language/politics/identities in Eastern Europe’s breakaway territories

by Leo gadaski | March 1, 2019

After a lengthy interrogation by a Russian soldier, which included questions ranging from the etymology of my middle name to my dad’s job (but not, naturally, my mum’s), I was allowed to cross the border from Georgia into the sunny Republic of Abkhazia. The strange thing about this crossing, however; as the Home Office, the UN, and any other western government source will tell you – was that this border does not exist.

Abkhazia is one of a high number of so-called ‘frozen conflict zones’ – ‘breakaway states’ – in the former Soviet Union. Its independence is recognised by a rather motley bunch: Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Nauru, and Syria. This is, of course, excluding the other places like it: South Ossetia, Transnistria and Nagorno-Karabakh, which are generally considered to be parts of Georgia, Moldova, and Azerbaijan, do so, too. Soon after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the deterioration of centralised control from Moscow, violent separatist conflicts erupted in each of these places, most of which ended without official peace agreements. Independent governments retain de facto control with financial and military support from Russia, or, in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, from Armenia. Almost any man you encounter in the regions who was of fighting age at the time of the conflicts will have harrowing tales to tell. The dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh remains the most volatile of the three. It is strictly prohibited for tourists to travel anywhere near the ‘border’ with Azerbaijan. Soldiers patrolling this border – officially deep into Azeri territory – are occasionally picked off by snipers. The conflict is far from ‘frozen.’

My Russian was far more useful in Abkhazia than elsewhere in Georgia; for all you knew, it could have been a part of Russia. Although Russian seemed the predominant language, I would often hear another alongside it: Abkhaz, a language I had scarcely known of prior to my trip. In Abhkazia, Russian happens to be a co-official language, just like Belarussian in Belarus, Kazakh in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan. I had not overheard it nor found anyone who claimed to speak it, yet I was struck by the sight of Abkhaz on signs and official documents. Later, while travelling, I finally came face to face with a proud Abkhaz speaker, the monk Panteleimon Adzhinzhal. I took the opportunity to ask him how important this language was to the Abkhaz people:

“You know, I myself have many questions about the meaning and role of social communication in this country. There’s much that even I don’t understand. I almost always see no logic in the political declarations that make up official modern Abkhaz narrative. I can only notice that the vast majority of Abkhazians – both in the public sphere and in their close circles – believe with conviction that the Abkhaz language is extremely important. Of course, if you take an outsider’s point of view, that Abkhazia is a destroyed country which has still not fully recovered after 25 years, it’s hard to believe that the situation for true Abkhazians has nonetheless radically improved over this period.”

Here he is referring to the devastating separatist war of 1993 which led to Abkhazia’s quasi-independence. Atrocities were committed on both sides, most notably the ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia by pro-separatist troops. Much of the capital, Sukhumi, was destroyed during the conflict. Today, the shell of the abandoned parliament building remains standing in the centre of the city as a harrowing reminder of the all-too-recent horrors.

Panteleimon continued: “Ethnic Abkhazians have turned from a marginal community to the leading ethnic group in the territory, therefore they haven’t felt the destruction so keenly. The same goes for the language… The situation with the Abkhaz language has vastly improved over the last 25 years and continues to do so. Another question is to what extent this is necessary – to what extent is language a real priority in the Abkhaz question?”

This was exactly what I’d been wondering. Now I asked him whether he spoke Abkhaz and if he might be able to shed some light on the relations between Abkhaz-speakers and Russian-speakers within Abkhazia:

“We have a difficult relationship with Russian. When Georgia started to impose its language everywhere, it became clear that we’d only be able to survive using Russian. It’s said that there was even a moment during the Soviet era when Georgia decreed that in Abkhaz schools, all teaching should be done in Abkhaz… I’m not sure if you’re aware, but during the Soviet era students were only taught in Abkhaz schools until the age of ten. Therefore, Abkhaz language and literature were taught almost every day but the rest of the subjects were taught in Russian. Abkhazians refused to conduct all teaching in Abkhaz, as the graduates from these schools wouldn’t be able to continue their study in Russia, and they’d have to study in Georgia according to Soviet quotas. So Russian for us was not just a civilising language, but our saving grace.”

It is important to see Russian as an imperial language, like French and English. Russian opens up a huge wealth of cultural and economic opportunities that Georgian does not. This is particularly appealing to Abkhazians because the opportunities that the Abkhaz language provides are extremely limited, even in contrast to Georgian. This explains some of the nostalgia felt towards the Soviet Union in its former borderlands. Being ‘Soviet’ was an easy way to identify oneself. If you were, say, half-Kazakh and half-Polish, but ended up living in Ukraine after the Soviet Union’s collapse, where exactly were you from? I myself encounter this same difficulty when explaining my heritage to people: “Well, my Dad’s from St Petersburg, but we’re not really Russian – we’re Jewish and a quarter Ukrainian.” I’ve found it’s easier just to say ‘Russian’. Nonetheless, Panteleimon’s words struck a chord in me, so I decided to press him further: could the use of the Russian language as a ‘shield’ from Georgian reflect the political reality? And in what ways exactly has the situation with Abkhaz improved?

