’m crawling around a corpse on all fours. I’m not afraid of the boy anymore — the dead don’t bite. Only his youth makes my heart skip a beat: I doubt he’s even twenty. His rifle is loaded. He never got a chance to fire.

I can’t take my eyes off him: his skin is white, like calcium, his eyes are brown and teary.

Frightened eyes of a frightened child.

I stare at his face, but my hands continue to search his body. In the pectoral pocket – a piece of paper. Maybe something important.

A small sheet: about 9×12 cm. I skim through: will do I need to alert the sergeant? Not worth it. The letter wasn’t business: not a report, order or map.

It is handwritten. The hand was trembling, the letters are rounded, large. I read the paragraphs: “Dear Leyoshenka ..”, “When will you return? Is it over yet? There are no letters from you … “,” Why did they draft you? You never killed anyone … “,” Why don’t you answer the phone? .. “,” I dreamed of you yesterday … “,” I pray and cry every day… “

The letter is from a woman, a fiancé or wife? Probably a girlfriend — he’s too young, this Lesha.

I’ve got those too. Everyone here gets letters like this.

And still this one is different.

In the end the girl wrote a poem.

Something burns my insides — the letter is shot through at the end. The bottom of the paper is red, bloody. Dried blood. But I see enough of the first two lines of the last paragraph:

If it takes forever I will wait for you

For a thousand summers I will wait for you[3]

I press my sleeve to my face to dry my eyes as I check the return address.

Mechanically I shut the enemy’s eyes.

Victory.

But never a celebration.

Long, happy life

Silence. Not just a ceasefire, but silence. The dawn is quiet, and the red sun rising will be the bloodiest thing today.

And the sunset. Sunsets are always good because you can put another notch in your helmet.

It’s already been half a week, a few more and we will be sent home. On days like this you pray for the enemies to leave, to stop pouring fire on you. And you hope to not screw it up yourself.

I walk around my friends in our year-old camp. Throat is sore and dry. Slow steps. It’s about time I lose the habit of running.

The tiny room with a sink and bath isn’t empty, but there’s no space for shyness.

I scoop water out of washstand tank and drink it from a wounded cup. It’s missing a small triangle .

A bath is one of our few luxuries. If you bring enough water, you can feel like a king.

Jackpot[4] is splashing in the bath. The young man foams his hands with a bar of soap, and then rubs his hair and beard. We use soap for shampoo, shaving cream, and sometimes as an antiseptic.

He dives into the water and shakes his head. He looks like a bulldog, in this light he’s almost well-fed, his cheeks almost full.

I look at him with fascination. And then I notice a yellow bath duck. Jackpot found it somewhere, he plays with it every time he takes a bath.

— You know, there were some small ducklings, drawn on the package, where I found her. But she was alone, her daughters were lost. I am taking a bath with an inconsolable widow.

— How do you know that’s a female duck

— Well, look at those red lips! Oh, what a flirt she is.

I put the cup on a table, wipe my mouth with my sleeve. War tolerates a small disregard for etiquette.

I get up to leave chuckling:

— That’s a beak, you idiot.

I can hear Guiya[5] singing a lullaby on the street. The big man put almost all his money on his phone, he makes the same call to Georgia every evening despite the cost. He is humming in Georgian into the wheezing speaker.

A little rain rained over the big glade

It rained, it rained, it rained

Whoever insults us will get a knife in the heart

A knife, a knife, a knife[6]

I smile and wander down the corridor to my mattress, tapping the wall with my fingers. They are unusually clean and un-gloved, no dirt, or earth, no gunpowder under the nails. It’s strange to go around without my old gloves.

I think about not having to reach for them every morning.

Goethe and Hamlet are in the shared room. Goethe is whistling the Turkish March with a book of Weller, and Hamlet is unravelling his headphones. I see his phone with our group photo at a dinner, in a restaurant table laden with dishes. Choking on field rations later, thoughts of those days return constantly. Hamlet is already nostalgic, even though we are still together. We would never have met if not for the war.

Goethe looks up from his book and says:

— So I just looked at the map: why is the Azov a sea, while Greenland isn’t a continent?

— Dude, who cares besides you? — I ask with a smile. Despite his idiocy, my smile is sincere: no one except this eccentric boy would have had that thought. Always somehow distracted, sometimes entertaining, I’ll miss him.

