Art Riot: Post-Soviet Actionism at the Saatchi Gallery

by Kirsten Chapman | January 30, 2018

In September 1917, a month shy of the Bolshevik Revolution, T.S. Eliot wrote that “Europeans […] fail to note that there are many kinds of Russians, corresponding to the many kinds of their fellow countrymen, and that most of these kinds, similarly to the kinds of their fellow-countrymen, are stupid”. ‘Art-Riot: Post-Soviet Actionism’, currently showing at the Saatchi Gallery, is a show on protest art in post-Soviet Russia that illuminates how superficial Eliot’s statement was, exposing the British public to the struggles of artists and activists under the repressive post-Soviet state. Tangentially linked to the centenary of the revolution, it nevertheless states an aim to ‘trace parallels’ between the issues it raises. These comprise freedom of speech, the role of the artist in contemporary Russia, and “repression experienced after the rise of the communist state 100 years ago.” Yet, just as the exhibition seeks to fill in these gaps in its audience’s knowledge, it inadvertently raises questions of whether protest art can even be suitably displayed in a gallery.

The exhibition begins with Oleg Kulik, who the gallery insists on labeling as an ‘iconic figure’. His performances, in particular his sustained act as a dog over several years in the 1990s, are visceral enough even in reproduction to shake off this constrictive label. The decision to follow Kulik with Pyotr Pavlensky makes sense despite the jump of two decades; these are artists connected in how they make their bodies vulnerable to expose the fragilities of the state. Pavlensky frequently brutalises his own body in his performances; in Segregation he cut off a section of his earlobe from atop a psychiatric clinic to protest political abuses of psychiatry. The shock value of these two artists is high, however these sections transcend the commercial pull of such extreme actions. Surrounded by images of Pavlensky wrapped in a cocoon of barbed wire, or fixed rigid in Red Square, his scrotum nailed to the ground, the artist’s body is keenly figured as a site of activism.

As the exhibition turns to consider the multifaceted nature of Russian identity, it increasingly trades in symbols. Arsen Savadov’s Donbass-Chocolate series reads the painful contradictions of Soviet identity through the juxtaposition of the bodies of miners and delicate ballet tutus. The tutus are a loaded reference as ‘Swan Lake’ was broadcast across all Soviet Union television channels during the 1991 attempted coup against Gorbachev. Although tackling a very different aspect of Soviet identity, AES+F’s Islamic Project similarly utilises symbols to poke holes in a single encapsulation of Russian-ness. Iconic landmarks such as Big Ben and the Sagrada Família are overlaid with scenes from Muslim-majority countries; the Statue of Liberty wears a burqa. This visualisation of paranoid Islamophobia, done in response to the breakout of the Chechen War in 1996, uses symbols of identity to provoke and to question.

Yet in the presentation of Pussy Riot, the star attractions of this exhibition, symbolism devoid of much significant meaning dominates. The conflict between punk art and the commercial sphere is not a new issue – how radical were the Sex Pistols for accepting lucrative record deals? – but becomes particularly relevant in the presentation of this radical punk group. Videos of the group’s performances jostle among lengthy exposition and reproductions of their internationally-recognisable image: anonymous figures in bright dresses, leggings and balaclavas. Their presentation of anonymity – a gesture of radical inclusiveness in which anyone can become part of the movement – becomes iconography. Huge paintings of balaclava-clad faces line the wall, and footage of their 2012 performance in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour is replayed inside a vibrant mock cathedral. The effect is one of deification, trampling over the complexities of their message in a rush to elevate them. The exhibition becomes lost in the celebrity of its subject, to the extent that it fails to interrogate the complexities of the group themselves.

Despite some striking intellectual gnarls, much of the contemporary art on display is presented without serious comment. The trading of symbols in art on Siberian autonomy seems confused. Paintings by Damir Muratov repurpose the Union Jack and the Stars and Stripes to create the pieces ‘United Kingdom of Siberia’ and ‘United States of Siberia’, new flags for a now-autonomous country. How do we reconcile the fraught symbolism of these national emblems with the complexities of Siberian identity? In exposing a Western public to these diverse political conflicts within Russia, it’s a question that the exhibition needs to answer, though it is neither noted nor explored.

A piece of exposition on the Blue Noses Group, a collective who take inspiration from Russian holy fools, states that ‘For the same reasons that Charlie Hebdo enrages Islamist fundamentalists, however, Russian politicians try to suppress the Blue Noses again and again – they recognise that laughter is a potent weapon’. This is a striking simplification, one that clumps together repressive reactions to art without differentiating between the different power structures at play. Pieces by the Blue Noses Group in which the faces of world leaders are superimposed into naked bodies are similarly wide-ranging to the point of banality. Donald Trump, Assad, Putin and King Jong Un cavort together on a bed; the justification for this particular grouping, beyond a vague sense of ‘bad’ world leaders (equating Donald Trump to Assad is a disingenuous comparison), is overlooked.