“In every sense… During my childhood, there were regions in Sukhumi where Abkhaz was practically never spoken, whereas today it is spoken everywhere. In the Soviet era, fewer than 200 ethnic Abkhazians lived in the Gulrypshskii region and in the Gagra region and the city of Ochamchire, they constituted less than 5% of the population. Today, even right by the border with Georgia in the Gali region, Abkhaz is the official language. All official activity is conducted in Abkhaz. The language’s reach has extended. Today, it’s very prestigious to be able to speak Abkhaz. There’s a fair number of people who occupy top positions in Abkhaz society due in no small part to their knowledge of the language. In any case, today no one physically or legally limits the use of the language. The use of the Russian language as an instrument of defence from Georgian influence reflected (reflected, but no more) the political situation.”

He even repeated the word ‘reflected’, (‘otrazhal’ in Russian), to me in English, to ensure that I did not misinterpret him. Evidently, he was trying to emphasise that linguistic developments in Abkhazia were products, rather than causes, of the way that politics in the region has unfolded. He then outlined what he saw as the way forward for Abkhazia after years of colonisation and warfare:

“Our tragic history from the middle of the 19th Century until the end of the 20th has shaped the political culture in Abkhazia for the worse, and it’s in this that the main problem lies. We now need to construct an agenda ourselves; not simply dodge the regular blows from Georgia but form our future for ourselves… we know what we don’t want, but we don’t know what we do want. We need to learn to form our own positive agenda, and not simply remain fixated on the traumas of the past. If Abkhazians are able to mobilise to form the foundations for positive goal-setting, then everything will work out for us. If the old elite doesn’t allow this, Abkhazia will suffer.”

Brother Panteleimon lays no claim to objectivity. In fact, he made a point of repeatedly reminding me that his is not an impartial voice – “Abkhazians cannot be objective in relation to Georgia.” However, his perspective provides an invaluable insight into broader Abkhaz thought. The dynamics at play don’t quite fit into classic notions regarding imperial power and nationality; it goes without saying that Russia was and continues to be an oppressive, imperialist state. But for Abkhazia, Georgia is the bigger threat. Perhaps this is due to Georgia’s insecurity regarding its own self-determination. In Russia they have no such qualms: leaving Abkhazians to their own devices is not an issue. However, If Abkhaz culture flourishes in Georgia, it is seen to be at the expense of Georgian culture. As Panteleimon says, the Abkhaz language has seen a resurgence over the last 25 years.

Elsewhere, these types of forces play out on an even larger scale. In Kazakhstan and Ukraine, governments are enacting a crackdown on Russian. Although it is spoken as a first language by many, the language is seen as a threat to national unity and identity. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Kazakh language has grown, yet this has not been accompanied by a corresponding decline in the use of Russian. In both Ukraine and Belarus, proficiency in Russian has in fact grown over the last twenty years, despite the proportion of ethnic Russians in their populations shrinking. In Belarus, according to the 2009 census, 40% of the Belarussian community considered Russian their native language, and 70% speak it at home. Whereas Belarussian is almost seen as a counterculture, Russian is associated with the political elite.

Russia’s political influence should not be conflated with the Russian language, the latter of which has not been linked to Russia alone for a long time. Eastern Europe’s breakaway territories, however, are tied very closely to the former. Moscow’s support for separatist forces is hardly altruistic. Firstly, and most significantly, that support comes from a desire to uphold a sphere of influence. By keeping these breakaway regions isolated and dependent on its aid, Russia maintains a firm grip on their internal politics and keeps a foothold in the post-Soviet world beyond its official borders. Secondly, it is a direct response to western recognition of Kosovo, which Russia perceives as illegal. Moscow’s outlook remains as paranoid as ever regarding the meddling of Western powers worldwide. Its foreign policy can only be understood when situated in this context.

Panteleimon and I also discussed our favourite writers, interesting case studies for the implications language has upon identity. This is particularly significant in the Russophone world where, in the absence of democracy and a free press, they have historically formed the loudest voice opposing the state. Fazil Iskander, arguably Abkhazia’s most renowned author, was an Abkhaz speaker himself, and focused much of his subject matter on his homeland. He spent much of his childhood in Abkhaz-speaking villages and spoke of himself as ‘the bard of Abkhazia’. But he wrote almost all his work in Russian. He was referred to, both by himself and others, as a ‘Russian writer’, and attended a Russian-language school in Sukhumi during his childhood.