— Look, it’s huge! Why is it the largest island, but not the smallest continent? Who decides what an island is? Who decided for the indigenous people of Greenland? Greenlanders have the right to self-determination. Let them hold a referendum!

— Enough referendums, let them decide peacefully.

— Well, what would they fight over? It’s a block of ice? It’s less populated than the polar caps.

Give a fool a reason to talk. Everyone is laughing. But I can’t let go, I look after them, like little children.

Do I sit down?

Should I relax?

I lean against the wall, listening to Goethe rambling, and Hamlet singing something almost soundlessly, with just his lips. Everything turns into a uniformed humming.

White noise for ears, ears too tired to stay sharp.

Suddenly the veil is torn: singing is tearing the pleura of the air. It’s a deep voice, untrained, and unsure, but with a shiver that makes it somehow convincing.

The merciless depths of wrinkles,

Mariana trenches of eyes

Martian Chronicles of us, us, us,

In the middle of idéntical walls

In the coffins on remote houses,

In the impenetrable icy silence

I know this song. But I do not know what will happen next. Hamlet is singing, he’s shouting at me, Goethe and everyone else as well. Nothing is certain except for the refrain:

Long happy life

Such a long happy life

From now on a long happy life

To each of us

To each of us

To each of us

Each of us [7]

A flimsy dam, once solid cement, is now a soaked handful of brushwood, crumbling inside me. Everything breaks loose.

My colleagues, my friends, my new sons are rushing to me:

— Why are you crying, Hedgehog? Come here.

[1] Lifeline is a cult Russian song from the 90s.

[2] Zincs — slang for both ammo boxes and soldiers’ coffins

[3] The young man’s girlfriend quotes the Connie Francis’ hit.

[4] Every soldier in the Ukrainian military has a call sign. Their purpose is twofold: they protect soldiers’ identities and make battle communication easier.

[5] Guiya is a Georgian volunteer. There are many Georgians fighting in the Ukrainians military. Georgia was invaded by Russia in 2008

[6] This is Danama, a traditional children’s lullaby from Georgia

[7] The eponymous Long, Happy Life is another cult classic — a punk song from the late Soviet Union. ∎

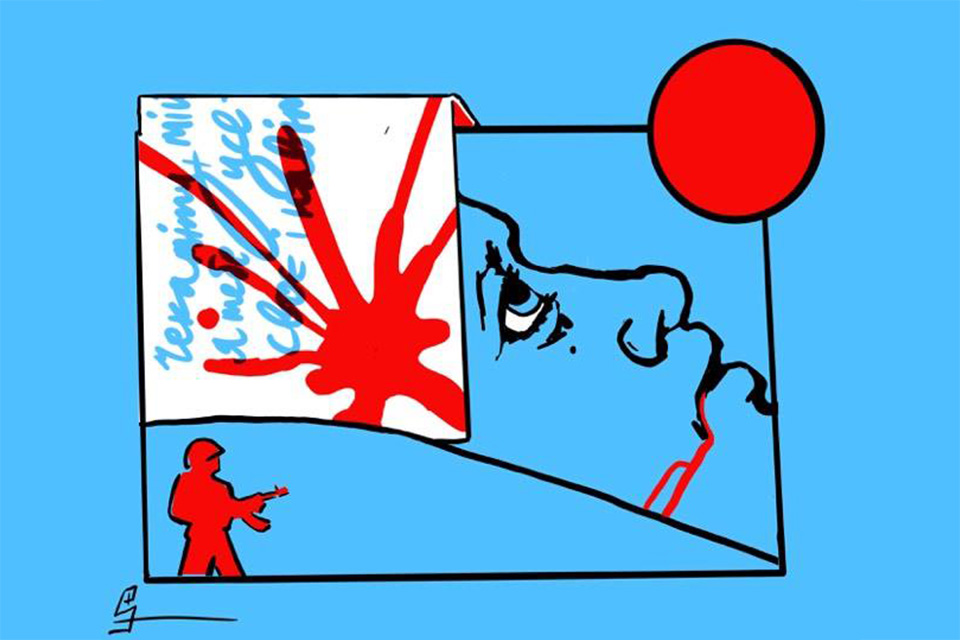

Words by Yaroslav Amirkhanov, translated by David Saveliev. Illustration by David Saveliev.