The most interesting parts of the exhibition are the moments when the artists themselves are unfettered from this idolisation and speak on their own terms. An arresting moment in the section on Pavlensky is a dramatisation of one of his interrogations in stark shadows on a blank wall. Pavlensky frequently publishes transcripts of his numerous interrogations, and in this moment the exhibition surrenders itself to the artist’s unfiltered voice, translated into English to be directly accessible to the London audience. The exhibition also contains a film following Nadya Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, two members of Pussy Riot who worked with the gallery, as they travel around Russia to speak out on conditions for female prisoners. They are attacked in a fast food restaurant in Nizhny Novgorod, sprayed with syringes of green dye and assaulted by a group of young men. After drifting through the fake cathedral, people paused here and stayed. In both instances, the effect was palpable: the words of the activist-artists cutting through the exhibition’s unresolvable attempts to define them, with moments of powerful clarity.

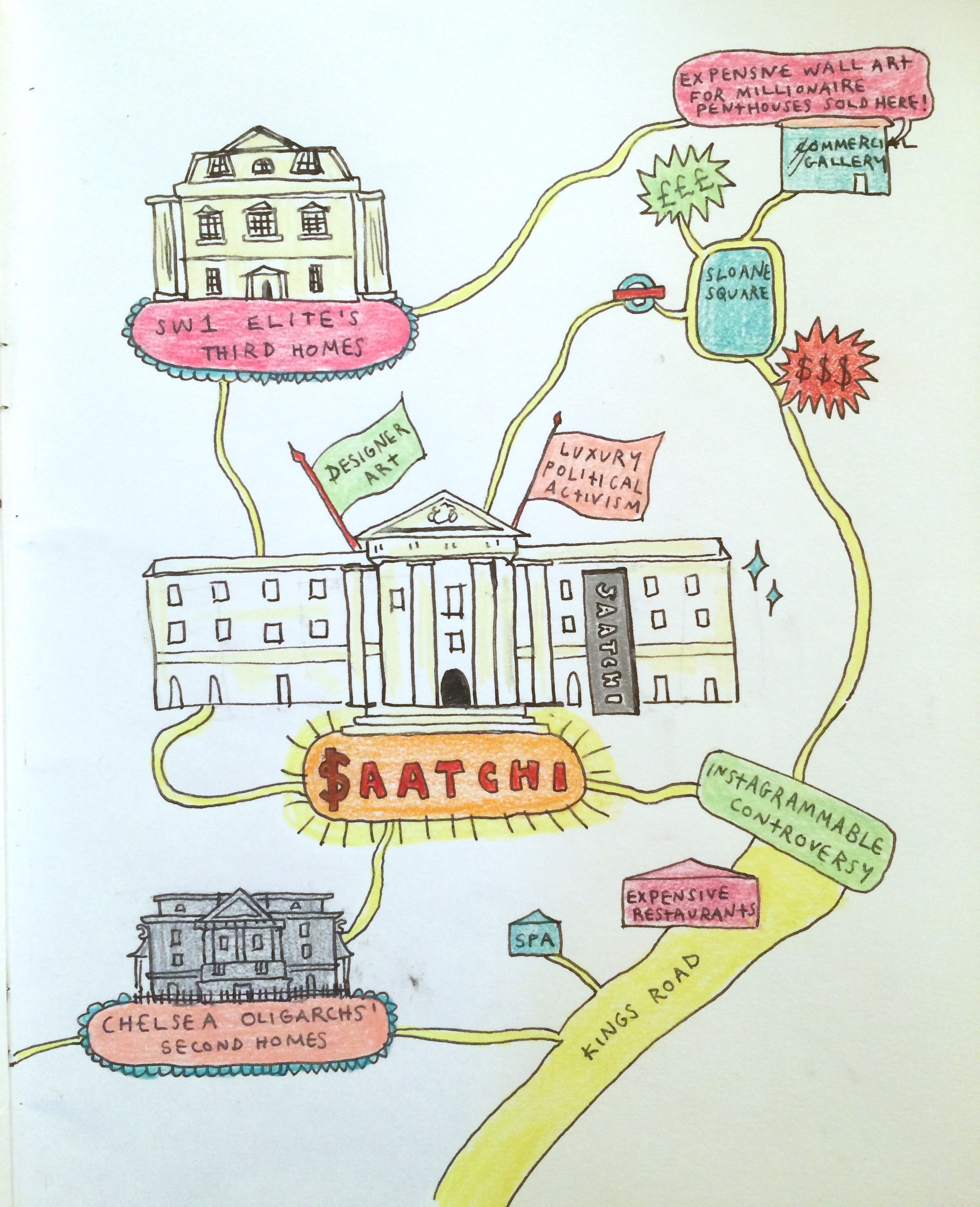

The Saatchi Gallery has a reputation for commercialization and ‘flashy’ exhibitions. This exhibition is the third in a series financed by the Tsukanov Family Foundation, the two previous shows described by the gallery itself as the ‘latest blockbuster shows’ of Russian art in London. The vexed position of the art in this context challenges the feasibility of this exhibition. The exhibition intended to provide a cohesive narrative of post-Soviet protest art, but unintentionally creates discord within itself, raising a multitude of questions about the relationship between art and activism that the exhibition did not intend to ask.

Artwork by: Georgiana Wilson