The most famous writer in this vein is undoubtedly Nikolai Gogol, one of the founding fathers of Russian literature. Half-Polish and half-Ukrainian, he wrote in Russian about provincial life and folklore in Ukraine, where he had grown up. His conceptions of Russo-Ukrainian relations are still espoused by Putin today. Putin has repeated on many occasions that Russians and Ukrainians, along with Belarussians, are ‘one nation’. The historical names of the countries in Russian reflect this. Russia is (and remains) ‘Rossiya’, whilst Ukraine was ‘Malorossiya’, literally ‘Little Russia’, and Belarus was ‘Byelorossiya’, ‘White Russia’. At the start of the nineteenth Century, when people talked of ‘Russians’, they were referring to the natives of all three countries. Gogol saw himself as a Ukrainian, but this did not preclude him from considering himself a Russian, too.

As we move towards Ukraine we reach another breakaway state, Transdniestria. On the eastern bank of Moldova, it is inhabited by a mixture of Moldovans, Ukrainians, Romanians, Russians, and Russian-speaking Jews. The conflict which saw Transdniestria’s birth in 1992 was the culmination of various historical and political factors. It was fought on ethnic and linguistic delineations between Moldovans and the Russians and Ukrainians. The Slavic nationalities held a demographic majority in the territory east of the river Dniester, and while the Moldovans were discussing leaving the USSR and reuniting with Romania, they were conversely in favour of maintaining close ties to Russia and upholding Russian as the region’s principal language. Russian is now the official language of the government and education in the de facto independent region, so you can guess which side won. In the rest of Moldova, Russian does not even share the status of a co-official language and it has not been obligatory to teach it in schools since 2002.

I put my questions regarding Transdniestria to Denis, a local. He said that Transdniestrians “sincerely feel themselves to be a part of Russia and the Russian-speaking world.” He claims many would say that they are “mentally Russian.” His impression is that Transdniestrians see Russia as a “mother”, whilst Moldova is a “neighbour, and nothing more”. And when he says this, I do believe it – or at least his perception. He is not particularly political and even said that he couldn’t answer when I asked him what he termed a ‘political question’. But it would be hard not to think this: comical as it may sound, the buses which travel around Tiraspol, the region’s capital, all have ‘TOGETHER WITH RUSSIA IN THE FUTURE!’ plastered on them in Russian. There was even a controversial referendum held in 2006. 98% of the Transdniestrian population voted for potential future integration with Russia, and 97% against renouncing independence and reuniting with Moldova. There were many allegations of voters being coerced by activists, exclusion of ‘unreliable’ voters from the voting list, and others being allowed to vote multiple times.

I often find the coverage of Eastern Europe in the West disheartening. Vodka, Putin, communism, and brown bears crop up all too frequently. The result is the simultaneous romanticisation of what can often be a harsh reality, and the homogenisation of rich and complex cultures into something simplistic and vulgar. If you search ‘Transnistria’ on Google, for instance, the first article that appears describes it as ‘A Stuck-in-Time Soviet Country’, and on the face of things, it may seem so. But its residents cannot be lumped together, as is the case in any country. Denis, for instance, is an avid photographer and a huge fan of The Chainsmokers. These places are not ‘backward’; they are not frozen in time. From what I’d read, I’d expected to cross the bridge into Abkhazia by foot, or by horse and cart. But a taxi was easy to find.

As opposed to nationalism, I’ve been struck by the sadness locals tend to feel due to how the current situation limits their opportunities. After all, what use is a passport from somewhere that does not exist? One person I met has what I find to be a very depressing Instagram account filled with what they described as ‘things I find cool, and dreams for the future’: pictures of Paris, London, cars and watches. Brother Panteleimon does, admittedly, seem somewhat more nationalistic. However, we need to remember several things. Firstly, that out of the breakaway territories, Abkhazia is the most set on complete autonomy and independence; secondly, that he is an overtly political person; and thirdly, that I was pressing him on his views.

I recently attended a talk on these breakaway territories, where the speaker recalled seeing an ‘IKEA’ sign in Sukhumi; needless to say, following the sign did not direct you to IKEA, but rather to the second floor of an arbitrary shop. Yet it hints at something larger: a deep-seated desire for normality. In the same talk, the speaker said how he had walked in on an ‘English language week’ at Sukhumi University, where prior to his arrival, there had not been a single native English speaker. This reminded me of my own experiences, and the bafflement and awe I consistently provoked when I told people I was from the UK. I believe that rather than romanticising the negative aspects of eastern Europe and its breakaway territories, or conversely orientalising them, we should work to seek constructive solutions for those on the ground. I only shed the misconceptions I held when I saw these hinterlands for myself, and interacted with the people who actually lived there. Whilst not everyone will be able to visit Abkhazia and talk to Panteleimon, I hope that if western coverage of these territories improves, people may not fall into the same traps I once did.

[all quotations are translated from Russian]

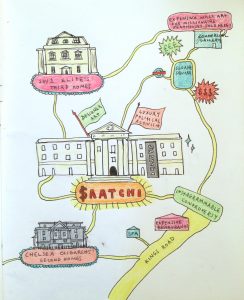

Words by Leo Gadaski. Art By Maia Webb-Hayward.